A river flows across it

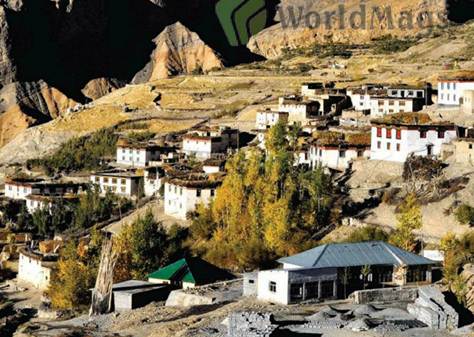

Above the left bank of Spiti River, in the

shadow of Himalaya’s rain, lies a beautiful and peaceful land. Covered with

snow within 6 months, with temperature falling under -25 degrees Celsius, this

highland becomes alive in such a short summer. The winter’s white blanket has

melt to reveal a verdant green which slowly turns into orange then ochre of the

autumn. Hardened hands are working on field full of green peas and wheat; yaks

and dzopkyos (hybrids of cow and yak) are wandering on pastures spotted with primulas

and anemones. In last September, we did walk along the riverside for 4 days and

enjoy significant views as well as gorgeous colors that only nature can bring.

Day 1

My companions, Paula and Sisi, travelled

from Lhangza to Komic on an autumn morning with Chau Chau Kang Nilda peak (6,303m)

left behind. The mountain was first challenged by Jimmy Roberts in 1939 and

again by Trevor Braham and Peter Holmes in 1955. Lhangza villagers believed

that bad weather would go after a successful climbing – thus they didn’t encourage

people to climb this mountain.

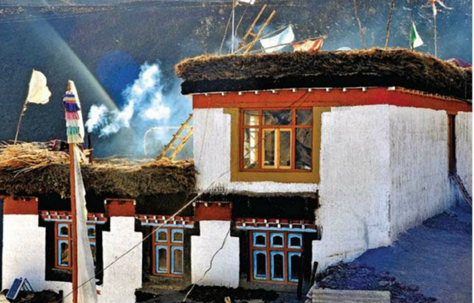

When we climbed down from the monastery, we

came across donkeys carrying goods and returning to home from the center of Kaza

district. Roof-tops were filled with hay for winter months.

We

came across donkeys carrying goods and returning to home from the center of

Kaza district.

Praying people’s flags, stones and horns of

ibexes or blue sheep beautified the trail (4,400m) above Hikim village. From

there, the trail plunged down into the village then headed to Komic monastery situated

on a sheer hill. This was the only visited monastery that didn’t let women in the

main prayer hall.

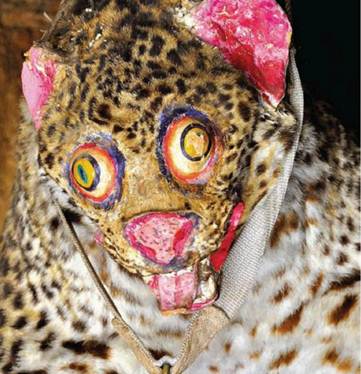

At Komic’s entrance lay a stuff snow

leopard which was confirmed by lamas to have been found dead around the

village.

At

Komic’s entrance lays a stuff snow leopard.

We

unexpectedly saw an abandoned house’s interesting remnants in the late

afternoon.

Day 2

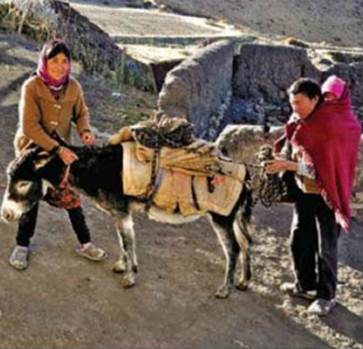

Our morning started with that our guide,

Kunga Chorden, served us breakfast in his kitchen at Komic village. Meanwhile, his

parents were harnessing a donkey to visit a market at Kaza.

His

parents were harnessing a donkey to visit a market at Kaza.

On way down, we met a friendly herdsman riding

his yak to Demul village. His sheep and goats were grazing in far pastures.

Yaks, sheep and goats play an important role of villagers’ earning for living. Yak

cheese, butter and milk are used daily for home cooking when yak meat is special

food for festivals. Yak wool is used to make tents, blankets and carpets.

We

met a friendly herdsman riding his yak to Demul village.

Paula left the only path (4,700m) of Yang

Lapzey and headed towards Demul village. Kamelang peak, in Lingti valley’s

eastern side, emerged from the sky.

Approaching Chamay Lapzey’s only path, we

passed a partly-frozen stream. Water was still a rare resource in grass land

for cattle and there were every few streams to support villages.

Water

was still a rare resource in grass land for cattle.

Day 3

Homestay at Demul was interesting. The

village’s house are renovated and equipped with lights powered by solar energy.

Homestay

at Demul was interesting.

Dolma

and our guide Kunga prepared dinner in a cozy kitchen of Khabrick Homestay at

Lhalung.

After a long exhausting trip – because the

bridge below Lhalung village had collapsed – the sunny village welcomed us. Viewing

from Lhalung, on a sheer hill, we saw the gorgeous Sharkhang monastery.

The

gorgeous Sharkhang monastery

Day 4

Dhangkar monastery, around the last bend, showed

itself dramatically, embraced by spiky peaks covered with snow. From its

roof-top, we could see Spiti river’s blue veins winding through the valley.

We

could see Spiti river’s blue veins.

On way to Dhangkar, we met a herd of unruly

ibexes. Ashamed and quite, they ran away when we, with our cameras, were

approaching. Ibexes are main preys of snow leopards that are found around villages

in winter months.

Ibexes

are main preys of snow leopards.