2. How to Prevent Foodborne Illness Caused by Parasites

Not long ago, I overheard the fishmonger at

one of my local grocery stores (which shall remain nameless to protect the guilty) tell a

customer that it was okay to use the salmon he was selling for making sushi. Given that

the fish wasn’t labeled as “previously frozen” and that it was in direct contact with

other fish in the case, there wasn’t any real guarantee that it was free from harmful

parasites or bacteria, two of the biggest concerns that consumers need to manage for food

safety. What’s a shopper to do in response to the disappearance of the true

fishmonger?

For one, start by understanding where the risks actually are. Not all fish and meats

share the same set of risks for foodborne pathogens. Salmonella, for example, tends to

show up in land animals and improperly handled vegetables, while bacteria such as

Vibrio vulnificus show up in fish that are exposed to the brackish

waters of tidal estuaries, such as salmon. Deep-water fish, such as tuna, are of less

concern. Because of these differences, you should consider the source of your ingredients

when thinking about food safety, focusing on the issues that are present in the particular

food at hand.

With uncooked and undercooked fish, one concern is parasites. Parasites are to fish as

bugs are to veggies: really common (if you’ve eaten fish, you’ve eaten worms). But on the

plus side, most parasites in seafood don’t infect humans. However, there are those that

do, Anisakis simplex and tapeworms (cestodes)

being the two parasites of general concern. A. simplex will give you

abdominal pains, will possibly cause you to vomit and generally feel like crap, and will

possibly take your doc a while to figure out. It’s not appendicitis, Crohn’s disease, nor

a gastric ulcer, and with only around 10 cases diagnosed per year in the United States,

chances are your doc won’t have encountered it before. On the plus side, humans are a

dead-end host for A. simplex. The bacteria will die after about 10

days, at which point you’ll go back to feeling normal. (Unless you have an extreme

infection, in which case, it’s off to surgery to remove ’em.) That leaves tapeworms as the

major parasitic concern in fish.

For cooked dishes—internal temperature of 140°F / 60°C—there is little risk from these

parasites directly. Cooking the fish also cooks the parasite, and while the thought of

eating a worm might be unappetizing, if it’s dead there’s little to worry about other than

the mental factor. (Just think of it as extra protein.)

Of course, raw and undercooked seafood is another matter entirely. Cod, halibut,

salmon? Fish cooked rare or medium rare? Ceviche, sashimi, cold-smoked fish? All potential

hosts for roundworm, tapeworms, and flukes. Fortunately, like most animals, few parasites

can survive freezing.

Note:

Some parasites do survive freezing.

Trichomonas—parasitic microorganisms that infect vertebrates—can

survive temperatures as cold as liquid nitrogen. Yikes!

For the FDA to consider raw or undercooked fish safe to eat, it must be frozen for a

period of time to kill any parasites that might be present:

FDA 2005 Food Code, Section 3-402.11: “[B]efore service or sale in

ready-to-eat form, raw, raw-marinated, partially cooked, or marinated-partially cooked

fish shall be: (1) Frozen and stored at a temperature of –20°C (–4°F) or below for a

minimum of 168 hours (7 days) in a freezer; [or] (2) Frozen at –35°C (–31°F) or below

until solid and stored at –35°C (–31°F) or below for a minimum of 15

hours...”

The second concern with undercooked fish is bacteria. While freezing kills parasites,

it does not kill bacteria; it just puts them “on ice.” Researchers store bacterial samples

at –94°F / –70°C to preserve them for future study, so even super-chilling food does not

destroy bacteria. Luckily, most bacteria in fish can be traced to surface contamination

due to improper handling—that is, cross-contamination from surfaces previously exposed to

contaminated items.

Note:

Don’t put cooked fish or meat on the same plate as the raw food! In addition to

being potentially dangerous, that’s just gross.

If your grocery store sells both raw and “sashimi-grade” fish, the difference between

the two will be in the handling and care related to the chances of surface contamination,

and in most cases the sashimi-grade fish should have been previously frozen. The FDA

doesn’t actually define what “sashimi grade” or “sushi grade” means, but it does

explicitly state that fish not intended to be completely cooked before serving must be

frozen before being served.

If you don’t have access to a good fish market or find the frozen fish available at

your local grocery store unappealing, and you plan on serving undercooked fish, you can

kill any parasites present in the fish by freezing: check that your freezer is at least as

cold as –4°F / –20°C, and follow the FDA rule of keeping the fish frozen for a week. If

you happen to have a supply of liquid nitrogen around—you know, just by chance—you can

also flash-freeze the fish, which should result in better texture and cut the hold time

down to less than a day.

Luckily for oyster lovers, the FDA excludes molluscan shellfish, as well as some types

of tuna and some farm-raised fish (those that are fed only food pellets that wouldn’t

contain live parasites) from the freezing requirement.

Is there a tension between safety and quality in cooking,

and if so, are there methods to achieve both? Safety and quality are two very different things. Quality is something that people

love talking about, whether it’s wine, or organic food, or how it was grown, and people

can talk themselves to death about all that. My job is to make sure they don’t

barf.

For somebody cooking at home, it’s easy for them to see a

difference in quality. It’s very hard for them to see a difference in safety until

they get sick, I imagine? There are tremendous nutritional benefits to having a year-round supply of fresh

fruits and vegetables. At the same time, the diet rich in fruits and vegetables is the

leading cause of food-borne illness in North America because they’re fresh, and anything

that touches them has the potential to contaminate. So how do you balance the potential

for risk against the potential benefits? Be aware of the risks and put in place safety

programs, beginning on the farm. If you look at cancer trends in the 1920s, the most predominant cancers were stomach

cancers. All everyone ate during the winter were pickles and vinegar and salt. Now

that’s almost completely eradicated because of fresh food. But now you have to prevent

contamination from the farm to the kitchen, because more food is eaten fresh. There are

tradeoffs in all of these things. In preparing hamburger and chicken, there is an issue

with cooking it thoroughly and validating that with a thermometer, but most of the risk

is actually associated with cross-contamination. Potatoes are grown in dirt, and birds

crap all over them, and bird crap is loaded with salmonella and campylobacter. When you

bring a potato into a kitchen or a food service operation, it’s just loaded with

bacteria that get all over the place. What’s the normal time between ingestion and

symptoms? It’s around one to two days for salmonella and E. coli. For

things like listeria, it can be up to two months. Hepatitis A is a month. You probably

can’t remember what you had yesterday or the day before, so how can you remember what

you ate a month ago? The fact that any outbreak actually gets tracked to the source I

find miraculous. In the past, if a hundred people went to a wedding or a funeral, they

all had the same meal. They all showed up at emergency two days later, and they would

have a common menu that investigators would look at to piece it together. Nowadays,

through DNA fingerprinting, it’s easier. If a person in Tennessee and a person in

Michigan and a person in New York have gotten sick from something, they take samples and

check against DNA fingerprints. There are computers working 24/7 along with humans

looking to make these matches. And they can say these people from all across the

country, they actually have the same bug, so they ate the same food. Think of spinach contamination in 2006. There were 200 people sick, but it was all

across the country. How did they put those together? Because they had the same DNA

fingerprint and they were able to find the same DNA fingerprint in E.

coli in a bag of spinach from someone’s kitchen. Then they were able to

find the same DNA fingerprint from a cow next to the spinach farm. It was one of the best cases with the most

conclusive evidence. Normally, you don’t have that much evidence. What to do about it isn’t very clear-cut, but when you look at most outbreaks,

they’re usually not acts of God. They’re usually such gross violations of sanitation

that you wonder why people didn’t get sicker earlier. With a lot of fresh produce

outbreaks, the irrigation water has either human or animal waste in it, and they’re

using that water to grow crops. These bugs exist naturally. We can take some regulatory

precautions, but what are we going to do, kill all the birds? But we can minimize the

impact. When farmers harvest crops, they can wash them in a chlorinated water system that

will reduce the bacterial loads. We know that cows and pigs and other animals carry

these bacteria and they’re going to get contaminated during slaughter. So we take other

steps to reduce the risk as much as possible, because by the time you get it home and go

to make those hamburgers, we know you’re going to make mistakes. I’ve got a PhD, and I’m

going to make mistakes. I want the number of bacteria as low as possible so that I don’t

make my one-year-old sick. Is there a particular count of bacteria that is required to

overwhelm the system? It depends on the microorganism. With something like salmonella or campylobacter, we

don’t know the proper dose response curves. We work backward when there is an outbreak.

If it’s something like a frozen food, where they might have a good sample because it’s

in someone’s freezer, we can find out more. With something like salmonella or

campylobacter, it looks like you need a million cells to trigger an infection. With

something like E. coli O157, you need about five. You have to take into account the lethality of the bug. For 10% of the victims,

E. coli O157 is going to blow out their kidneys and some are

going to die. With listeria, 30% are going to die. Salmonella and campylobacter tend not

to kill, but it’s not fun. So all of these things factor into it. A pregnant woman is 20

times more susceptible to listeria. That’s why they are warned to not eat deli meat,

smoked salmon, and refrigerated, ready-to-eat foods. Listeria grows in the refrigerator

and they’re 20 times more susceptible and it can kill their babies. Most people don’t

know that either. Are there any particular major messages that you would want

to get to consumers about food safety? It’s no different than anything else, like drunk driving or whatever other campaign:

be careful. The main message about food in our culture today is dominated by food

pornography. Turn on the TV and there are endless cooking shows, and all these people

going on about all these foods. None of that has anything to do with safety. You go to

the supermarket today, you can buy 40 different kinds of milk and 100 different kinds of

vegetables grown in different ways, but none of it says it’s E.

coli–free. Retailers are very reluctant to market on food safety, because

then people will think, “Oh my god, all food is dangerous!” All they have to do is read

a newspaper, and they’ll know that food is dangerous. A lot of the guidelines I see talk about the danger zone of

40–140°F / 4–60°C. A lot of those guidelines are just complete nonsense. The danger zone is nice and

it’s important not to leave food in the danger zone, but at the same time it doesn’t

really get into any details. People learn by telling stories. Just telling people “Don’t

do this with your food” doesn’t work; they say, “Yeah, okay, why?” I can tell you lots

of stories of why or why not. The guidelines aren’t changing what people do and that’s

why we do research on human behavior, how to actually get people to do what they’re

supposed to do. As Jon Stewart said in 2002, if you think those signs in the bathrooms

(“Employees must wash hands”) are keeping the piss out of your food, you’re wrong! What

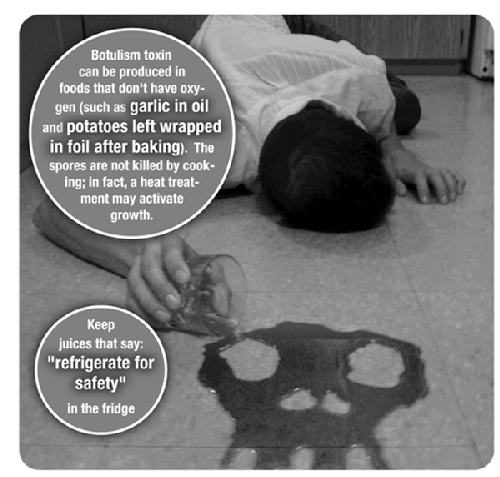

we want to do is come up with signs that work. I’m wondering what your signs look like? We have some good ones! Our favorite picture is the skull in the bed of lettuce! The

dead person from carrot juice is pretty good, too.

|

The safest way of preventing bacterial and

parasitic infections from seafood and meats is with proper cooking. The USDA recommends

cooking fish to a minimum internal temperature of 145°F / 63°C, ground beef to a minimum

internal temperature of 160°F / 71°C, and poultry to 165°F / 74°C.

If you enjoy your fish cooked only to a rare point or even raw in the middle and

you’re concerned about parasites, give frozen fish a chance. I’ve found distinct

differences in the quality of frozen fish. Some stores sell frozen product that’s

downright bad—mushy, bland, uninspiring—but this isn’t because the

fish was frozen. Some of the best sushi chefs in Japan are finding that quick-frozen

tuna is exceptionally good. Frozen at sea right after it’s caught (in a slurry of liquid

nitrogen and dry ice), the tuna doesn’t have much time to break down and so maintains

its quality during transportation.

One last comment on keeping yourself safe in the kitchen: the biggest issue isn’t

contaminated food from the store, but cross-contamination while preparing it at home.

Avoid cross-contamination by washing your hands often, especially both before and after

working with raw meat. Use hot water and soap, and wash for a good 20 seconds.