If all this

talk about collagen and texture isn’t gelling for you, do the following

experiment.

Take a few pieces of beef stew meat, and proceed as though you’re making beef stew.

Once your beef is in the slow cooker, set a timer for 30 minutes.

After 30 minutes, remove a few pieces of the beef. Use a probe thermometer on one to

record the internal temperature; it should register somewhere around 160–180°F /

71–82°C, although it’ll depend on your slow cooker. Stash the 30-minute sample in a

container in your fridge.

After six hours of stewing, repeat the procedure: remove a few pieces, verify that

the temperature is about the same, and stash the second batch in a second container in

the fridge. (You could heat up the 30-minute batch, but then we’d be changing more than

one variable: who’s to say that reheating doesn’t change something?)

Once both samples are cold, do a taste comparison. Got kids? Do a single-blind

experiment to remove the placebo effect: blindfold the kids and don’t let them know

which is which. Got a spouse and kids? Do a double-blind experiment to control for both

placebo effect and observer bias: have your significant other scoop the beef into the

containers and label them only “A” and “B,” not telling you which is which, and then go

ahead and administer the blindfold test to your kids.

4. 158°F / 70°C: Vegetable Starches Break Down

Whereas meat is predominately proteins and fats, plants are

composed primarily of carbohydrates such as cellulose, starch, and pectin. Unlike proteins

in meat, which are extremely sensitive to heat and can quickly turn into shoe leather if

cooked too hot, carbohydrates in plants are generally more forgiving when exposed to

higher temperatures. (This is probably why we have meat thermometers but not vegetable

thermometers.)

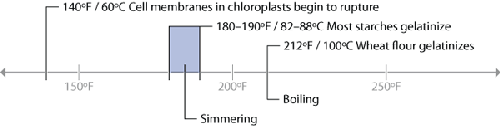

Temperatures related to plants and cooking.

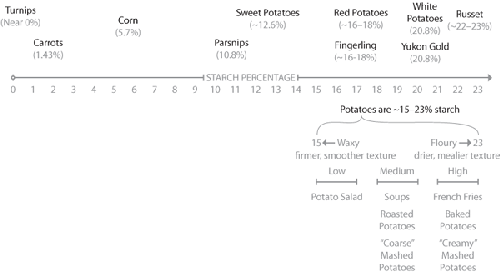

Cooking starchy vegetables such as potatoes causes the starches to gelatinize (i.e.,

swell up and become thicker). In their raw form, starches exist as semicrystalline

structures that your body can only partially digest. Cooking causes them to melt, absorb

water, swell, and convert to a form that can be more easily broken down by your digestive

system.

As with most other reactions in cooking, the point at which starch granules gelatinize

depends on more than just the single variable of temperature. The type of starch, the

length of time at temperature, the amount of moisture in the environment, and processing

conditions all impact the point at which any particular starch granule swells up and

gelatinizes.

Leafy green vegetables also undergo changes when cooked. Most noticeably, they lose

their green color as the membranes around the chloroplasts in the cells rupture. This same

rupturing and damage to the cell structure is what improves the texture of tougher greens

such as Swiss chard and kale.

For starchy plants (think potatoes), cook them so that they reach the temperature at

which they gelatinize, typically in the range of 180–190°F / 92–99°C. For green leafy

plants, sauté the leaves above 140°F / 60°C to break down the plant cell structure.

Note:

Cellulose—a.k.a. fiber—is completely indigestible in its raw form and gelatinizes at

such a high temperature, 608–626°F / 320–330°C, that we can ignore it while discussing

chemical reactions in cooking.

Starch levels in common vegetables.

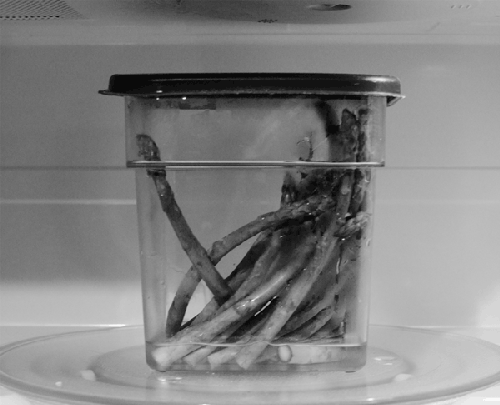

Microwave ovens make quick work of

cooking veggies. In a microwave-safe container, place asparagus stalks with the bottoms

trimmed or snapped off, and add a thin layer of water to the bottom. Put the lid on, but

leave it partially open so that steam has a place to escape. Microwave for two to four

minutes, checking for doneness partway through and adding more time as necessary.

Notes This technique cooks the food using two methods: radiant heat

(electromagnetic energy in the form of microwaves) and convection heat (from the

steam generated by heating the water in the container). The steam circulates

around the food, ensuring that any cold spots (areas missed by the microwave

radiation) get hot enough to both cook the food and kill any surface bacteria that

might be present. Try adding lemon juice, olive oil, or butter and sautéed, crushed

garlic to the asparagus.

|

Pectin is a polysaccharide found in

the cell walls of land plants that provides structure to the plant tissue. It breaks

down over time, which is why riper fruits become softer.

Cooking also breaks down pectin, and as a kitchen chemistry experiment, you can

capture the pectin from cooked fruits. It’s an easy way to see that some food additives

aren’t so industrial after all, at least not in their sources.

The pectin we use in cooking—primarily in jams and jellies, as a thickener—is

divided into two broad types: low- and high-methoxyl. High-methoxyl pectin requires a

high concentration of sugar in order to gel; low-methoxyl pectin will gel in the

presence of calcium. (The difference between the two types has to do with the number of

linkages in the molecular structure.)

If you’re making jams or jellies, using a low-methoxyl pectin (such as Pomona’s

Pectin) removes the variable of sugar concentration.

Making your own pectin is similar to making your own gelatin: start with a couple of

pounds of tissue, boil away, and then filter it out. Instead of animal bones, pectin

comes from the “bones” of cell walls in plant tissue.

Start with a few pounds of crisp apples. (The firmer the better! They don’t need to

be ripe.) Chop them into quarters and place the pieces in a stockpot. Cover with water

and simmer on low for several hours, stirring occasionally. (This is exactly the way

stock is made.) After several hours, you should have a slushy sauce. Filter this through

a strainer. The slimy liquid that you filter out is the pectin.

Using homemade pectin will be a bit trickier than Pomona’s Pectin, for two reasons.

First, it’s high-methoxyl pectin, so you’ll need to have a proper balance of sugar in

whatever you’re attempting to gel. And secondly, the concentration of pectin to water

will be unknown, so you will have to experiment some. Add a small quantity and test if

it gels; if not, add more. If the liquid pectin seems too thin, you can boil it down

further to create a more concentrated pectin.