Welcome to an enchanting land of golden

pagodas, velvet shoes and lotus flowers. After decades of darkness and fear,

the horizon is full of hope as visitors are being encouraged to explore the

treasures this unique Asian country once more, says Harriet O’ Brien.

Land of the Golden Pagodas

Early one morning I watched a farmer propelling a small piece of land across a lake.

Around him jet-black cormorants and sharp-white egrets fished the still waters.

On the misty shores behind, golden pagodas glinted from the tops of forested

hills it was a staggeringly beautiful scene.

It was surreal, too. The farmer was taking

his plot to a floating nursery garden where the enterprising locals grow

tomatoes, cauliflowers, beans and other crops. Cleverly created out of water

hyacinths and silt, these lush little rafts (like island-allotments) are

anchored together in a large plantation and tended from narrow longboats.

The serenity of the watery scene before me

was shattered as a motorized longboat sped into view. It was filled with

Burmese tourists who waved and cheered at me and the farmer. Then they zoomed

out of sight. They left a wake of joy that was shortly augmented by another

boat of happy, waving Burmese visitors. Like so much else in this extraordinary

country, the floating world of Inle Lake was utterly enchanting.

the

floating world of Inle Lake was utterly enchanting

Burma is an almost fairy-tale land of

exquisite idiosyncrasies, The people wear velvet flip- flops; men and women are

almost always impeccably turned out in skirt-like lungyis (roughly pronounced

‘lunegee’ – the weird romanised spelling of Burmese words reflects the fact

that certain sounds simply don’t exist in the West); and they liberally and

devoutly apply small patches of gold leaf to their already gilded temples and

golden images of Buddha – it is a great act of reverence to do so. In the

meantime, their myriad pagodas hum with the sounds of gongs and bells, which

are struck every time a donation is made so that all may share the merit of the

good deed. The reverberating spirit of generosity is part of the innate charm

of the Burmese people and their culture.

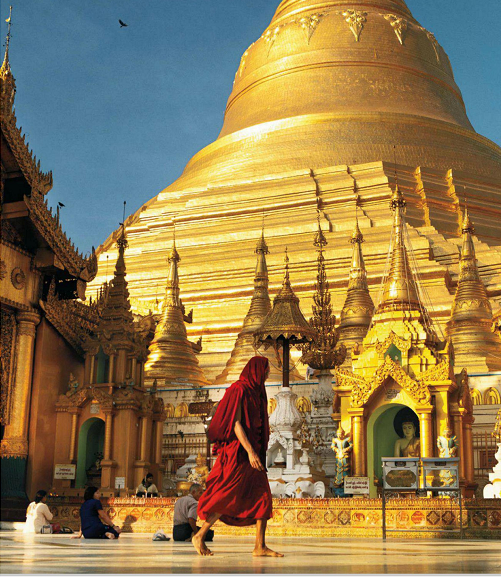

Shwedagon

Pagoda in Rangoon

Yet, as in many stories of enchantment,

there is a distinctly sinister element. Over the past 50 years Burma has, of

course, become a byword for political prisoners and military oppression.

Although it was renamed Myanmar in 1989, many Western states ignored the change

and continue to refer to the country as Burma: it is, in effect, a mark of

defiance against the brutal regime, most notably on the part of the UK and USA.

However, that defiant stance is being

cautiously softened. Most observers agree that real liberalizing reform appears

to be taking place, particularly given the results of the recent by-elections.

These, of course, saw the remarkable opposition leader, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi,

elected to parliament for the first time. On my visit a few months earlier

there was a mood of tremendous optimism: many people I spoke to were openly

rapturous about the prospect of genuine democracy.

“In

the village of in paw khon I watched silk and cotton fabric taking form, then

gazed spellbound as fibre was created, as if by magic, out of lotus plants”

Burma wasn’t new to me, but the joy there

was. In the 1970s my parents lived in the then capital, Rangoon (renamed Yangon

in 1989), and on visits from school in Britain the city was my home. It was a

little over 25 years after the end of British rule in Burma, and we were among

a small number of foreigners in the country, almost all diplomats or UN

officials and their families. Tourism was not encouraged, and visas were very

circumscribed.