6. Others

In addition to the primary sensations of taste, our taste buds also respond to oral

irritation brought about by hot peppers (typically from the chemical capsaicin), cooling

sensations (typically menthol from plants like peppermint), and carbonation. The reaction

to hot peppers is governed by a neurotransmitter called substance P

(P is for pain; go figure). In one of nature’s more subtle moves,

substance P can be depleted slowly and takes time—many days, possibly weeks—to replenish,

meaning that if you eat hot foods often, you literally build up a tolerance for hotter and

hotter foods as your ability to detect their presence goes down. Because of this, asking

someone else if a dish is spicy won’t always tell you if it’s safe to jump in. Carbonation

in soft drinks also irritates the taste buds, but in a different way that stimulates

the somatosensory

system. Carbonation also interacts with an enzyme (carbonic anhydrase 4) to trigger our

sour taste receptors, but for now it’s unclear as to why it doesn’t actually taste sour to

us.

Our mouths also capture data for a few chemical families present in some foods, along

with noticing texture and “mouthfeel.” Some of the sensations picked up by our mouths

include pungency, astringency, and cooling. Pungency is commonly described as being like

some strong, stinky French cheeses: a sharp, caustic quality. Astringency results when

certain compounds literally bind to taste receptors and causes a drying, puckering

reaction. Astringent foods include persimmon, some teas, and lower-quality pomegranate

juices (the bark and pulp are astringent). Cooling is the easiest to understand: the

chemical menthol, which occurs naturally in mint oils from plants such as peppermint,

triggers the same nerve pathways as cold. Menthol is commonly used in chewing gum and mint

candies.

Different cultures give different weights to some of the sensations listed here.

Ayurvedic practices on the Indian subcontinent include food recommendations as part of

their prescriptions, defining six types of taste: sweet, sour, salty, warm (like “hot” but

not the same kind of kick), bitter, and astringent. No umami, but two additional

variables: warm and astringent. Thai cooking also defines hot as a primary taste. For most

European cuisines, these additional variables are of lesser importance, possibly due to

genetic differences in taste receptors related to supertasting between Europeans and

Asians.

Your reaction to a particular taste is based in part on your prior experiences with

similar flavors. Have prior exposures been pleasant, or revolting? Taste aversions—a

strong dislike for a food, but not one based on an innate biological

preference—typically stem from prior bad experiences with food. Sometimes only a single

exposure that results in foodborne illness (and usually an unpleasant night near the

bathroom) is all that it takes for your brain to create the negative association. The food that triggers the illness is correctly identified only part of the time.

Typically, the blame is pinned on the most unfamiliar thing in a meal (this is known as

sauce béarnaise syndrome). Sometimes the illness isn’t even food-related, but a negative

association is still learned and becomes tied to the suspected culprit. This type of

conditioned taste aversion is known as “the Garcia Effect.” As further proof that we’re

at the mercy of our subconscious, consider this: even when we know we’ve misidentified

the cause of an illness (“It couldn’t be Tim’s mayonnaise salad, because everyone else

had it and they’re fine!”), an incorrectly associated food aversion will still

stick. One of the cleverest examinations of taste aversion was done by Carl Gustavson as a

grad student stuck at the ABD (all but dissertation) point of his PhD. Reasoning that

taste aversion could be artificially induced, he trained free-ranging coyotes to avoid

sheep by leaving (nonlethally) poisoned chunks of lamb around for the coyotes to eat.

They soon learned that the meat made them ill, and thus “learned” to avoid the sheep. I

don’t recommend this method for kicking a junk food habit or keeping your coworkers from

stealing unmarked food from the company fridge, as tempting as it might be. |

7. Combinations of Tastes and Smells

Most dishes involve a

combination of ingredients that contain at least two different primary tastes, because the

combination brings balance and adds depth and complexity. Whether the dish is a French

classic or a simple item of produce, the taste will be simple (“one note”) unless it’s

paired with at least one other.

To alter the flavor of fresh fruit, you can sprinkle it with sugar (try this on

strawberries) or salt (on grapefruit), wet it with lime juice (papaya, watermelon, peaches

with honey), or combine it with an ingredient from another taste family (sweet watermelon

and salty feta cheese). If you can find fresh papaya, try slicing it and sprinkling a bit

of cayenne pepper and salt on top of the pieces for a salty/sweet/hot combination. Try

replacing the papaya with other tropical fruits and the cayenne pepper with other hot

items. Guava and chili pepper? Mango salad with jalapeños and cilantro? Strawberries and

black pepper?

Note:

Black pepper has no capsaicin (the chemical that gives cayenne pepper and jalapeños

their heat) but is still pungent due to another chemical, piperine.

For another twist, try mixing foods high in fats with hot ingredients. They should

pair well with ingredients that contain capsaicin, because capsaicin is fat soluble.

Experiment with avocado and sriracha sauce, commonly known as rooster

sauce for the drawing on the bottle of one popular brand.

Note:

Rooster sauce (sriracha sauce—Thai hot sauce), it has been said, can improve the

taste of any dorm food, but beware, it’s spicy. As one friend

quipped to me, it’ll hit you like a freight train and then leave like a freight

train.

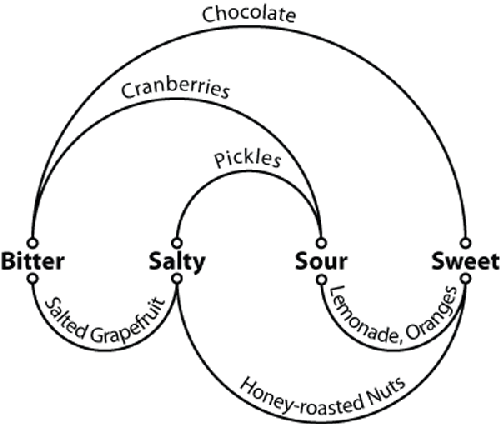

For you visual thinkers, here’s a diagram of the combinations of the

four basic flavors, with a few foods labeled for each combination. Ask yourself:

what other foods have these combinations? When cooking, think about which tastes

your dish emphasizes and in which direction you want it to go.

Many

foods are combinations of three or more primary tastes. Ketchup, for example, is

surprisingly complex, with tastes of umami (tomatoes), sourness (vinegar), sweetness

(sugar), and saltiness (salt).

Taste combinations are equally important in drinks. The hallmark of a well-mixed

cocktail is the balance between bitter (bitters) and sweet (sugar). Likewise, unless

you’ve learned to enjoy bitterness, coffee and tea (slightly bitter) are commonly combined

with sweeteners (milk, sugar, honey) or acidifiers (lemon juice, orange juice) to balance

out the tastes.

In some cases, the combination of different primary tastes is achieved by serving two

separate components together, pairing one dish with a second on the basis that the two

will complement each other. In Indian food, for example, the salty sweetness of a yogurt

lassi balances out the spicy hotness of curries. Consider the following combinations of

primary flavors. With the exception of bitter/salty, every pair of primary tastes is a

common combination.

|

Combination

|

Single-ingredient example

|

Combination example

|

|---|

|

Salty + sour

|

Pickles

Preserved lemon peel

|

Salad dressings

|

|

Salty + sweet

|

Seaweed (slightly sweet via mannitol)

|

Watermelon and feta cheese

Banana with sharp cheddar cheese

Cantaloupe and prosciutto

Chocolate-covered pretzels

|

|

Sour + sweet

|

Oranges

|

Lemon juice and sugar (e.g., lemonade)

Grilled corn with lime juice

|

|

Bitter + sour

|

Cranberries

Grapefruit (sour via citric acid; bitter via naringin)

|

Negroni (cocktail with gin, vermouth, Campari)

|

|

Bitter + sweet

|

Bitter parsley

Granny Smith apples

|

Bittersweet chocolate

Coffee/tea with sugar/honey

|

|

Bitter + salty

|

(N/A)

|

Sautéed kale with salt

Mustard greens with bacon

|

If it’s summertime and you’re able

to get good watermelon, try this simple salad to experience the contrast in flavors

between the salt in feta cheese and the sweetness of watermelon.

In a bowl, toss to coat:

2 cups (300g) watermelon, cubed or

scooped

½ cup (120g) feta cheese, cut into small

pieces

¼ cup (40g) red onion, sliced super thin, soaked and

drained

1 tablespoon (14g) olive oil (extra virgin because it

imparts flavor)

½ teaspoon (3g) balsamic vinegar

Notes

Try using a teaspoon or two of lime juice, instead of vinegar, as the

source of acidity. Alternatively, play with the tastes by adding black olives

(salty), mint leaves (cooling), or red pepper flakes (hot), thinking about how

each variation pushes the tastes in different directions.

There is some evidence that suggests our taste receptors can interact

with the capsaicin in hot peppers (for you bio geeks, via TRPM5) and possibly

menthol in mint (via TRPM8), but these interactions are not yet well understood in

the science domain, let alone the culinary world.

Always soak onions that will be served raw. When cut, an enzyme

(allinase) reacts with sulfoxides from the onion’s cells to produce sulfenic acid,

which stabilizes into a sulfuric gas (syn-propanethial-S-oxide) that can react

with water to produce sulfuric acid. This is why we cry when cutting onions: the

sulfuric gas interacts with the water in our eyes (the lacrimal fluid) to generate

sulfuric acid, which triggers our eyes to tear up to flush the sulfuric acid.

Because sulfides are water soluble, soaking the cut onions removes most of the

undesirable odors. You can soak them in water, or try vinegar to impart a bit of

additional flavor. Also, cutting onions in a wet environment provides liquid for

the sulfur compounds to dissolve into. Try pulling off the onion skin under water

and then cutting with a wet blade on a rinsed-but-not-dried cutting board. Another

method to reduce tearing is to chill the onion, because this makes the cell

structures firmer and reduces the amount of intra-cellular fluid available for the

allinases to react with.

If you’re lazy, skip cubing the watermelon and feta and instead serve

a slice of watermelon alongside a slice of feta, and alternate back and forth. You

can also make appetizers by skewering a cube of watermelon and a cube of feta with

a toothpick.

Dicing a watermelon is easier and faster than using a melon baller.

Using a knife, make a series of parallel slices in one direction, and then repeat

for the other two axes.