6. 356°F / 180°C: Sugar Begins to Caramelize Visibly

Unlike the Maillard reaction, which requires the

presence of both amino acids and sugars and has a number of interdependent variables

influencing the particular temperature of reaction, caramelization

(the decomposition via dehydration of sugar molecules such as sucrose) is relatively

simple, at least by comparison. Pure sucrose melts at 367°F / 186°C; decomposition begins

at lower temperatures (somewhere in the range of 320–340°F / 160–170°C) and continues up

until around 390°F / 199°C. (Melting is not the same thing as decomposition—sucrose has a

distinct melting point, which can be used as a clever way of calibrating your oven.

Like the Maillard reaction, caramelization results in hundreds of compounds being

generated as a sugar decomposes, and these new compounds result in both browning and the

generation of enjoyable aromas in foods such as baked goods, coffee, and roasted nuts. For

some foods, these aromas, as wonderful as they might be, can overpower or interfere with

the flavors brought by the ingredients, such as in a light gingersnap cookie or a brownie.

For this reason, some baked goods are cooked at 350°F / 177°C or even 325°F / 163°C so

that they don’t see much caramelization, while other foods are cooked at 375°F / 191°C or

higher to facilitate it.

When cooking, ask yourself if what you are cooking is something that you want to have

caramelize, and if so, set your oven to at least 375°F / 191°C. If you’re finding that

your food isn’t coming out browned, it’s possible that your oven is running too cold. If

items that shouldn’t be turning brown are coming out overdone, your oven is probably too

hot.

Fructose, a simpler form of sugar found in fruit and honey, caramelizes at a lower

temperature than sucrose, starting around 230°F / 110°C. If you have other constraints on

baking temperature (say, water content in the dough prevents it from reaching a higher

temperature), you can add honey to the recipe. This will result in a browner product,

because the largest chemical component in honey is fructose (~40% by weight; glucose comes

in second at ~30%).

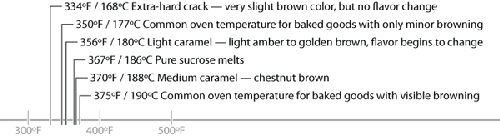

Temperatures related to sucrose caramelization and

baking.

Here’s an easy experiment to do with kids (or on your own),

and regardless of the results, the data is delicious! Since sugar caramelizes in a

relatively narrow temperature range, foods cooked below that temperature won’t

caramelize. Thus, when making sugar cookies, you can determine whether they will come

out a light or dark brown. Try cooking four batches of sugar cookies at 325°F, 350°F, 375°F, and 400°F (163°C,

177°C, 190°C, and 204°C). Those cooked below the 356–370°F / 180–188°C range will remain

light-colored, and those cooked at a temperature above sucrose’s caramelization point

will turn a darker brown. It’s nice when science and reality line up! This isn’t to say hotter cooking temperatures make for better

results than cooler ones. It’s a matter of personal preference. If you’re like some of

my friends, you may think sugar cookies are “supposed” to be light brown and chewy,

maybe because that’s the way your mom made them when you were growing up. Or maybe you

like them a bit browner on the outside, like a rich pound cake. Note that the flour used in sugar cookies contains some amount of proteins, and

those proteins will undergo Maillard reactions, so cookies baked at 325°F / 163°C and

350°F / 177°C will develop some amount of brownness independent of

caramelization.

Cross-section (top piece) and top-down (bottom piece) views of sugar

cookies baked at various temperatures. The cookies baked at 350°F / 177°C and

lower remain lighter in color because sucrose begins to shift color as it

caramelizes at a temperature slightly higher than 350°F / 177°C.

|

Goods baked at 325–350°F / 163–177°C

|

Goods baked at 375°F / 191°C and higher

|

|---|

|

Brownies

|

Sugar cookies

| |

Chocolate chip cookies (chewy)

|

Peanut butter cookies

| |

Sugary breads: banana bread, pumpkin bread, zucchini bread

|

Chocolate chip cookies

Flour and corn breads

| |

Cakes: carrot cake, chocolate cake

|

Muffins

|

Temperatures of common baked goods, divided into those below and above

the temperature at which sucrose begins to visibly brown.

|

Caramel sauce is one of those

components that seems complicated and mysterious until you make it, at which point

you’re left wondering, “Really, that’s it?” Next time you’re eating a bowl of ice

cream, serving poached pears, or looking for a topping for brownies or cheesecake, try

making your own.

Traditional methods for making caramel sauce involve starting with water,

sugar, and sometimes corn syrup as a way of preventing sugar crystal formation. This

method is necessary if you are making a sugar syrup below the melting point of pure

sucrose, but if you are making a medium-brown caramel sauce—above the melting point of

sucrose—you can entirely skip the candy thermometer, water, and corn syrup and take a

shortcut by just melting the sugar by itself.

In a skillet or large pan over medium-high heat, heat:

1 cup (240g) granulated sugar

Keep an eye on the sugar until it begins to melt, at which point turn your burner

down to low heat. Once the outer portions have melted and begin to turn brown, use a

wooden spoon to stir the unmelted and melted portions together to distribute the heat

more evenly and to avoid burning the hotter portions.

Once all the sugar is melted, slowly add while stirring or whisking to

combine:

1 cup (240g) heavy cream

Notes

This thing is a calorie bomb: 1,589 calories between the cup of heavy

cream and cup of sugar. It’s good, though!

Some recipes call for adding corn syrup to the sugar as you heat it.

This is because the sucrose molecules, which have a crystalline structure, can

form large crystals and chunk up in the process of heating. The corn syrup

inhibits this. If you heat the plain sugar with a watchful eye and don’t stir it

until it gets hot enough, the corn syrup isn’t necessary. (It would be necessary,

however, if you were only heating the sugar to lower temperatures—temperatures

below the melting point—for other kinds of candy making.)

Try adding a pinch of salt or a dash of vanilla extract or lemon juice

to the resulting caramel sauce.

Different temperature points in the decomposition range yield

different flavor compounds. For a more complex flavor, try making two batches of

caramel sauce, one in which the sugar has just barely melted and a second where

the caramel sauce is allowed to brown a bit more. The two batches will have

distinctly different flavors; mixing them together (once cooled) will result in a

fuller, more complex flavor.

Sucrose has a high latent heat—that is, the sugar molecule is able to

move and wiggle in many different directions. Because of this, sucrose gives off

much more energy when going through the phase transition from liquid to a solid,

so it will burn you much, much worse than many other things in the kitchen at the

same temperature range. There’s a reason pastry chefs call this stuff “liquid

Napalm.”