1. Bare Minimum Equipment

Here’s the equipment that you’ll need at a bare minimum.

1.1. Knives

Knife blades made of steel are manufactured in one of two ways: forging or stamping.

Forged blades tend to be heavier and “drag” through cuts better

due to the additional material present in the blade. Stamped blades

are lighter and, because of the harder alloys used, hold an edge longer. Which type of

knife is better is highly subjective and prone to starting flame wars (or is that flambé

wars?), and with some specialty sashimi knives listing for upward of $1,000, there are

plenty of options and rationales to go around.

Some people like a lighter knife, while others prefer something with more heft.

Personally, I’m perfectly happy with a stamped knife (currently, Dexter-Russell’s V-Lo

series) for most day-to-day work, although I do have a nice forged knife that I use for

slicing cooked meats.

Chef’s knife. If I could take only one tool to a

desert island, it would be my chef’s knife. What size and style of chef’s knife is best

for you is a matter of preference. A typical chef’s knife is around 8″ / 20 cm to 9″ /

23 cm long and has a slightly curved blade, which allows for rocking the blade for

chopping and pulling the blade through foods. If you have a large work surface, try a

10″ / 25 cm or larger knife. Or, if you have smaller hands, you might want to look at a

Santoku-style knife, a Japanese-inspired design that has an almost flat blade and a

thinner cross-section. Keep in mind, though, that Santoku knives are best suited for

straight up-and-down cutting motions, not rocking chopping motions or pulling through

foods.

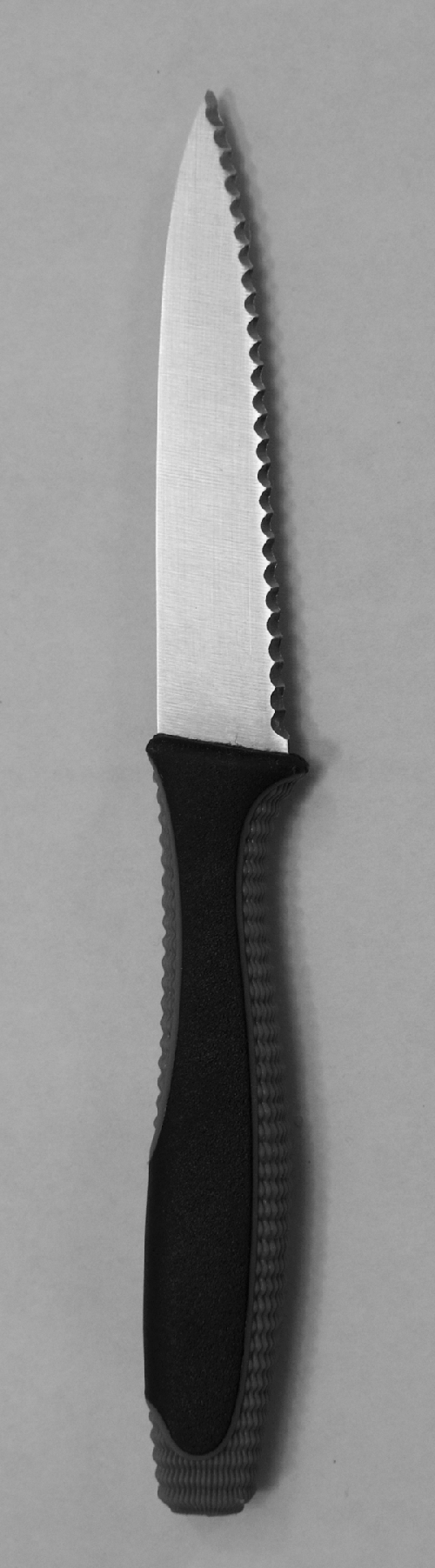

Paring knife. A paring knife has a small (~4″ /

10 cm) blade and is probably the most versatile knife in the kitchen. I’ve had some

chefs confide to me that their favorite knives are the scalloped paring knives, since

they are useful for cutting so many different types of items. They’re designed to be

held up off the cutting board, knife in one hand, food item in the other, for tasks such

as removing the core from an apple quarter or cutting out bad spots on a potato. I find

that the almost pencil-like grip design of some commercial paring knives allows me to

twirl and spin the knife in my fingers, so I can cut around something by rotating the

knife instead of rotating the food item or twisting my arms. Personally, I prefer a

scalloped blade—one that is serrated—because I find it cuts more easily.

Bread knife. Look for an offset bread knife, which has the

handle raised up higher than the blade, avoiding the awkward moment of

knuckles-touching-breadboard at the end of a slice. While not an everyday knife, in

addition to cutting bread and slicing bagels, bread knives are also handy for cutting

items like oranges, grapefruits, melons, and tomatoes because of the serrated

blade.

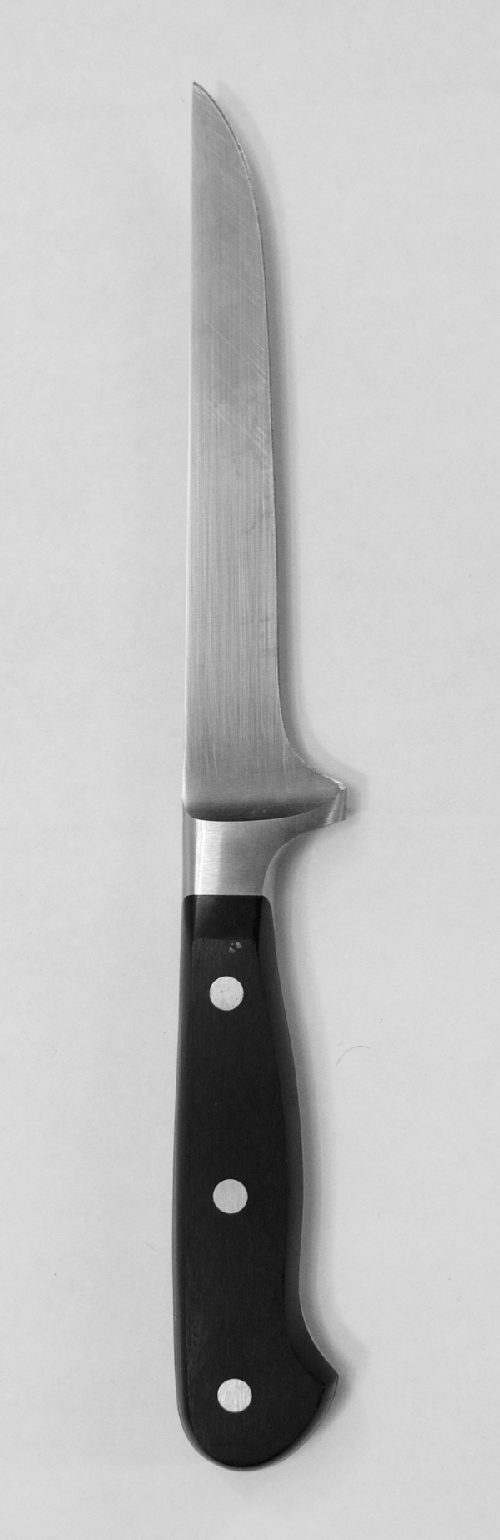

Boning knife. If you plan to cook fish and meat,

consider acquiring a boning knife, which is designed to sweep around bones. A boning

knife has a thinner, more flexible blade than a chef’s knife, allowing you to avoid

hitting bones, which would otherwise nick and damage the knife blade. Some chefs find

them indispensable, while others rarely use them.

The sound of a failed disk drive grinding itself

down is pretty bad, but watching someone use a knife improperly is far worse. I swear,

if I were going to develop PTKD (post-traumatic kitchen disorder) over something, it’d

be from watching people use knives improperly.

I treat knives as the second most dangerous implements in the average kitchen.

(Microplanes and mandolins hold the top spot.) When using a knife, I’m always thinking

about the “failure mode.” If it slips, or something goes wrong, how is it going to go

wrong? Where is the knife going to go if it does slip? How can I use the knife and

position myself such that if an exception does occur, it isn’t fatal? Of course,

getting a good, clean cut and keeping the knife in good working order are also

important. Here are my top tips for knife usage:

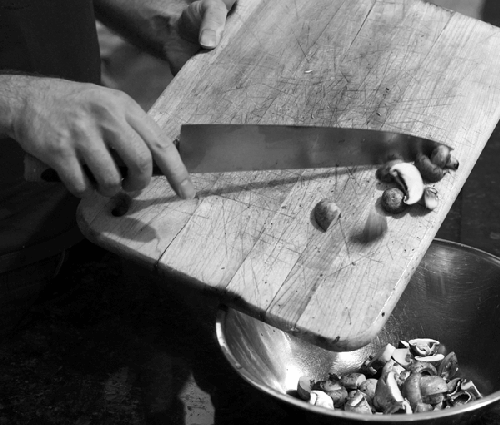

Feed the food into the cutting plane with your fingers positioned so that

they can’t get cut. Keep the fingers of the hand holding the item curled back,

so that if you misjudge where the knife is, or it slips, your fingers are out of

harm’s way. You can also rub the upper side of the knife against your knuckles

to get better control over the location of the knife. Use a smooth, long motion

when cutting. Don’t saw back and forth, and don’t just press straight down

(except for soft things like a block of cheese or a banana). Let the knife do

the work!

When scraping food off a cutting board, flip the knife over and use the dull

side of the blade. This will keep the sharpened side sharper.

There’s more than one way to hold a knife: try using a “pinch grip” instead

of a “club grip.” A pinch grip allows for more flexibility, as it gives you more

dexterity in moving the knife.

Don’t use the edge of the blade to whack or crack hard objects, such as a

walnut shell or a coconut; you’ll nick it! Repeat after me: knives are

not hammers (you know who you are). Unless, of course, you have a

commercial knife that has a butt that actually is a hammer, in which case, go

right ahead... You can, however, use the side of the blade as a quick way to

crush garlic or pit cherries or olives. Place food on board, place side of blade

on top of food, press down on blade with fist.