With technology at their fingertips,

children today are often exposed to a barrage of sexualized images and

messages. But is it all too much too soon, asks Sarah Marinos.

Raunchy music videos, advertising that

pushes sexual boundaries and internet sites containing sexual images and

messages…

Some child health experts believe that

today’s children are too soon and too often exposed to sexual messages that

they are emotionally and psychologically unprepared for. Without key adults in

their life to serve as a reference point for these messages and images,

children may become confused and anxious about how to interpret them. In some

cases, researchers believe it is leading to increasing numbers of Australian

children engaging in problem sexual behavior.

“We are seeing kids as young as seven or

eight exposing themselves to other kids,” says Dr Joe Tucci, CEO of The

Australia Childhood Foundation. “There has to be a link between this sexual

behavior and the saturation in the community of sexual themes. Kids are trying

to work out what they see and what it means. It makes children unsettled and

they are trying to overcome that unsettled feeling.”

Play catch-up

“Society has become increasingly full of

sexualized imagery. This has created a wallpaper to children’s lives. Parents

feel there is no escape and no clear space where children can be children,”

says Reg Bailey, author of a 2011 independent UK review on the subject.

Maggie Hamilton, author of “What’s

Happening to Our Girls?” (Penguin, $26.95), believes that while children in Australia are certainly exposed to this sexual wallpaper, there is no “evil plot”. It’s

more that society and technology have shifted and parents are trying to get up

to speed with the changes.

“Parents need to get back to their sense of

place in a child’s life,” she says. “It’s not the pop culture, the friends and

the marketing campaigns that are important to children. It is belonging, love

and feeling supported and protected. Kids might be seemingly confident but it’s

a shield to protect them from a world they hind hard to cope with.

“Parents can help children be empowered and

smart and feel good about themselves and where they are heading. We need to use

our own experiences and keep connecting with them so they can find the role

they want to take in life.”

Messages and mediums

On average, Australian children watch

around two hours and 30 minutes of TV per day. This means they see about 30

advertisements each hour. Despite regulations governing advertising and program

content, Tucci says advertisers and program makers are sophisticated in

including subtle sexual messaging.

In a 2008 submission to a government

inquiry on child sexualisation, Tucci listed further examples, including the

launch of padded bras for girls as young as six, dolls dressed in lingerie and

leather for young girls, and an adolescent T-shirt range bearing slogans such

as “Mr Well-Hung” and “Miss Floozy”. He says this “normalizes” sexual themes to

children.

“The regulations are pretty weak and people

find loopholes. There have to be a lot of complaints before regulations take

action and many people don’t even know who they should complain to,” he says.

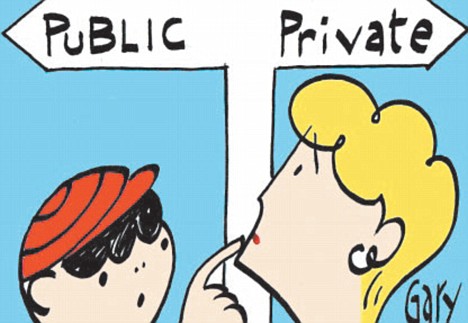

Public to private

The biggest concern today, however, is the

all-pervasive internet, with parental filters incapable of blocking out all

unsavory imagery for children.

“Before, we only really had public

communication, but technology has made things more private so it’s hard for

parents to keep up with what their kids are seeing,” says Tucci.

“The material that can be sent privately

now can be more sexually graphic and how do you explain some of this to a

child? And these mediums are normalizing this kind of content, so when you do

show this stuff on the internet you don’t get the same public outrage. It

desensitizes the community.”

Technology increases the potential for

inexperienced children to attract unwanted attention from sexual predators,

too. NetAlert, Australia’s internet safety advisory body, found almost 50 per

cent of children had been approached by a stranger on the internet.

“Every time a child goes online they run

the risk of viewing material that is unsuitable, frightening, distasteful or

illegal,” says Dr Michael Carr-Gregg, an adolescent psychologist and author of

“Real Wired Child: What parents need to know about kids” (Penguin, $19.95)