Light, fluffy foods need two things: air and something to trap that air. This might seem

obvious, but without some way of holding on to air while cooking, baked goods would be flat.

This is where gluten comes in.Gluten is created when two proteins, glutenin and gliadin, come into contact and form

what chemists call crosslinks: bonds between two molecules that hold

them together. In the kitchen, this crosslinking is done by kneading doughs, and instead of

talking about crosslinks, bakers speak of developing the gluten: the two proteins bind and

then the resulting gluten molecules begin to stick together to form an elastic, stretchy

membrane. The same stretchy, elastic property is also responsible for helping trap air

bubbles in bread doughs: the gluten forms a 3D mesh that traps air generated by organisms

such as yeast and chemicals like baking powder.

Regardless of the rising mechanism, understanding how to control gluten formation will

vastly improve your baked goods. Do you want air bubbles to be trapped in the food, or do

you want them to escape as the food is cooked? Breads and cakes rely heavily on air for

texture, while cookies need less.

The easiest way to control the amount of gluten developed is to use ingredients that

have more (or less) of the glutenin and gliadin proteins. Wheat, of course, is the most

common source of gluten; rye and barley also have these proteins in small quantities. For

practical purposes, though, wheat flour is the primary source of gluten.

Note:

While rye has both glutenin and gliadin, it also contains substances that interfere

with their ability to form gluten.

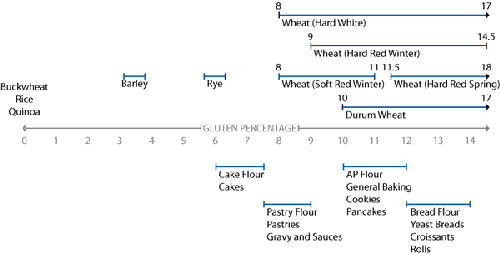

Gluten levels of various grains and common

flours.

Note:

Gluten levels will vary by both manufacturer and region. Since growing climate impacts

gluten levels—colder weather yields higher-gluten wheat—flour in, say, France, won’t be

identical to that grown in the U.S. Try working with a couple of different brands.

Here are three important things to keep in mind when working with gluten:

Use the appropriate type of

flour

Different types of wheat flours have different levels of gluten. Cake flour is low

in gluten; bread flour is high in gluten. (All-purpose flour should really be called

“general compromise” flour: it just takes the middle ground, which is fine when gluten

levels aren’t so important.) If you’re baking something that would suffer from the

elastic texture brought about by gluten—that should have a crumbly texture such as a

chocolate cake—use cake or pastry flours, and definitely avoid bread flour.

Fat inhibits gluten formation; water aids

it

Fats interfere with the formation of gluten. This is why cookies, which have a lot

of flour but also a lot of butter, still manage to crumble. And the opposite is true for

water, which helps with gluten formation. The more water there is—up to a point, we’re

not talking soup here—the more likely it is that glutenin and gliadin will bind.

Mechanical agitation and time develop gluten

Mechanical agitation (a.k.a. kneading)—physically ramming the glutenin and gliadin

proteins together—increases the chances for those crosslinks to form and thus increases

the amount of gluten in the food. Time, too, develops gluten, by giving the glutenin and

gliadin the opportunity to eventually crosslink as the dough subtly moves.

Note:

Flaky, crumbly baked goods = low levels of gluten.

Stretchy, elastic baked goods = high levels of gluten.

Even though gluten is the key variable in wheat flour and baking, it’s worth stepping

back and looking at what else is hanging out in flour: Protein: 8–13% Starch: 65–77% Fiber: 3–12% Water: ~12% Fat: ~1% Ash: ~1%

The two main compounds in flour are protein (primarily glutenin and gliadin) and

starch. Warmer growing climates lead to lower levels of protein and higher levels of

starch. Fiber is similar to starch in that both are carbohydrates—saccharides to

biochemists—but our bodies don’t have a mechanism to digest all forms of saccharides;

those that we can’t digest get classified as fiber (sometimes called nonstarch

polysaccharides). As for ash, this is the broad term given to trace elements and minerals

such as calcium, iron, and salt. Gluten is the most important reason for using flour in baking. Try this simple

experiment to separate out and “see” the gluten made by the proteins in flour. Start with about 1 cup (120g) of bread flour in a bowl and add just enough water so

that you can form a ball. Drop the ball of flour into a glass of water for an hour or so,

long enough for it to absorb water and allow the gluten to develop. After the ball has soaked, rinse the starches out by working the ball in your hands,

kneading it with your fingers, under slowly running tap water. Keep working the ball until

the water runs clear; only about a third of the original mass will be left. At this point,

all the starch has washed away. Notice how the part of the flour that remains has a very

elastic, stretchy quality to it: this is the gluten. You can drop the ball of gluten into

a glass of rubbing alcohol to separate out the glutenin and gliadin proteins—the gliadin

will form long, thin, sticky strands, and the glutenin will resemble something like tough

rubber. For comparison, try doing this with cake flour. You’ll find it almost impossible to

hold on to the ball under the running tap water—there’s just not enough gluten present in

cake flour to provide any structure to work with while washing away the starch

molecules. P.S. One food additive, transglutaminase, can be used to increase the gluten strength

in baked goods by physically increasing the crosslinks within wheat gluten. |

When making breads,

gluten impacts the texture not just with its stretchy, elastic quality, but also with its

ability to trap and hold on to air. If you’re making a loaf of bread using whole wheat flour

or grains low in gluten, adding some bread flour (start with 50% by weight) will result in a

lighter loaf. You can also add gluten flour, which is wheat flour that has had bran and

starch removed (yielding a 70%+ gluten content). Try making a loaf of whole wheat bread with

10% of the flour (by weight) replaced with gluten flour (sometimes called vital gluten

flour).

In addition to managing texture, gluten can also be used directly as an ingredient.

Consider the following recipe for seitan, a high-protein vegetarian ingredient often used as

a substitute for chicken or beef in vegetarian cooking. Seitan is like tofu, in that it is a

formed block or roll of proteins, in this case from wheat flour instead of soya

beans.

Mix together in a large bowl: ¾ cup (175g) water 2 tablespoons (35g) soy sauce 1 teaspoon (5g) tomato paste ½ teaspoon (5g) garlic paste, or 1 clove mashed and finely

diced

Add, and use a spoon to mix to a thick, elastic dough: 1 cup (160g) gluten flour (wheat flour that has had bran

and starch removed)

Shape the dough into a log and place into a saucepan. Add: 6 cups (1.5 liters) water ½ cup (144g) soy sauce

Bring to a boil and then simmer for an hour. Allow to cool before using. Notes The gluten flour—also called vital wheat

gluten—will take a few seconds to absorb the liquid. If you’re quick, you

can form the dough into a more shapely log and roll it a few times on a cutting

board. When cooking the seitan, if it comes out gluey, it wasn’t simmered long

enough. If you’re going to fry the resulting seitan, this is okay, but otherwise you

should return it to the simmering liquid and cook longer. Not sure what to do with seitan? Try thinking of it like tofu: slice off

pieces and panfry in oil; or shred the seitan, fry, and toss with a quick

sweet-and-sour sauce and serve with rice.

|

Measuring out too much (or not enough) butter when making mashed

potatoes won’t lead to disaster. But with baking, the error tolerance

in measurement—the amount you can be off by and still have acceptably good results—is much

smaller. How can you learn what measurements are important? Besides trying lots of experiments

and keeping detailed notes, you can look at differences between recipes. By looking at the differences, you can also see

what doesn’t matter so much. Consider the ingredients for the following two pie dough recipes. |

Joy of Cooking (8″ / 20 cm pie)

|

|---|

|

100%

|

240g

|

flour

| |

60%

|

145g

|

shortening (Crisco)

| |

11.25%

|

27g

|

butter

| |

25%

|

59g

|

water

| |

0.8%

|

2g

|

salt

| |

–

|

–

|

(no sugar)

|

|

Martha Stewart’s Pies & Tarts (10″ / 25 cm pie)

|

|---|

|

100%

|

300g

|

flour

| |

–

|

–

|

(no shortening)

| |

76%

|

227g

|

butter

| |

19.7%

|

59g

|

water

| |

2%

|

6g

|

salt

| |

2%

|

6g

|

sugar

|

The numbers in the first column are “baker’s percentages,” which normalize

the quantities to the quantity of flour by weight; the second column gives the gram

weights for one pie’s worth of dough.

Just comparing these two recipes, you can see that the ratio of flour to fats ranges

from 1:0.71 to 1:0.76, and that a higher percentage of water is called for in the

Joy of Cooking version. However, butter isn’t the same thing as shortening; butter is about 15–17% water,

whereas shortening is only fat. With this in mind, look at the recipes again: the Martha

Stewart version has 76g of butter (per 100g of flour), for about 62g of fat; the pie dough

with shortening has 60g of fat per 100g of flour. The quantity of water is also roughly

equal between the two once the water present in the butter is factored in. You won’t always find the ratios of ingredients between different recipes to be so

close, but comparing recipes is a great way to learn more about cooking and a good way to

determine which recipe to use when trying something new.

Note: There are two broad types of pie doughs: flaky and mealy. Working the fat into the

flour until it is pea sized and using a bit more water will result in a flakier dough

well suited to prebaked pie shells; working it until it has a cornmeal-like texture will

result in a more water-resistant, mealy, crumbly dough, which makes it better suited for

uses where it is filled with ingredients when baked.

|