Escaping a Delhi summer is too tantalising to turn down, but

the sight of Tripura’s rolling green land, as our plane descended on Singerbhil

airport in Agartala, was a bigger relief than I imagined. To parched eyes

longing for green trees and cool shade, Tripura seems like paradise. Like most

people outside the Northeast, I knew next to nothing about the state, but

having got the chance I was determined to find out. I was armed with books,

printouts, more books, a carefully devised itinerary and a plan to cover as

much of the state’s cultural landscape as possible.

the Manu river

After a day wandering about Agartala, we were on our way up

to north Tripura to the town of Kailashahar through the densely forested hill

ranges of Baramura and Teliamura (mura means head). These verdant forests,

extremely troubled not so long ago, are home to some of Tripura’s indigenous

tribes - the Lushai, the Jamatiya and the Reang, among others. The winding hill

road then descended into the lush rice-growing valley of the Manu river, home

to the millions of Bengalis who first came here as refugees from neighbouring

Bangladesh. The land is folded, with even a few scattered tea gardens. Leaving

NH-44 and heading towards Kailashahar, we were in hilly country again. Deep in

these forested hills bordering Sylhet lies one of the crowning glories of

Tripura’s cultural heritage.

A passenger ferry

crossing the Rudrasagar lake to Neermahal

No one can tell with any certainty the identity of the

people who created the unique sculptures of Unakoti hill in these clouded

valleys of the Chawra stream. We arrived on a hot and humid Sunday afternoon.

Entire families of Bengalisand Reangs from Kailashahar and the neighbouring city

of Dharmanagar were out in force, taking in the sights and offering puja. The

object of their veneration was a stupendous thirty-foot bas-relief of a Shiva

face, locally called the Unakotishwar Kalbhairava.

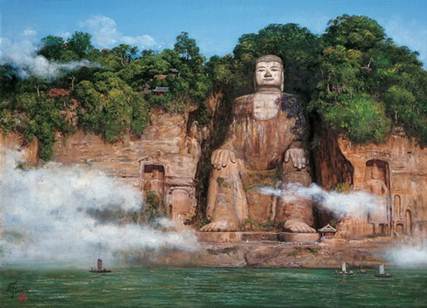

A giant Buddha

To suddenly encounter it is a shock. A cursory view

convinced me that I was looking at a giant Buddha face, what with the shape of

the head and the gigantic ears. Then I noticed the third eye. And then I saw

the massive ear-rings, distinctly tribal, the slightly showy moustache and the

un-Buddhist toothy grin. And finally the ten-foot long crown, reminiscent of

both classical Tamil sculpture as well as the face sculptures of the Bayon

temple in Cambodia. This image, along with two other similar faces on an

adjacent wall, and another collapsed one, forms the cornerstone of this amazing

valley. Although their antecedents are not known, informed guess-work by

historians suggests that these faces are the centre piece of a memorial gallery

for a now-forgotten tribal king who probably identified himself with a totemic

deity, Shibrai, the ur-Shiva of Tripura. Shaivite and Vaishnavite cults had

been firmly established among the tribes of the Tripuri hills by the ninth

century, vying for patronage with a strong Buddhist tradition.

Udaipur's tripurasundari

temple is a classic example of Tripuri architecture of a Bengali char chaala

roof surmounted with a buddhist stupa-like crown

Further uphill lay a plethora of images, large and small,

including a charming little grinning archer with a crown of feathers and two

giant female figures of astonishing vitality. The lack of historical

information has given rise to many myths, including the widely accepted one

that the word Unakoti (one less than a crore) refers to the number of petrified

Brahminical deities that lie in this valley, cursed by Shiva to remain here

till eternity for some minor infraction. However, what can be asserted with

some certainty is that these sculptures span a period of three hundred years

from roughly the ninth to the twelfth centuries AD.

Ganesha Brass

Figures

This is evident in the range of carving styles. A little

further down the valley, the stream descends in a small water fall, and flanking

it is a massive seated Ganesha, along with two equally huge standing

elephant-headed figures. You could call them Ganesha figures, except that

unlike that cuddly Puranic god beloved of merchants, these menacing forms had

up to six tusks each. They were quite different from the figures of the upper

pavilion if still tribal in their attire. A little to their left was a discreet

standing Vishnu, of even greater technical sophistication. It’s all extremely

dramatic, and it’s very tempting to wonder just how many more sculptures might

lie hidden in the surrounding forest, and how many more have been irreparably

lost in the intervening millennia.