3. Sour

Sour tastes are caused by acids in foods. The sensation of sourness is detected by

part of the taste bud (ion channels) interacting with the hydrogen ions in the acids.

Quite literally, your sour taste buds are a primitive chemical pH tester. In cooking,

lemon juice and vinegar are commonly used to make dishes more sour, sometimes for effect

but more often to bring balance. When cooking, taste the food and think about the balance

of both saltiness and sourness, adding an ingredient such as vinegar to “brighten up” the

flavors.

Note:

In Latin American and Asian cuisines, tamarind paste is often used to adjust the

sourness of a dish.

From an evolutionary perspective, we appear to have evolved to taste sourness as one

method of determining spoilage, because a number of acids are produced by bacteria during

the breakdown of food. This isn’t to say that sourness in food is always due to bacterial

breakdown or that the fermentation caused by bacterial breakdown necessarily results in

bad food. Lemon juice is sour due to citric acid, and yogurt (pH of 3.8–4.2) acquires a

sour taste because of the lactic acid created by the bacteria breaking down the lactose in

the milk (pH of 6.0–6.8).

To get a better understanding of how bacteria make the taste of a food more sour, try

making your own yogurt using the recipe in Yogurt, tasting the liquid

before and after fermentation.

4. Sweet

We’re hardwired to like sweet foods—no surprise here. Sweet tastes signal quickly

digestible calories (and thus fast energy), which would have been more important in the

days when picking up the groceries also involved picking up a spear.

Our desire for sweetness changes over our lifespan. Researchers have found that our

preference for sweetness decreases as we mature. A child’s preference for sweet things is

biologically related to the physical process of bone growth. (Quick, kids, run and tell

your parents that your sweet tooth is

because of biology!) And the infamous sweet tooth isn’t unique to

American kids either; this finding holds up in other cultures.

Sugar is good at simultaneously promoting other flavors while masking sour and bitter

tastes. Take ginger, which has a strong, pungent, and slightly sour taste. With a bit of

sugar, it becomes enjoyable on its own; sugared and dipped in chocolate, it becomes

irresistible. Try making a simple ginger-flavored syrup (recipe at right).

In a pot, bring to a boil and then simmer on low heat: 2 cups (470g) water ½ cup (100g) sugar 6 oz (65g) ginger (raw), finely chopped or

minced

Simmer for 30 minutes, let cool, and then strain the mix into a bottle or container,

discarding the strained-out ginger pieces. Besides adding it to club soda for a simple ginger soda, try using this syrup on top

of pancakes or waffles or in mixed drinks (ginger mojitos!). You can also add a vanilla

bean, split lengthwise, to the mix while boiling to impart a richer flavor. And if the

idea of chocolate-covered candied ginger is still bouncing around your head. |

5. Umami (a.k.a. Savory)

Umami (a Japanese word that roughly translates to “savory”) generates a meaty,

broth-like, lip-smacking sensation typically triggered by some amino acids and nucleotides

(glutamate is the poster child; inosinate, guanylate, and aspartate are also not

uncommon). Glutamate is naturally present in a number of foods, especially mushrooms. To

an average American palate, umami is more subtle than the four primary tastes. It tends to

amplify our other senses of taste. For example, in dishes with salt, umami “brings out”

the salty taste, meaning that you can cut the amount of salt in a dish by adding

umami-tasting ingredients.

If you’re unable to imagine the taste of umami, make a simple broth by rehydrating a

tablespoon of dried shiitake mushrooms in 1 cup (240g) of boiling water. Let the mushrooms

steep for at least 15 minutes, and then remove them and save them for something else

(mmm, stir-fry). Taste the liquid; it will have a high glutamate

content dissolved out from the mushrooms. (If this is too much work for you, I suppose you

could just snag a container of MSG from your local Asian grocery store and dissolve a

small amount in a glass of water.)

Why we’ve evolved to have taste sensors for umami isn’t fully clear. Sweetness and

saltiness are both associated with positive attributes of food (quick energy in the case

of sweets and an element essential for regulating blood pressure in the case of

saltiness), while sourness and bitterness indicate potential danger. Perhaps umami is a

more subtle indicator of protein content, as a way of ensuring we ingest enough amino

acids to maintain muscle function. Regardless, umami is worth understanding for the

hedonistic value alone. MSG (monosodium glutamate) is to umami what sugar is to sweetness:

as a chemical, it’s relatively odorless (still full of taste!), but it triggers the umami

receptors on the tongue. MSG has gotten a bit of a bad rap in the United States, but so

have salt and sugar at various times.

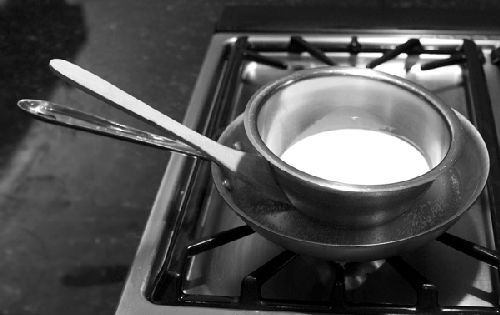

In a pan (or, preferably, a double-boiler),

gently heat: 1 cup (240ml) milk (any type other than

lactose-free)

Bring the milk up to 200°F / 93.3°C and hold at that temperature for 10 minutes

using a candy or IR thermometer. Do not boil, because that will affect the yogurt’s

flavor. After 10 minutes at temperature, transfer the milk to an open thermos, and wait

until it cools to 115°F / 46°C. Add and stir to combine: 1 tablespoon (14g) yogurt

Screw the lid onto the thermos and incubate for four hours. Transfer the liquid to a

storage container and put it in the fridge immediately. Notes The small addition of yogurt acts as a starter

because it contains the proper types of bacteria for “good” yogurt. Make

sure you use yogurt that states it has “active cultures.”

This recipe sterilizes the milk (pasteurized milk can still have a low

level of bacteria) and keeps the incubation period to four hours to reduce the

chance of growth of foodborne illness-related bacteria. Longer incubation times

lead to a stronger, more developed flavor. As with anything you eat, keep in mind

that if it tastes bad, smells off, or looks up at you and cracks a joke, you

probably shouldn’t eat it. (The inverse is, of course, not true: just because

something smells fine doesn’t mean it’s necessarily safe.) Try adding honey to the hot milk to take the sour edge off the

finished product (sweet helps mask sour). For “Greek-style” thick yogurt, place

the yogurt in a strainer over a bowl and let it drip-strain overnight in the

fridge.

|

There

are plenty of natural sources of glutamate. Many traditional Japanese dishes call for

dashi, a stock made from ingredients high in natural glutamate such

as kombu seaweed (2.2% glutamate by weight). Making dashi is super easy: in a pot, place 3

cups (700g) cold water and a 6″ / 15 cm strip of kombu (dried kelp), and let rest for 10

minutes. Bring to a boil slowly on low heat. Remove the kombu just before the water begins

to boil and add 10g of bonito flakes (flakes of dried and smoked bonito fish). Bring to a

boil, remove from heat, and strain out the bonito flakes. This liquid is dashi. To make

miso soup, add miso paste, diced tofu, and (optionally) sliced green onions, nori, or

wakame (an edible seaweed).

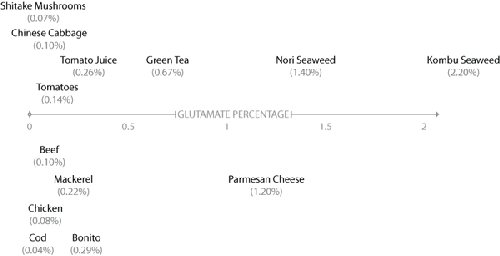

Glutamate occurs naturally in many other foods—for example, beef (0.1%) and cabbage

(0.1%). And if you’re like most geeks and pizza makes your mouth water, it might be

because of the glutamate in the ingredients: Parmesan cheese (1.2%), tomatoes (0.14%), and

mushrooms (0.07%).

Glutamate content of common ingredients.