Taste is the set of sensations picked up by taste buds on the tongue (gustatory sense),

while smell is the set of sensations detected by the nose (olfactory sense). Even though

much of what we commonly think of as taste is really smell, our perception of flavor is

actually the result of the combination of these two senses.When you take a sip of a chocolate milkshake, the flavor you experience is a combination

of tastes picked up by your tongue (sweet, a tiny bit salty) combined with smells detected

by your nose (chocolate, dairy, a little vanilla, and maybe a hint of egg). Our brains trick

us into thinking that the sensation is a single input, located somewhere around the mouth,

but in reality the “sense” of flavor is happening up in the grey matter. In addition to the

taste and smell, our brains also factor in other data picked up by our mouths, such as

chemical irritation (think hot peppers) and texture, but this data plays only a minor role

in how we sense most flavors.

The most important variable for good flavor is the quality of the individual ingredients

you use. If the strawberries smell so amazing that they make your mouth water, they’re

probably good. If the fish looks appealing, doesn’t feel slimy, and smells “clean,” you’re

good to go. But if an avocado has no real smell and feels like it would be better suited for

a game of mini-football, there’s little chance that guacamole made from it will be

particularly appealing. And if the meat is a week past its use-by date and is home to

bacteria that have evolved to be smart enough to say, “well, hello there” when you open the

package? Definitely not good.

For a tomato-based dish to taste good, the tomatoes in it should taste and smell like

tomatoes. Just because the grocery store has a sign that reads “tomato” next to a pile of

red things that look like tomatoes but don’t smell like much doesn’t make them automatically

worthy of a place on your dinner plate. Though they just might not be ripe yet, more likely

than not they’re a variety that will never be truly flavorful. While serviceable in a

sandwich, many of the current mass-produced versions rarely bring the

pow or bam that is the hallmark of great

food.

Note:

This isn’t to say that mass-produced tomatoes can’t be flavorful. It’s just that the

most important variables for taste—primarily genetics, but also growing environment and

handling—haven’t been given very much attention in recent years.

It can be discouraging,

especially for someone new to cooking, to spend the time, money, and energy trying something

new only to have a disappointing outcome. Starting with good inputs gives you better odds of

getting a good output. You’re better off substituting something else that does pack a wallop

of flavor than using a low-quality version of a specified ingredient. If you’re shopping for

a green hardy leaf like kale but what you find looks like it has seen better days, keep

looking. Maybe the store has a pile of beautiful collard greens. Would that work? Give it a

try.

When it comes to detecting quality, your nose is a great tool. Fruits should smell

fragrant, fish should have little or no smell, and meats should smell mild and perhaps a

little gamey, but never bad. Smelling things isn’t foolproof—some cheeses are supposed to

smell like sweaty gym socks and there are some foodborne illness-causing bacteria that have

no odor—so you should still use common sense. Still, your sense of smell remains the best

way to find good flavor as well as root out whatever evil might be lurking inside.

1. Taste (Gustatory Sense)

Our tongues act as chemical detectors: receptor cells of the taste buds directly

interact with chemicals and ions broken down by our saliva from food. Once triggered, the

receptor cells send corresponding messages to our brains, which assemble the collective

set of signals and compile the data into a taste and its relative strength.

The basic tastes in western cuisine that Leucippus (or more likely one of his grad

students, Democritus) first described 2,400 years ago are salty, sweet, sour, and bitter.

Taste researchers are beginning to discover that Leucippus and Democritus described only

part of the picture, though. It turns out that our tongues are able to sense a few

secondary tastes as well. About a hundred years ago, Dr. Kikunae Ikeda identified a fifth

taste, which he named umami (sometimes called

savory in English) and described as having a “meaty” flavor. Umami

is triggered by receptors on the tongue sensing the amino acids glutamate and aspartate in

foods such as broths, hard aged cheeses like Parmesan, mushrooms, meats, and MSG. Recent

research suggests that we might also have additional receptors for chemicals such as fatty

acids and some metals.

Our taste buds also detect

and report oral irritation caused by chemicals such as ethyl alcohol and capsaicin, the

compound that makes hot peppers hot. Try tasting a small pinch of cinnamon and then some

cayenne pepper while keeping your nose plugged. Notice the sandy, flavorless sensation

caused by the cinnamon as compared to the sandy, flavorless, burning sensation caused by

the cayenne pepper. Capsaicin literally irritates the cells, which is why it’s used in

pepper sprays like Mace and in some antifouling paints used by the boating industry.

(Zebra mussels don’t like the cellular irritation either.)

Cellular irritation isn’t limited to the “hot” reaction generated by compounds like

capsaicin. Pungent reactions are triggered by other compounds, too. Szechuan (also known

as Sichuan) peppers, used in Asian cooking, and Melegueta peppers, used in Africa, cause a

mild pungent and numbing sensation. Another plant, Acmella oleracea,

produces Szechuan buttons, edible flowers that are high in the

compound spilanthol. Spilanthol causes a tingling reaction often compared to licking the

terminals on a nine-volt battery.

Spilanthol, the active ingredient in Szechuan buttons (which are also

known as sansho buttons or electric buttons), triggers receptors that cause a

numbing, tingling sensation. The “buttons” are actually the flowers of the Acmella

oleracea plant.

Regardless of how many types of receptors there are on the tongue or the mechanisms by

which taste sensations are triggered, the approach in cooking is the same: try to balance

the various tastes (e.g., not too salty, not too sweet).

Whether you find a set of flavors to be enjoyable or how you prefer tastes to be

balanced depends in large part on how your brain is wired and trained to respond to basic

tastes. If you’re like many geeks I know, you might have an affinity for coffee with lots

of sugar and milk or find a certain candy bar loaded with caramel and nuts and covered in

chocolate irresistible. But why are these things delicious? Because

our bodies find fats, sugars, and salts to be highly desirable, perhaps due to their

scarcity in the wild and the relative ease with which we can process them for their

nutrients.

Besides basic physiology, your cultural upbringing will affect where you find balance

in tastes. That is, what one culture finds ideally balanced won’t necessarily be the same

for another culture. Americans generally prefer foods to taste sweeter than our European

counterparts. Umami is a key taste in Japanese cuisine but has historically been given

less formal consideration in the European tradition (although this is starting to change).

Keep this in mind when you cook for others: what you find just right might be different

than someone else’s idea of perfection.

Identifying foods by flavor is harder than it

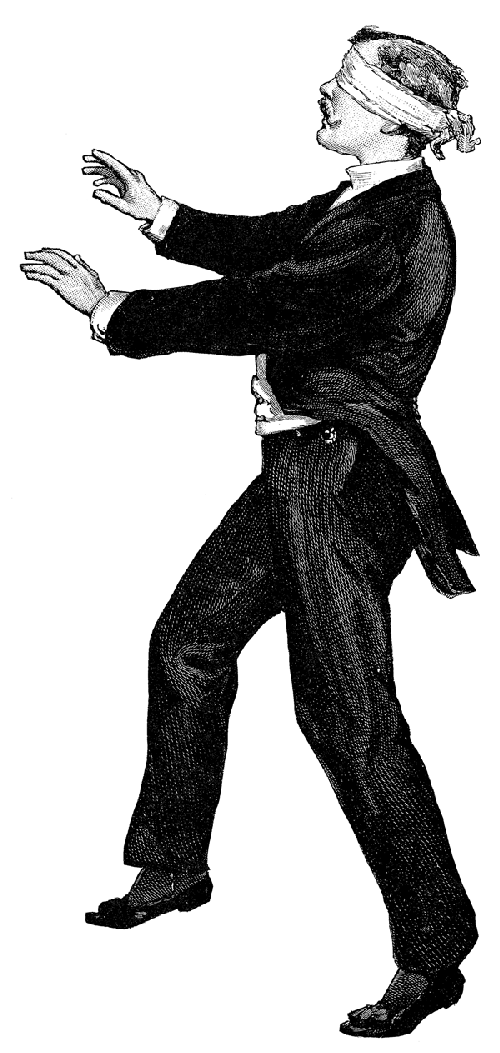

sounds. Here are two experiments you might enjoy. The first experiment uses both taste

and smell and requires a small amount of advance prep work. The second experiment uses

just smell and is easier to set up (but not quite as rewarding). Experiment #1: Taste and smell This exercise uses common foods from your grocery store, items that might not be

part of your day-to-day diet but are still generally familiar to many. Dice or purée the

items to remove any visual clues about their normal size and texture. You might be

surprised at the degree of difficulty in identifying some of them! It’s surprising to

discover how much “knowing” what a food item is—seeing the cilantro leaf or being told

it’s a hazelnut chocolate cupcake—allows us to sense the flavors and tastes we expect

from it. This exercise is best done in a group, because the experience can be surprising and

the resulting conversation really educational. I find that a group size of around six to

eight participants works best. Have tasters write down their guesses individually, and

then start a conversation about the experience when everyone’s finished. The person

preparing the exercise will, unfortunately, not be able to participate. In a set of small bowls, divide the following food items, setting with spoons or

toothpicks as appropriate: White turnip, cooked and diced Cooked polenta, diced (some stores carry packaged cooked

polenta that can be easily sliced) Hazelnuts ground to the size of coarse

sand Cilantro paste (look in the frozen food section; or buy

fresh cilantro and use a mortar and pestle to make a paste) Tamarind paste or tamarind concentrate Oreo cookies, ground (both cookie and filling; will

result in a black powder) Almond butter (or any nut butter other than peanut

butter) Caraway seeds Jicama root, diced Puréed blackberry

Notes If you’re setting this up for more than a few people, use ice cube

trays instead of small bowls so that you can put a tray down in the center of a

table with six to eight participants around each tray. Jicama root and tamarind paste are a bit obscure, but they serve as

fun challenges for tasters familiar with common flavors. If your local grocery

store doesn’t carry these, they can be found in almost any Asian grocery

store. Try to keep the diced items all of a consistent size, around ⅓″ or 1

cm.

Note: Hazelnuts or filberts? They’re actually different things—the outer husk of a

filbert is longer than that of a hazelnut—but either is fine.

Experiment #2:

Smell If you’d rather avoid food prep work, you can do a smell test instead. Place the

following items into paper cups, one per cup, and cover the cups with gauze or

cheesecloth to prevent peeking (you can use a rubber band around the perimeter to hold

the gauze in place; blindfolds work too for small groups): Almond extract Baby powder Chocolate chips Coffee beans Cologne or perfume (sprayed directly into the cup or

onto a tissue) Garlic, crushed Glass cleaner Grass, chopped up Lemon, sliced into wedges Maple syrup (real maple syrup, not

that “Pancake Syrup” stuff) Orange peels Soy sauce Tea leaves Vanilla extract Wood shavings (e.g., saw dust, pencil

shavings)

Label each cup with a number, and have test takers write down their guesses on a

sheet of paper. Notes You might find that some people are much better at detecting odors

than others. Just as with taste, any given smell can be detected at various

strengths. Some people are very sensitive to smells; others have a harder time

detecting odors (a condition known as hyposmia). Like

eyesight and hearing, our sense of smell begins to deteriorate sometime in our

thirties and starts to fall off faster once we reach our sixties. It’s a slow

decline, and unlike hearing and eyesight, is hard to notice as it changes, but the

loss does impact our enjoyment of food to some degree. If you are interested in taking a “real” smell test, researchers at

the University of Pennsylvania have developed a well-validated scratch-and-sniff

test called UPSIT that you can mail order. Search online for “University of

Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test.”

|

What you eat does leave a

taste in your mouth. Try the following experiment.

You’ll need sugar, a slice of lemon or some lemon juice, and a glass of water. Take

a sip of the water (tastes like, well...water). Suck on the slice of lemon, or if you’re

using lemon juice, take a spoonful and let it sit on your tongue. Take another swig of

water; it should taste sweet. Now, take a bit of sugar on a spoon and let it coat your

tongue for at least 10 seconds. If you try the water again now, you may find that it

tastes sour. Taste researchers call this phenomenon carryover and

adaptation.

When planning what to serve together, you should consider how the tastes in a group

of dishes and drinks will interact. When serving one course after another, the tastes

from the first course can linger, which is where a palate cleanser course comes in

during multicourse meals. A common traditional palate cleanser is a sparkling beverage

(carbonated water or sparkling wine), although some studies suggest crackers are more

effective. Maybe that bread basket on the table isn’t just about filling you up!