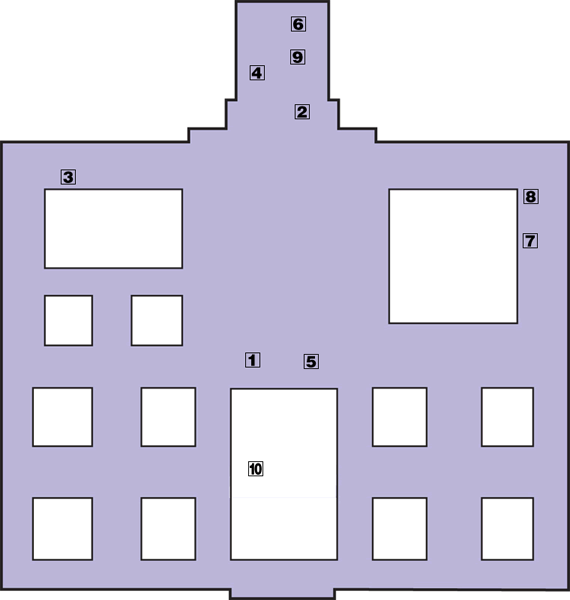

Further Features of El Escorial

El Escorial Floorplan

Cenotaphs

These

superb bronze sculptures on either side of the high altar are by an

Italian father and son team, Leone and Pompeo Leoni. On the left is

Carlos I (Emperor Charles V), shown with his wife, daughter and sisters;

opposite is Felipe II, three of his wives and his son, Don Carlos.

King’s Deathbed

It

was in this simple canopied bed that Felipe II died on 13 September

1598, it is said as “the seminary children were singing the dawn mass”.

The bed was positioned so that the king could easily see the high altar

of the basilica on one side and the mountains of the Sierra de

Guadarrama on the other.

The Martyrdom of St Maurice and the Theban Legion

This

ethereal work by El Greco (1541–1614) was intended for an altar in the

basilica but Felipe II found the style inappropriate and relegated it to

the sacristy. El Greco never received another royal commission.

Portrait of Felipe II

In

this stately painting by Dutch artist Antonio Moro, the king, then aged

37, is wearing the suit of armour he wore at the battle of St Quentin

in 1557. It was to be Felipe’s only victory on the battlefield.

Cellini Crucifix

Florentine

master craftsman Benvenuto Cellini sculpted this exquisite image of

Christ from a single block of Carrara marble. It was presented to Felipe

II in 1562 by Francisco de Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany.

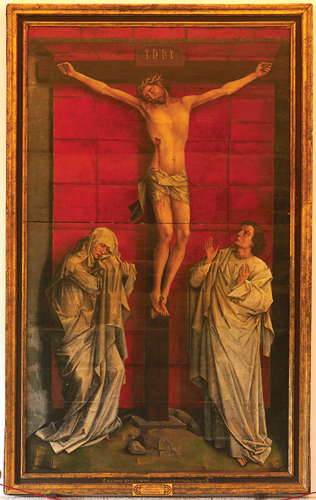

Calvary

This

moving painting is by 15th-century Flemish artist Rogier van der

Weyden. Felipe II knew the Netherlands well and was an avid collector of

Flemish art.

Calvary

Last Supper

Venetian

artist Titian undertook numerous commissions for El Escorial.

Unfortunately this canvas was too big to fit the space assigned to it in

the monks’ refectory and was literally cut down to size.

Inlay Doors

One

of the most striking features of the king’s apartments is the superb

marquetry of the inlay doors. Made by German craftsmen in the 16th

century, they were a gift from Emperor Maximilian II.

King’s Treasures

A cupboard in the royal bedchamber contains more than a dozen priceless objets d’art. They include a 12th-century chest made in Limoges and a 16th-century “peace plate” by Spanish craftsman Luís de Castillo.

Queen’s Room Organ

The

corridors of El Escorial would have resounded to monastic plainchant

but the organ also met with royal approval. This rare hand organ dates

from the 16th century and is decorated with Felipe II’s coat of arms.

King Felipe II

When Felipe II took

over the reins of government from his father Carlos I in 1556, he

inherited not only the Spanish kingdoms of Castile and Aragon, Naples,

Sicily, Milan and the Low Countries, but also the territories of the New

World. Defending this farflung empire embroiled him in constant

warfare. The drain on the royal coffers (despite the prodigious influx

of gold and silver from the Americas) led to unpopular tax increases at

home and eventual bankruptcy Felipe’s enemies, the Protestant Dutch,

their English allies and the Huguenot French, set out to blacken his

reputation, portraying him as a cold and bloodthirsty tyrant. Today’s

historians take a more objective view, revealing him to have been a

conscientious, if rather remote, ruler and a model family man with a wry

sense of humour. On one occasion he startled the monks of El Escorial

by encouraging an Indian elephant to roam the cloisters and invade the

monastic Cells.

Top 10 El Escorial Statistics