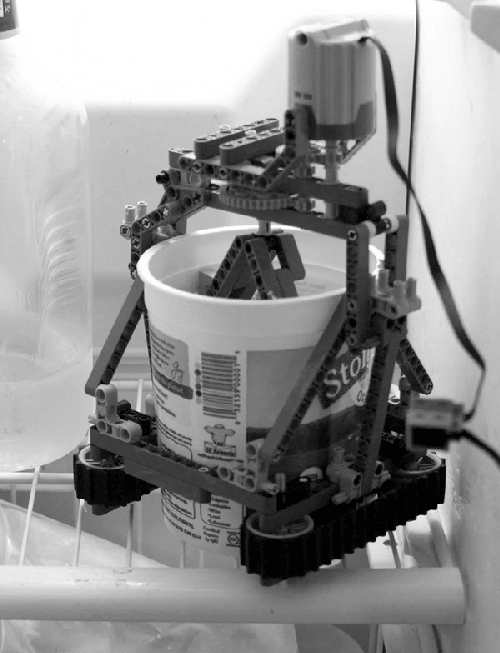

Don’t have an ice cream maker, but have a pile of Lego bricks? Make your own ice

cream maker! Ice cream is made from a base (traditionally, milk or cream with flavorings

added) that’s agitated as it freezes. Stirring the base as it sets prevents the ice

crystals that form from solidifying into one large ice cube.

Of course, the fun with Lego is in figuring out how to build things with it. To make

an ice cream maker, grab a Lego Technic kit and an XL motor and snap away. Once you have

your motorized stand and agitator put together, mix up your base, transfer it to a large

yogurt container, and prechill it by putting the container in your freezer until the

base just begins to freeze, about 30 to 60 minutes. Once the base is cold (but not

frozen!), slide the container into your Lego rig, place it back in the freezer, and flip

the switch. (Dangle the battery outside, because cold environments slow down the

chemical reactions that generate energy.) Check on your ice cream every 10 minutes or

so, until it begins to set. You’ll probably need to stop the motor before the ice cream

completely sets, lest the torque tear your Lego creation apart.

In a pan, create a simple syrup by bringing to a

boil: ½ cup (120g) water ¼ cup (50g) sugar

Once the simple syrup has reached a boil, remove from heat and add: 15 oz (425g = 1 can) pears (if fresh, peel and core

them) 1 teaspoon (5g) lemon juice

Purée with an immersion blender, food processor, or standard blender, being careful

not to overfill and thus overflow the container. Transfer to a sorbet maker and churn

until set. If you don’t have a sorbet maker, you can make sorbet’s sister dish, granita,

by freezing the mix in a 9″ × 13″ / 23 cm × 33 cm glass pan, using a spoon to stir up

the mixture as it sets. Notes The lemon juice helps reduce the sweetness brought about by the sugar.

The sugar is added not just for taste, but also to lower the freezing point of the

liquid (salt does the same thing). Adding a small quantity of alcohol will further

help prevent the sorbet from setting into a solid block. Ice cream and sorbets

have a fascinating physical structure: as the liquid begins to freeze, the

remaining unfrozen liquid becomes more concentrated in sugar, and as a result, the

freezing point of the unfrozen portions drops. Harold McGee’s On Food

and Cooking (Scribner) has an excellent explanation of this process for

the curious reader. You can make a more concentrated simple syrup and then dilute it

(after letting it cool) with champagne, pear brandy, or ginger brandy. The alcohol

is a solvent and will help carry the smells. Alternatively, try adding a pinch of

ginger powder, cardamom, or cinnamon either in the sorbet liquid or as a

garnish.

|

Gail Vance Civille is a self-described “taste and smell geek” who started

out working as a sensory professional at General Foods’ technical center and is now

president and owner of Sensory Spectrum, Inc., in New Providence, New

Jersey.

How does somebody who is trained to think about flavor,

taste, and sensation perceive these things differently than the

layperson?

The big difference between a trained taster and an untrained taster is not that your

nose or your palate gets better, but that your brain gets better at sorting things out.

You train your brain to pay attention to the sensations that you are getting and the

words that are associated with them.

It sounds like a lot of it is actually about the ability to

recall things that you’ve experienced before. Are there things that one can do to help

get one’s brain organized?

You can go to your spice and herb cupboard and sort and smell the contents. For

example, allspice will smell very much like cloves. That’s because the allspice berry

has clove oil or eugenol in it. You’ll say, “Oh, wow, this allspice smells very much

like clove.” So the next time you see them, you might say, “Clove, oh but wait, it could

be allspice.”

So, in cooking, is this how an experienced chef understands

how to do substitutions and to match things together?

Right. I try to encourage people to experiment and learn these things so that they

know, for example, that if you run out of oregano you should substitute thyme and not

basil. Oregano and thyme are chemically similar and have a similar sensory impression.

You have to be around them and play with them in order to know that.

With herbs and spices, how do you do that?

First you learn them. You take them out, you smell them, and you go, “Ah, okay,

that’s rosemary.” Then you smell something else and you go, “Okay, that’s oregano,” and

so on. Next you close your eyes and put your hand out, pick up a bottle, and smell it

and see if you can name what it is. Another exercise to do is to see if you can sort

these different things into piles of like things. You will sort the oregano with the

thyme and, believe it or not, the sage with the rosemary, because they both have

eucalyptol in them, which is the same chemical and, therefore, they have some of the

same flavor profile.

What about lining up spices and foods, for example apples

and cinnamon?

You put cinnamon with an apple because the apple has a woody component, a woody part

of the flavor like the stem and the seeds. And the cinnamon has a wood component, and

that woody component of the cinnamon sits over the not-so-pleasant woodiness of the

apple, and gives it a sweet cinnamon character. That’s what shows. Similarly, in

tomatoes you add garlic or onion to cover over the skunkiness of the tomatoes, and in

the same way basil and oregano sit on top of the part of the tomato that’s kind of musty

and viney. Together they create something that shows you the best part of the tomato and

hides some of the less lovely parts of the tomato. That’s why chefs put certain things

together. They go, they blend, they merge and meld, and actually create something that’s

unique and different and better than the sum of the parts.

It takes a while to get at that level, because you have to really feel confident as

both a cook and getting off the recipe. Please, get off the recipe. Let’s get people off

these recipes and into thinking about what tastes good. Taste it and go, “Oh, I see

what’s missing. There’s something missing here in the whole structure of the food. Let

me think about how I’m going to add that.” I can cook something and think to myself,

there’s something missing in the middle, I have some top notes and I have

maybe beef and it’s browned and it has really heavy bottom notes. I think of flavor like

a triangle. Well, then I need to add oregano or something like that. I don’t need lemon,

which is another top note, and I don’t need brown caramelized anything else because

that’s in the bottom. You taste it, and you think about how you are going to add

that.

How does somebody tasting something answer the question,

“Hey, if I wanted to do this at home, what should I do?”

I can sit in some of the best restaurants in the world, and not have a clue what’s

in there. I can’t taste them apart, it’s so tight. So it’s not just a matter of

experience; it’s also a matter of the experience of the chef. If you have a classically

trained French or Italian chef, they can create something where I will be scratching my

head, going “Beats me, I can’t tell what’s in here,” because it’s so tight, it’s so

blended, that I can’t see the pieces. I only see the whole.

Now this does not happen with a lot of Asian foods, because they are designed to be

spiky and pop. That’s why Chinese food doesn’t taste like French and Italian food. Did

you ever notice that? Asian foods have green onions, garlic, soy, and ginger, and

they’re supposed to pop, pop, pop. But the next day they’re all blending together and

this isn’t quite so interesting.

This almost suggests that if one is starting out to cook,

that one approach is to go out and eat Asian food and try to identify the

flavors?

Oh, definitely. That’s a very good place to start, and Chinese is a better place to

start than most. I’ve had some Asian people in classes that I’ve taught get very

insulted when I talk about this, and I’m like, no, no, no, that’s the way it’s

supposed to be. That’s the way Asian food is; it’s spiky and

interesting and popping, and that’s not the way classic European food, especially

southern European food, is.

In the case of classic European dishes, let’s say you’re out

eating eggplant Parmesan, and it’s just fantastic. How do you go about trying to

figure out how to make that?

I would start identifying what I am capable of identifying. So you say, “Okay, I get

tomato, and I get the eggplant, but the eggplant seems like it’s fried in something

interesting, and not exactly just peanut oil or olive oil. I wonder what that is?” Then

I would ask the waiter, “This is very interesting. It’s different from the way I

normally see eggplant Parmesan. Is there something special about the oil or the way that

the sous chef fries the eggplant that makes this so special?” If you ask something

specific, you are more likely to get an answer from the kitchen than if you say, “Can

you give me the recipe?” That is not likely to get you an answer.

When thinking about the description of tastes and smells, it

seems like the vocabulary around how we describe the taste is almost as

important.

It’s the way that we communicate our experience. If you said “fresh” or “it tasted

homemade,” you could mean many things. These are more nebulous terms than, say, “You

could taste the fried eggplant coming through all of the sauce and all of the cheese.”

This is very, very specific, and in fact, “fresh” in this case is freshly fried

eggplant. I once had a similar situation with ratatouille in a restaurant. I asked the

waiter, “Could you tell me please if this ratatouille was just made?” The waiter said,

“Yes, he makes it just ahead and he doesn’t put all the pieces together until just

before we serve dinner.” When people say “homemade,” they usually mean that it tastes

not sophisticated and refined, but that it tastes like it had been made by a good home

cook, so it’s more rustic, but very, very well put together.

Is there a certain advantage that the home chef has because

he is assembling the ingredients so close to the time that the meal is being

eaten?

Oh, there’s no question that depending upon the nature of the food itself, there are

some things that actually benefit from sitting long in the pot. Most home chefs, either

intuitively or cognitively, have a good understanding of what goes with what, and how

long you have to wait for it to reach its peak.

You had said a few minutes ago, “We need to get off the

recipe.” Can you elaborate?

When I cook, I will look at seven or so different recipes. The first time I made

sauerbraten, I made it from at least five recipes. You pick things from each based on

what you think looks good, and what the flavor might be like. I think the idea of

experimenting in the classic sense of experimenting is fine. Geeks should be all about

experimenting. What’s the worst thing that’s going to happen? It won’t taste so great.

It won’t be poison, and it won’t be yucky; it just may not be perfect, but that’s okay.

I think when you do that, it gives you a lot more freedom to make many more things

because you’re not tied to the ingredient list. The recipe is, as far as I’m concerned,

a place to start but not the be all, end all.