Say

your Aunt Suzie sends you a jar of her famous (or is it infamous?) homemade quince jelly.

What to do with it? Someone suggests that you try it with Manchego cheese and crackers and,

sure enough, the combination is delicious. But why? One potential explanation can be found

in the history of the ingredients: they come from the same geographic region and its

corresponding cuisine.This method for thinking about flavor combinations is expressed in the idiom “if it

grows together, it goes together” and encompasses everything from a loose interpretation of

what the French call le goût de terroir (“taste of the earth”) to what

an American gourmand would term “regional cooking” for broad styles of cooking. In addition

to the limitation of ingredients based on what can be grown in any given area, regional

cooking also involves the culture and tradition of a region. Back to Aunt Suzie’s jelly:

Manchego cheese and quince jelly both have long histories in Spain, so the pairing is likely

rooted in history.

Given an ingredient, you can look at how that ingredient has been used historically in a

particular culture to find inspiration. (Think of it as historical crowdsourcing.) If

nothing else, limiting yourself to ingredients that would traditionally be used together can

help bring a certain uniformity to your dish, and serve as a fun challenge, too. And you can

extend this idea to wines to accompany your dishes, from the traditional (say, a French rosé

with Niçoise salad) to modern (Aussie Shiraz with barbeque).

The older the recipe, the harder it can be. One reason is

that language has changed. A lot. Take this example (also taken from Project Gutenberg) for

apple pie from The Forme of Cury, published around 1390 A.D.:

Tak gode Applys and gode Spycis and Figys and reysons and Perys and wan they

are wel brayed coloure wyth Safron wel and do yt in a cofyn and do yt forth to bake

well.

Almost as bad as a condensed tweet, this translates to: “Take good apples and good

spices and figs and raisins and pears and when they are well crushed, color well with

saffron and put in a coffin (pie pastry) and take it to bake.” (The “coffin”—little

basket—is an ancestor to modern-day pie pastry and would not have been edible at that point

in time.) Still, as a starting point for an experiment, the idea of making a mash of apples

and pears, some dried fruit, spices, and saffron suggests not just a recipe for pie filling,

but also a festive apple sauce for Thanksgiving.

Old recipes aren’t always so concise. Take Maistre Chiquart’s recipe for parma

torte in Du Fait de Cuisine, 1420 A.D. He starts with

“take 3 or 4 pigs, and if the affair should be larger than I can conceive, add another, and

from the pigs take off the heads and thighs, and...” He goes on for four pages, adding 300

pigeons and 200 chicks (“if the affair is at a time when you can’t find chicks, then 100

capons”); calling for both familiar spices like sage, parsley, and marjoram, and unfamiliar

ones such as hyssop and “grains of paradise”; and ending with instructions to place a pastry

version of the house coat of arms on top of the pie crust and decorate the top with a

“check-board pattern of gold leaf” (diamond-studded iPhone cases have

nothing on this guy).

Modernized version of parma torte, without the gold leaf, from

Du Fait de Cuisine, by Maistre Chiquart—France, 1420 A.D.

Needless to say, you’ll likely need to do some scaling and adaptation of older

recipes—again, part of the fun and experimentation! For parma tortes, I worked out my own

adaptation. I later found that Eleanor and Terence Scully’s Early French Cookery:

Sources, History, Original Recipes and Modern Adaptations (University of

Michigan Press) includes a nice adaptation.

Besides studying older recipes, you can look at traditional recipes from particular

regions to see how ingredients are normally combined. Different cultures have different

“flavor families,” ingredients that are thought of as having an affinity for one another.

Rosemary, garlic, and lemon are pleasing together—hence, traditional dishes like chicken

marinated in those ingredients. It can take time to build up a familiarity with flavor

families, but taking note of what ingredients show up together on menus, bottles of salad

dressings, or in seasoning packets is a good shortcut.

| |

Common ingredients

|

Served with...

|

|---|

|

Chinese

|

Bean sprouts, chilies, garlic, ginger, hoisin sauce, mushrooms, sesame oil,

soy, sugar

|

Rice

|

|

French

|

Butter, butter, and more butter, garlic, parsley, tarragon, wine

|

Bread

|

|

Greek

|

Garlic, lemon, oregano, parsley, pine nuts, yogurt

|

Orzo (pasta)

|

|

Indian

|

Cardamom seed, cayenne, coriander, cumin, ghee, ginger, mustard seed,

turmeric, yogurt

|

Rice or potatoes

|

|

Italian

|

Anchovies, balsamic vinegar, basil, citrus zest, fennel, garlic, lemon juice,

mint, oregano, red pepper flakes, rosemary

|

Risotto or pasta

|

|

Japanese

|

Ginger, mirin, mushrooms, scallions, soy

|

Rice

|

|

Latin American

|

Chilies, cilantro, citrus, cumin, ginger, lime, rum

|

Rice

|

|

Southeast Asian

|

Cayenne, coconut, fish sauce, kaffir lime leaves, lemon grass, lime, Thai

pepper

|

Rice or noodles

|

Common ingredients used in chicken dishes by a few common cuisines. (Note

that not all of these ingredients would be used simultaneously.)

The ingredients used to bring balance to a dish will vary by region. For example, the

Greeks use lemon juice in horta to moderate the bitterness of the dark

leafy greens like dandelion greens, mustard greens, and broccoli rabe, while the Italian

equivalent uses balsamic vinegar.

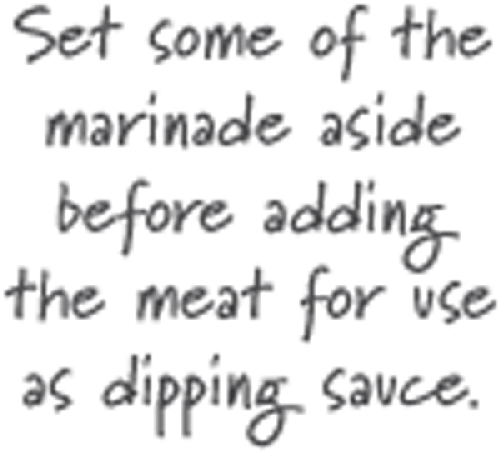

With even a short list of culturally specific ingredients as inspiration, you can create

simple marinades and dipping sauces without too much work. Pick a few ingredients, mix them

in a bowl, and toss in tofu or meat such as chicken tenderloins or steak. Allow the tofu or

meat to marinate in the fridge for anywhere from 30 minutes to a few hours, and then grill

away.

When creating your own marinade, if you’re not sure about the quantities, give it a

guess. This is a great way to build up that experiential memory of what works and what

doesn’t.

In a bowl, mix: ¼ cup (60g) yogurt 1 tablespoon (15g) lemon juice (about ½ lemon’s

worth) 1 teaspoon (2g) oregano ½ teaspoon (3g) salt Zest of 1 lemon, minced finely

|

In a bowl, mix: ¼ cup (70g) low-sodium soy sauce (regular soy sauce will

be too salty) 2 tablespoons (10g) minced ginger 3 tablespoons (20g) minced scallions (also known as green

onions), about 2 stalks 2 tablespoons (40g) honey

|

| |

Bitter

|

Salty

|

Sour

|

Sweet

|

Umami

|

Hot

|

|---|

|

Chinese

|

Chinese broccoli

Bitter melon

|

Soy sauce

Oyster sauce

|

Rice vinegar

Plum sauce (sweet and sour)

|

Plum sauce (sweet and sour)

Jujubes (small red dates)

Hoisin sauce

|

Dried mushrooms

Oyster sauce

|

Mustard

Szechwan peppers

Ginger root

|

|

French

|

Frisée

Radish

Endive

Olives

|

Olives

Capers

|

Red wine vinegar

Lemon juice

|

Sugar

|

Tomato

Mushrooms

|

Dijon mustard

Black, white, and green peppercorns

|

|

Greek

|

Dandelion greens

Mustard greens

Broccoli rabe

|

Feta cheese

|

Lemon

|

Honey

|

Tomato

|

Black pepper

Garlic

|

|

Indian

|

Asafetida

Fenugreek

Bitter melon

|

Kala namak (black salt, which is NaCl and Na2S)

|

Lemon

Lime

Amchur (ground dried green mangoes)

Tamarind

|

Sugar

Jaggery (unrefined palm sugar)

|

Tomato

|

Black pepper

Chilies, cayenne pepper

Black mustard seed

Garlic

Ginger

Cloves

|

|

Italian

|

Broccoli rabe

Olives

Artichoke

Radicchio

|

Prosciutto

Cheese (pecorino or parmigiano-reggiano)

Capers or anchovies (commonly packed in salt)

|

Balsamic vinegar

Lemon

|

Sugar

Caramelized veggies

Raisins / dried fruits

|

Tomato

Parmesan cheese

|

Garlic

Black pepper

Italian hot long chilies

Cherry peppers

|

|

Japanese

|

Tea

|

Soy sauce

Miso

Seaweed

|

Rice vinegar

|

Mirin

|

Shitake mushrooms

Miso

Dashi

|

Wasabi

Chiles

|

|

Latin American

|

Chocolate (unsweetened)

Beer

|

Cheeses

Olives

|

Tamarind

Lime

|

Sugar cane

|

Tomato

|

Jalapeño and other hot peppers

|

|

Southeast Asian

|

Dried tangerine peel

Pomelo (citrus fruit)

|

Fish sauce

Dried shrimp paste

|

Tamarind

Kaffir limes

|

Coconut milk

|

Fermented bean paste

|

Bird chili

Thai chili in sauces and pastes

|

Examples of ingredients used by different cultures to balance out flavors.

Use this chart as an inspiration to try out new combinations and take note of how the

various flavors change your perceptions.