More and more families are having just one

baby, yet ‘only child’ stereotypes persist. Here’s what the experts say.

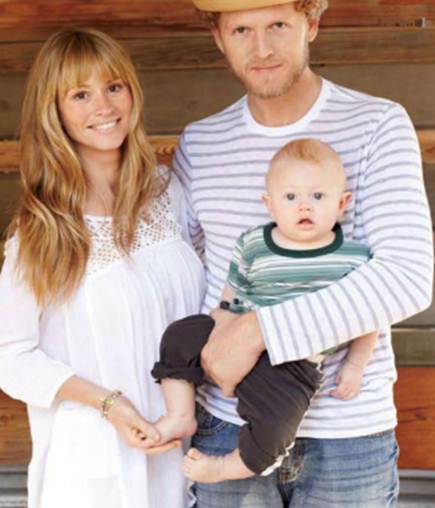

Like most parents

Like most parents, my husband and I always

tried to make perfect choices, from the seemingly small (the perfect diaper

pail) to the potentially life-changing (deciding how many kids to have). The

longer we had our one child, the more we felt she was all we needed, yet the

old myths continued to worry us: Would she be lonely and spoiled? Were we being

selfish by not giving her a sibling? Would the task of caring for us in our old

age fall on her shoulders alone?

Having

only one baby can benefit the whole family.

Thanks to delayed childbearing,

environmental concerns, the current economic crisis and other factors,

single-child families like ours are no longer the rarity they once were:

According to Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey in 2011, an estimated 15

million U.S. households today have one child. Still, many parents who—whether

by choice or necessity—are contemplating stopping at one continue to struggle

with misconception-fueled confusion and guilt. If you’re in this spot, here’s

what the research and experts can tell you.

Is one really a lonely number?

Many parents feel they need to supply a

sibling for their first child so that he or she will have a built-in friend.

Not true, says social psychologist Susan Newman, Ph.D., the “Singletons”

blogger for Psychology Today and author of The Case for the Only

Child (Heath Communications, Inc.). Newman cites two Ohio State University

studies demonstrating that while only children may have a very small social

deficit in kindergarten, by middle school they have as many friends as their

counterparts with siblings.

Only children have a vested interest in

cultivating skills like sharing and compromise, Newman says. “They realize

early on that they need their friends—their sibling substitutes—and that bad

behavior won’t preserve those relationships,” she explains. Indeed, I’ve

observed a strong diplomatic quality in my daughter that has allowed her to

easily make and keep friends.

Spare the sibling, spoil the child?

It is true that singletons enjoy more

access to parental attention and material resources than a child with siblings.

At least partly as a result, they tend to be well- adjusted high achievers (see

“An ‘Online’ Report Card,” pg. 63). Studies have consistently found them to

have not only greater cognitive abilities, but also higher levels of maturity

and social sensitivity—not characteristics of a “spoiled” child. And rather

than overindulging, many parents of an only child find it a relief in

economically stressful times just to be able to provide necessities for the

family.

many

parents of an only child find it a relief in economically stressful times just

to be able to provide necessities for the family

Studies on birth order actually relegate

feelings of entitlement and “spoiling” to the baby of the family. Psychologist

Kevin Leman, Ph.D., author of The Birth Order Book (Revell), explains

that because parents are often “taught out” when the last-born child arrives,

they let him or her slide on chores or give in easily to his or her tantrums.

These are the same parents who made every activity with their first-born (who,

of course, began as an “only”) instructional. Laden with high parental

expectations, the only (or first-born) child naturally wants to achieve and

please.

What about elder care?

If you think you should have more than one

child to care for you when you’re old, forget about it: There are no guarantees

that adult children will equally share the burden.

In fact, one child (in our case, my older

sister) typically shoulders it anyway, and elder care can be a source of conflict

instead of a comfort. Research commissioned by the Home Instead Senior Care

network found that 46 percent of family caregivers say their sibling

relationships deteriorated because of their siblings’ unwillingness to share

care.

Making the choice

For most people, the family size “decision”

happens over time. It’s based partly on reason, partly on personal history and

usually topped off by a large portion of fate. Newman counsels parents who are

wrestling with how many children to have to resist feeling pressured and

instead ask themselves, “What kind of lifestyle do I want for me and my child?

And what can I realistically handle?”

In our case, finances were tight after our

daughter was born, because I had scaled back work and my husband changed

careers. And I am also a member of the growing Sandwich Generation, people who

are simultaneously facing child care and elder care responsibilities. I cannot

forget the many harried shopping trips during which I found myself chasing my

toddler daughter in one direction as my Alzheimer’s-stricken dad wandered off

in another.

Our daughter is 8 years old now and, for

us, the only-child myths have proved to be just that. She even balks at the

idea of having a sibling. When a singleton friend announced that his family was

adopting, she expressed concerns that we, too, might want to adopt. In

reassuring her, I put my own lingering worries to rest. Every family, I told

her, has to be just the right size for them, and she is, in fact, just enough

for us.

AN ‘ONUES’ report card

Psychologist Kevin Leman, Ph.D., author of The

Birth Order Book (Revell), maintains that only children share some general

characteristics, including the following: STRENGTHS Good decision-maker

Thorough and organized Ambitious and enterprising goal-setters Academically

minded and good problem-solvers WEAKNESSES Can be self-centered If parents

aren’t careful May be inflexible and hard to satisfy Not happy with surprises

Can be overly serious, driven or logical.