Cooking “within season” means using only those

ingredients that have good, fresh flavor and are ripe. Restricting yourself to ingredients

that are in season in your region is a great way of creating constant challenges and

exposing yourself to new ingredients. And because in-season ingredients tend to be of higher

quality and pack more of a flavor punch, it’s that much easier to make the resulting dishes

taste good. Next time you’re at the grocery store, take note of what new fruits and

vegetables have arrived and what is in dwindling supply.Of course, not every ingredient in a dish is a “seasonal” ingredient. Cellar onions,

storage apples, and pantry goods such as rice, flour, and beans are year-round staples and

fair game. What is off-limits with this approach are those foods that are outside their

growing season for where you live. Put another way, don’t try making grilled peaches in

February. Even if you can get a peach in February, it won’t have the same flavor as a

mid-summer peach, so it will invariably taste flat. Even if those peaches shipped from Chile

taste okay, they won’t be as good as the local in-season peaches, because they have to be of

a variety that favors shipping durability and disease resistance over taste and texture.

(Unless you happen to live in Chile.)

One of the perks of using in-season ingredients, besides the quality, is that the

abundance of the in-season produce generally means lower prices, too, as the

supply-and-demand curves change. Grocery stores have to figure out how to sell all those

zucchinis when they come up for harvest, and running specials is one of the standard ways of

moving product. The same challenge applies even more if you’re growing your own fruits and

vegetables, because a home garden can produce an abundance over a short period of time. If

you figure out what to do with the 100 pounds of zucchini that all come ready in late

summer, I know plenty of people who would like to hear it!

Note:

In-season, local foods have the advantage of typically being fresher than their

conventional counterparts, which is especially important for flavor in highly perishable

foods such as heirloom tomatoes and fresh seafood. Local isn’t always better, though. For

example, if you live in a northern climate, you might find that produce such as radishes

from traditional farms located where it gets hotter might taste better.

First they say farm-raised salmon is better, then it’s

wild salmon. Or the blogs light up with posts about how many metric tons of greenhouse

gases or gallons of water are associated with producing an average cheeseburger. Then

there’s the whole “local food” movement wanting to help with reducing our collective

carbon footprint. What’s an environmentally conscious geek to do? It depends. How much are you willing to give up? Let’s start with the good news, with the greenest of the green: your veggies. Locally

grown veggies combined with a minimum of transportation and sold unpackaged are about as

good as you can get for the environment, and they’re about as good as you can get for

yourself. Look for a farmers’ market in the summer (or if you’re lucky enough to live in

California, year-round). Farmers’ markets are a great way to really understand where your

food is coming from. Plus, your local economy will thank you. You can also subscribe to a CSA (community-supported agriculture) share, where every

week or two you receive a box of local and seasonal produce. It’s a great way to challenge

yourself in the kitchen, because invariably something unfamiliar will show up in your CSA

share, or you’ll find yourself with 10 pounds of spinach and be looking for something new

to do with it. Regardless of anything else, your mother was right: eat your veggies. (On a

personal note unrelated to the environment, I believe the typical American diet doesn’t

include enough veggies. Eat more veggies! More!) In the other corner, there are red meats like corn-fed beef. It’s environmentally

expensive to produce: the cow has to eat, and if fed corn (instead of grass), the corn has

to be grown, harvested, and processed. All this results in a higher carbon footprint per

pound of slaughtered meat than that of smaller animals like chickens. Then there’s the

fuel expended in transportation, along with the environmental impact of the packaging. By

some estimates, producing a pound of red meat creates, on average, four times the

greenhouse-gas emissions as a pound of poultry or fish. Regardless of where you fall on the spectrum between local-shopping vegan and

delighting in a ginormous bacon-wrapped slab of corn-fed beef, limiting consumption in

general is the best method for helping the environment. Choose foods that have lower

impact on the environment, and be mindful of wasted food. See the caveat below, but

current data suggests the total impact on the environment of consuming fish is less than

the impact of eating chicken and turkey, which likewise is more sustainable than pork,

which is in turn better for the environment than beef. This isn’t to say all red meats are bad. If that steak you’re cutting into came from a

locally raised, grass-fed cow, she might actually be playing a positive role in the

environment by converting the energy stored in grass into fertilizer (i.e., manure) for

other organisms to use. See Michael Pollan’s classic The Omnivore’s

Dilemma (Penguin) for more on this topic, but as a general rule, the more

legs it has, the “less good” it is for the environment. (By this logic, centipedes are

pure evil...) By most analyses, cutting the amount of red meat you consume is the easiest way to

make a positive impact on the environment. One friend of mine follows the “no-buy” policy:

he happily eats it, but won’t buy it. I’ve heard of others

following variants of Mark Bittman’s “vegan before 6″ diet: limiting consumption of meats

during the day but pigging out at dinner. With respect to fish, whether farm raised or wild-caught is better depends upon the

species of fish, so there’s no good general rule. There are issues with both types: some

methods of farm fishing generate pollutants or allow fish to escape and commingle with

wild species, while wild-caught contributes to the depletion of the ocean’s stocks, and

the impact of a global collapse in the fisheries from over-fishing is a very real threat

to the food supply to hundreds of millions. The biggest contribution you can make—at least on the dinner plate—is to avoid

wild-caught seafood of species that are overfished. The Monterey Bay Aquarium runs a great

service called “Seafood WATCH” that provides a list of “best,” “okay,” and “avoid”

species, updated frequently and broken out by geographic region of the country. |

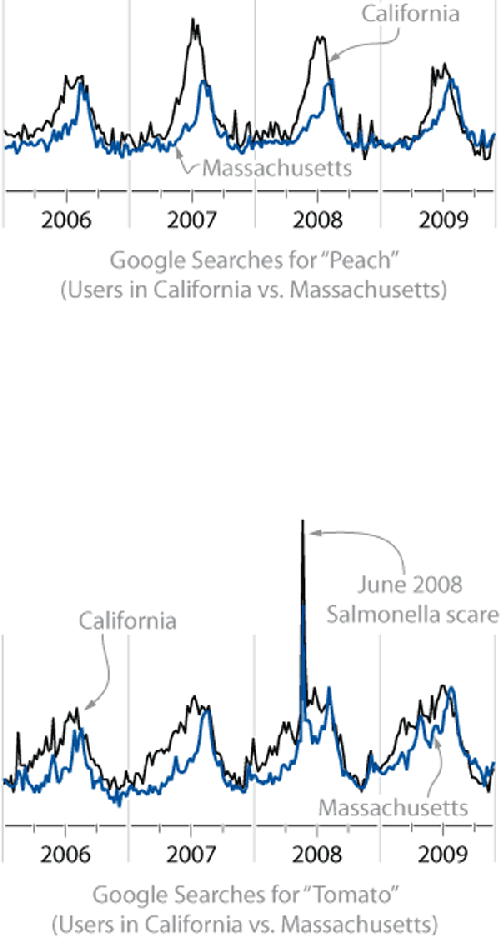

Data from Google Trends showing search volumes for the terms “peach”

(left) and “tomato” (right) for California users and Massachusetts users. The growing

season in Massachusetts starts later and is much shorter than in California. There’s a

tight correlation of this with Google’s search volumes for those

terms.

If it’s the dead of winter and there’s a foot of snow on the ground (incidentally,

not the best time to eat out at restaurants specializing in local,

organic fare), finding produce with “good flavor” can be a real challenge. You will have to

work harder to produce flavors on par with those in summer meals. Working with the seasons

means adapting the menu. There’s a reason why classic French winter dishes like cassoulet

(traditionally made with beans and slow-cooked meats, but that description does

not do this amazing dish justice—I make mine with duck confit, bacon,

sausage, and beans, then slow roast it overnight) and coq au vin (stewed

chicken in wine) use cellar vegetables such as onions, carrots, turnips, and potatoes and

slow, long-cooking simmers to tenderize tougher cuts of meat. I can’t imagine eating

cassoulet mid-summer, let alone venting the heat generated from keeping the oven on for that

long. Yet in the dead of winter, nothing’s better.

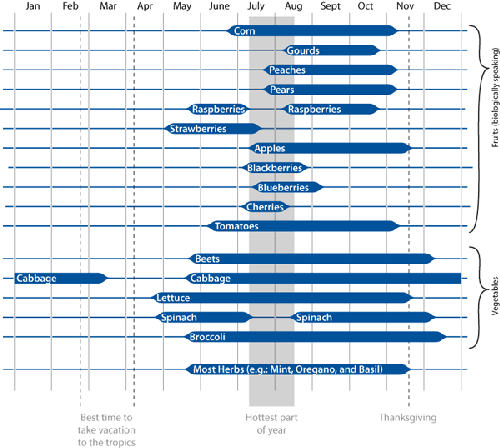

Seasonality chart for fruits and vegetables in New England. Fruits have a

shorter season than vegetables, and only a few vegetables survive past the first

frost. Some plants can’t tolerate the hottest part of the year; others do best during

those times. If you live in the Bay Area or New York, see

http://www.localfoodswheel.com

for a nifty “what’s in season” wheel chart.

Consider the following three soups: gazpacho, butternut squash, and white bean and

garlic. The ingredients used in gazpacho and butternut squash soup are seasonal, so they

tend to be made in the summer and autumn, respectively (of course, modern agricultural

practices have greatly extended the availability of seasonal ingredients, and your climate

might be more temperate than the sources of these traditions). White bean and garlic soup,

on the other hand,

uses pantry goods that can be had at any time of year. Thus, it is traditionally thought of

as a winter soup, because it’s one of the few dishes that can be made that time of

year.