2. Methods of Heat Transfer

There are three methods of transferring heat into

foods: conduction, convection, and radiation. While the heating method doesn’t change the

temperature at which chemical reactions occur, the rate of heat transfer is different

among them, meaning that the length of time needed to cook identical steaks via each

method will be different. The table below shows the common cooking techniques broken out

by their primary means of heat transfer.

2.1. Conduction

Conduction is the simplest type of heat transfer to understand because it’s the most

common: it’s what you experience whenever you touch a cold countertop or grasp a warm

cup of coffee. In cooking, those methods that transfer heat by direct contact between

food and a hot material, such as the hot metal of a skillet, are conduction methods.

Dropping a steak onto a hot cast iron pan, for example, causes thermal energy from the

skillet to be transferred to the colder steak as the neighboring molecules distribute

kinetic energy in an effort to equalize the difference in temperature.

| |

Conduction

|

Convection

|

Radiation

|

|---|

|

Description

|

Heat passes by direct contact between two materials

|

Heat passes via movement of a heated material against a colder

material

|

Heat is transferred via electromagnetic radiation

|

|

Example

|

Steak touching pan; pan touching electric burner

|

Hot water, hot air, or oil moving along outside of food

|

Infrared radiation from charcoal

|

|

Uses

|

Sautéing

Searing

|

Dry heat methods: Baking/roasting, deep-fat

frying

Wet heat methods: Boiling, braising/water bath,

pressure cooking, simmering/poaching, steaming

|

Microwaving

Broiling

Grilling

|

Cooking methods listed by type of heat transfer. (Frying is a dry-heat

method because it does not involve moisture.)

2.2. Convection

Convection methods of heat transfer—baking, roasting,

boiling, steaming—all work by circulating a hot material against a cold one, causing the

two materials to undergo conduction to transfer heat. In baking and roasting, the hot

air of the oven imparts the heat; in boiling and steaming, it’s the water that does

this.

Those heat methods that involve water are called wet heat methods; all others fall

into the dry heat category. One major difference between these two categories is that

wet methods don’t reach the temperatures necessary for Maillard reactions or

caramelization (with the exception of pressure cooking, which does get up to temperature

while remaining moist). The flavorful compounds produced by Maillard reactions in

grilled or oven-roasted items won’t be present in braised or stewed foods: steamed

carrots, for example, won’t undergo any caramelization, leaving the food with a subtler

flavor. Brussels sprouts are commonly boiled and widely hated. Next time you cook them,

quarter them, coat with olive oil and sprinkle with salt, and cook them under a broiler

set to medium.

Note:

Water is an essential material in cooking, and not just for its heat transfer

properties. Rice cookers work by noticing when the temperature rises above 212°F /

100°C. At that point, there’s no water left, so they shut off.

Another key difference between most of the dry versus wet methods is the higher

speed of heat transfer typical in wet methods. Water conducts heat roughly 23 times

faster than air (air’s coefficient of thermal conductivity is 0.026, olive oil’s is

0.17, and water’s is 0.61), which is why hard-cooked eggs finish faster in a wet

environment even at a lower temperature.

Note:

Try it! Cook one egg for 30 minutes in a 325°F / 165°C oven and another for 10

minutes in a 212°F / 100°C water bath. You need to leave the egg in the oven for 20

minutes longer to get the same results.

One exception to this wet-is-faster-than-dry rule is deep-fat frying. Oil is

technically dry (there’s no moisture present), but for culinary purposes it acts a lot

like water: it has a high rate of heat transfer with the added benefit of being hot

enough to trigger a large number of caramelization and Maillard reactions. (Mmm,

donuts!)

Wet methods have their drawbacks (including, depending on the desired result, the

lack of the aforementioned chemical reactions). While the subtler flavors achieved

without browning reactions can be desirable, as in a gently cooked piece of fish, it’s

also much easier to overcook foods with wet methods. When cooking meat, the hot liquid

interacting with it can

quickly raise its temperature above 160°F / 71°C, the point at which a significant

percentage of the actin proteins in meats are denatured, giving the meat a tough, dry

texture. For pieces of meat with large amounts of fat and collagen (such as ribs,

shanks, or poultry legs), this isn’t as much of an issue, because the fats and collagen

(which converts to gelatin) will mask the toughness brought about by the denatured

actin. But for leaner cuts of meat, especially fish and poultry, take care that the meat

doesn’t get too hot! The trick for these low-collagen types of meats is to keep your

liquids at a gentle simmer, around 160°F / 71°C, and minimize the time that the meat

spends in the liquid.

Note:

Even water in its gaseous form—steam—can pack a real thermal punch. While it

doesn’t conduct heat anywhere nearly as quickly as water in its liquid form, steam

gives off a large amount of heat due to the phase transition from gas to liquid,

something that air at the same temperature doesn’t do. As the steam comes into contact

with colder food, it condenses, giving off 540 calories (not to be confused with “food

calories,” which are technically kilocalories) of energy per gram of water, causing

the food to heat up that much more quickly (1 calorie raises the temperature of 1 gram

of water by 1°C).

Steamed vegetables, for example, cook quickly not just because they’re in a 212°F

/ 100°C environment, but also because the water vapor condensing on the food’s surface

imparts a lot of energy. Cheetos, like most “extruded brittle foams” we eat, gain

their puff by being expelled under pressure and heat, which causes them to “steam

puff.” (Think of it as the industrial version of popping popcorn.) There’s a lot of

energy in steam. For this reason, when pouring boiling water through a colander over a

sink, you should be sure to pour away from yourself so that the steam cloud (and any

splashed liquid) doesn’t condense on your face!

2.3. Radiation

Radiant methods of heat transfer impart energy in the form of electromagnetic

energy, typically microwaves or infrared radiation. The warmth you feel when sunlight

hits your skin is radiant heat.

You can create a “heat shield” out of aluminum foil if part of a dish

begins to burn while broiling. The aluminum foil will reflect the thermal

radiation.

In cooking, radiant heat methods are the only ones in which the energy being applied

to the food can be either reflected or absorbed by the food. You can use this reflective

property to redirect energy away from parts of something you’re cooking. One technique

for baking pie shells, for example, includes putting foil around the edge, to prevent

overcooking the outer ring of crust. Likewise, if you’re broiling something, such as a

chicken, and part of the meat is starting to burn, you can put a small piece of

aluminum foil directly on top of that part of meat.

2.4. Combinations of heat

The various techniques for applying heat to food differ in other ways than just the

mechanisms of heat transfer. In roasting and baking we apply heat from all directions,

while in searing and sautéing heat is applied from only one side. This is why we flip

pancakes (stovetop, heat from below) but not cakes (oven, heat from all directions). The

same food can turn out vastly different under different heat conditions. Batter for

pancakes (conduction via stovetop) is similar to that for muffins (convection via

baking) and waffles (conduction), but the end result differs widely.

To further complicate things, most cooking methods are actually combinations of

different types of heat transfer. Broiling, for example, primarily heats the food via

thermal radiation, but the surrounding air in the oven also heats up as it comes in

contact with the oven walls, then comes in contact with the food and supplies additional

heat via convection. Likewise, baking is primarily convection (via hot air) but also

some amount of radiation (from the hot oven walls). “Convection ovens” are nothing more

than normal ovens with a blower inside to help move the air around more quickly. All

ovens are, by definition, convection ovens, in the sense that heat is transferred by the

movement of hot air. Adding a fan just moves the air more quickly, leading to a higher

temperature difference at the surface of the (cold) food you’re cooking.

To a kitchen newbie, working with combinations of heat might be frustrating, but as

you get experience with different heat sources and come to understand how they differ,

you’ll be able to switch methods in the middle of cooking to adjust how a food item is

heating up. For example, if you like your lasagna like I do—toasty warm in the middle

and with a delicious browned top—the middle needs to get hot enough to melt the cheese

and allow the flavors to meld, while the top needs to be hot enough to brown. Baking

alone won’t generate much of a toasted top, and broiling won’t produce a warm center.

However, baking until it’s almost done and then switching to the broiler achieves both

results.

Note:

The convenience food industry cooks with combinations of heat, too, cooking some

foods in a hot oven while simultaneously hitting them with microwaves and infrared

radiation to cook them quickly.

When cooking, if something isn’t coming out as you

expect—too hot in one part, too cold in another—check to see whether switching to a

different cooking technique can get you the results you want.

If you’re an experienced cook, try changing heat sources as a way of creating a

challenge for yourself: adapt a recipe to use a different source of heat. In some cases,

the adaptation is already common—pancake batter, when deep-fat fried, is a lot like

funnel cakes. But try pushing things further. Eggs cooked on top of rice in a rice

cooker? Chocolate cookies cooked in a waffle iron? Fish cooked in a dishwasher? Why not?

It might be unconventional, but heat is heat. Sure, different sources of heat

transfer energy at different rates, and some are better suited to transitioning the

starting thermal gradient (edge to center) of the food to the target thermal gradient.

But there are invariably similar enough heat sources worth trying. And you can push it

pretty far: fry an egg on your CPU, or cook your beans and sausage on an engine block

like some long-haul truck drivers do! As a way of getting unstuck—or just playing

around—it’s fun to try.

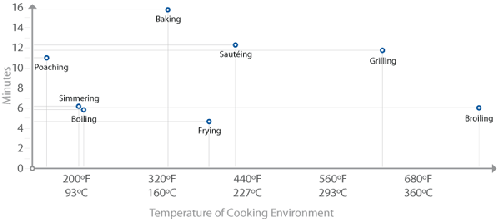

Cooking methods plotted by rate of heat transfer. This plot shows the

amount of time it took to heat the center of uniformly sized pieces of tofu from

40°F / 4°C to 140°F / 60°C for each cooking method. Pan material (cast iron,

stainless steel, aluminum) and baking pan material (glass, ceramic) had only minor

impact on total time for this experiment and are not individually

listed.