We are wading back to the anchored skiff

after and slowish morning on the sand-flats, when our guide stops, crouches,

and points urgently into the shallow sea. Out goes James’s fly-line, the little

shrimp pattern pitches down, a silvery fin wags briefly above the surface. his

rod bucks and the reel begins to whizz like a dentist’s drill - it has taken

more than 20 years for this to happen, but finally my son has evolved into Homo

piscatorius.

The

Mojito Coast

For our first-ever fishing safari together,

I had little hesitation in choosing Cuba. Of the 30-odd countries where I‘ve

swum my hooks, this is the one I have most revisited: its maritime wildernesses

have only recently been opened up to sportsmen, and it’s as offbeat and funky a

destination as any I know.

This is my ninth trip, but for the first

time we are bypassing Havana entirely; instead, the itinerary begins in the

provincial city of Holguin. Holidaymakers who jet in to the capital or one of

the seaside resorts seldom see just how big an island this is (Cuba has some

5,000 miles of coastline and the Caribbean’s only railway system), but our

four-hour charabanc drive northwards through the heartlands of Las Tunas and

Camagüey also reveals how lush it can be. We speed past citrus orchards, walnut

groves and rolling dairy pasture green and pleasant enough to he in parts of

Devon — if you leave out the turkey buzzards and those cheery billboards

advertising ‘Socialismo o Muerte’.

Cuba

has some 5,000 miles of coastline and the Caribbean’s only railway system

They don’t see many tourists in the

sugarcane township of Brasil, our home for the coming week. Stately matrons

stop and stare from beneath nylon parasols as our bus descends the slip road,

where rice has been strewn to dry along the verge. The outskirts are a

disconcerting jumble of Bulgarian-style concrete tenements, cactus-fenced

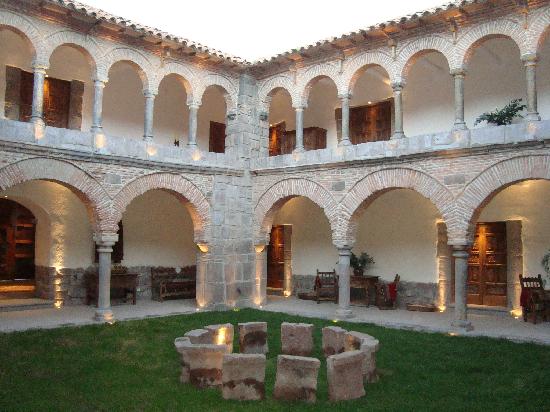

fields, and frangipani. The refinery has been mothballed, and we are staying at

La Casona, the former manager’s house — an elegant colonial-style building

facing the civic square. The rooms are spacious enough (one had its own bar,

where we held an impromptu cocktail party), but essentially ramshackle. Several

of the shower heads deliver electric shocks; there is only one remote control

between all the air-con units in the place: and if you found something on your

pillow it wasn’t going to be a chocolate. But we had come for some hardcore

angling action, not spa treatments: we were ready to kick some fin!

The

refinery has been mothballed, and we are staying at La Casona, the former

manager’s house — an elegant colonial-style building facing the civic square.

A 40-minute commute north lies Cayo Romano,

several hundred square miles of largely uninhabited mangrove islands in a

restricted zone where just a few tourist boats are allowed each week. Although

backward in some departments (human rights and plumbing spring to mind), Raúl

Castro’s regime is keen on its nature reserves: this one is protected by a

military checkpoint, partly for the benefit of the turtles and ibis population,

hut also to prevent local citizens accessing that geopolitical gulf that leads

to Florida, and freedom. As a result, there is abundant marine life, and

minimal angling pressure. Fifteen years ago, I was in one of the first groups

to explore a similar region off Cuba’s southern coast (the Jardines de la

Reina), and the sport there was truly outstanding. But such places can soon be

spoiled by over-development The popularity of flats fishing’ — the light-

tackle pursuit of shallow-water species such as bonefish and tarpon — is

growing every year, and has caught on from Christmas Island to Venezuela. So,

if you’re looking for somewhere a little ‘off piste’, I’d strongly recommend

toting your tackle here, sooner rather than later.

Fifteen

years ago, I was in one of the first groups to explore a similar region off

Cuba’s southern coast

After omelettes and powerful coffee at

5.30am, our group of seven fanaticos crams into the minibus, and we’re away up

the causeway towards the dock. Great vistas of mangrove keys stretch out on

either side, lacing the salt breeze with their medicinal tang. Even at dawn,

the weather is unsettled: a flamingo cloudscape to the east suggests we will

not get the clear, sunshiny conditions we require for sighting our quarry, but

of course we are brimful with optimism. If anglers ever stopped being

idealists, they would end up in the bughouse. At the thatched cabin, there

ensues a frenzy of tackling up our guide Yoandry (a former coastguard and, at

27, the same age as James) helps us assemble my collection of six rods. and

before long his sleek Mitzi skiff scooting out to sea, the outboard sending up

a proud rooster-tail of spray.

On his first morning we are aiming to

introduce my son to Albitta vulpes — the ‘pale fox’, or bonefish. Many

sportsmen regard this as the ideal quarry, and certainly it’s my favourite:

handsome, wary and powerful, ‘bones’ leave their deep-water refuge once the

tides begin to flood the shallows, and eagerly graze on the crustacea flushed

out of the substrate. Sometimes they cruise the mangrove carousels, snacking

off the tiffin sheltering in these tidal forests: at other times you see them

scurrying across the open marl and pouncing on their prey. Large bone dogs are

solitary (anything over 10lb is a world-class specimen), but the smaller chaps

often travel in schools. Either way, they are exceedingly hard to spot. Their

mirrored flanks give them chameleon-like powers, and often you just discern an

innuendo of their presence - a puff of silt, a wink of fin, the faintest

ruffle of wake. Small wonder they are nicknamed the ‘grey ghost of the flats’.

Even

at dawn, the weather is unsettled

Whether wading or standing in the bow of

the boat, when you do target a bonefish you must be stealthy. The careless

clatter of a flybox, or scrunch of the guide’s push pole, will have old Houdini

Fins zigzagging away like snipe off a marsh. You should be prepared to make

long, delicate presentations at short notice, and often into the wind – harder

than it sounds, when there’s loose line to manage, the sun is broiling down and

you’ve contracted a serious case of ‘fin fever’ from all the adrenalin in your system.

James, who had just had one casting lesson back home, settled into the rhythm

with a natural athlete’s skill. Whereas, Dad was frequently unpicking knots of

Gordian intricacy, tangled in the mangroves and muttering in Desperanto. At one

stage, the insolent youth even advised me to ‘chill’ — and to think I used to

change his nappies.

When it does all come together, and a

bonedog feels the Judas kiss of your hook, he streaks in a halogen blaze for

the next parish. All engine and no hull, for his size this must be the

mightiest fish that swims. Bring him finally to hand, and you are cradling an

aquadynamic creature sculpted out of moonlight. He has little turquoise details

along the fins, a glassed in eye, and an underslung mouth that makes him look

like a genteel Morningside auntie cooling her soup spoon. If you hook a dozen

of these beguiling fish in a day, you will have had great sport. Out here they

average a good four pounds apiece, and I think of every one as a trophy.

He

has little turquoise details along the fins, a glassed in eye, and an

underslung mouth that makes him look like a genteel Morningside auntie cooling

her soup spoon.