As in other parts of Burma, visitors are

welcome at the local pagodas and monasteries. Indeed, part of the charm of any

trip to the country is the inclusiveness of the form of Buddhism practiced

there and the fact that today you often join happy groups of Burmese travelling

to these religious sites from far afield – such freedom of movement being a far

cry from my previous experiences of Burma. Jostling cheerfully among crowds of

elegant longboats, we felt as if we had strayed into an exotic Canaletto painting

as we moored by Phaung Daw Oo Pagoda. A long with the flotilla of an extended

Burmese family, we moved on to Nga Hpe Monastery. The ingenious monks at this

beautiful, wood-carved complex have managed to teach their resident cats to

jump through hoops on command; the third generation of such felines is now in

training, I was told. We jointed another large group of Burmese tourists

applauding a bizarre display by a couple of fat and otherwise snoozy tabbies,

their show resonating with the gently wacky character of the Intha people.

Burmese woman with thanaka on her face

Early the next day, our boat took us down

narrow channels festooned with kingfishers to the village of Indein. We had

come to see the pagoda complex, and particularly an amazing host of half-ruined

outlying stupas. Invasive vegetation has added fantastical drama to their

crumbling romance, with banyan trees having taken root in the brickwork here

and there, while elsewhere creepers are making a march on finely worked 17th-century

stucco decoration. Feeling like Indiana Jones, we scrambled through the

undergrowth to see intricate murals, beautifully rendered archways of mythical

birds, and even, inside one stupa, a golden Buddha sitting in rubble. Catch it

all while you can, said out guide. The Indein complex certainly needs rescuing,

but the worry is that conservation will be swept aside by development. Inle

Lake, he added, is changing very fast – thanks to tourism.

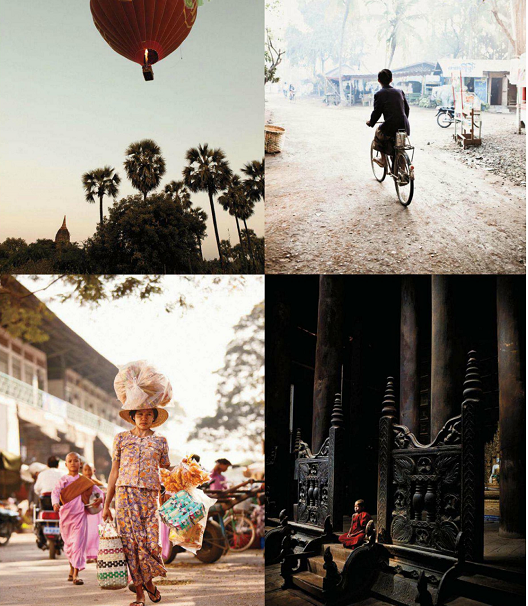

A

hot-air balloon over the area; the village surrounding Shinpin Shwe Gu Gyi

Pagoda; a young monk in Bagaya Monastery, Inwa; 86th Street Market,

Mandalay

We flew on to Mandalay that evening and

were staggered by the size of its airport, constructed in the late 1990s. Only

about a third of the vast arrivals hall was in use. Clearly it was built with

millions more visitors in mind.

Mandalay was the last capital of the

Burmese kings before the British took full control of the country in 1885. In

my youth it was a dusty place of house-drawn carts, low-level industry and many

monasteries. Thanks to Chinese investment, today it is booming. Yet it remains

a low-rise city and retains a village-like atmosphere. As a manifestation of

modern Burma, it is an absorbing place to visit because it is so go-ahead yet

so traditional. We wandered through the huge and buzzing market; we called in

at a couple of jade shops where great wads of money were changing hands between

Chinese traders; we visited a gold-leaf manufacture. Mandalay is the country’s

major centre for gold-leaf production. The wafer-thin strips of precious metal

are pounded by hand entirely to serve the religious needs of an ever-demanding

domestic market.

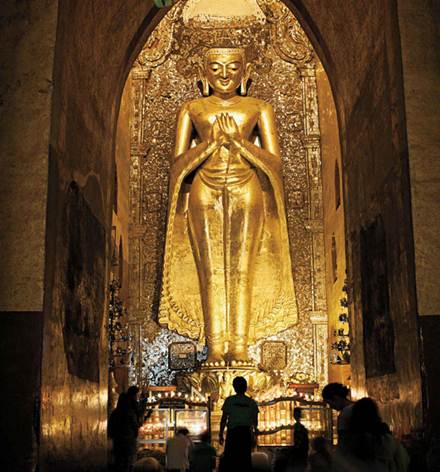

A

Buddha statue inside Ananda Temple in Bagan

As Mandalay’s 19th-century

palace was severely bombed during World War II, large sights are limited.

Tourists are taken to the carved-teak Golden Palace Monastery (Shwenandaw), the

only surviving building of the royal complex; to the serene Kuthodaw Pagoda,

where 729 huge marble slabs are inscribed with the text of the Tripitaka, the sacred

scripts of Theravada Buddhism; to the Mahamuni Pagoda, where one of Burma’s

most venerated Buddha images is housed – it is 3.8 metres high and so coated in

gold leaf that its body shape is becoming a blod. And perhaps the most famous

sight is 240-metre Mandalay Hill, where visitors climb covered stairways lined

with stalls and iconic images, timing their trip to the top to coincide with

sunset over the city and the great Irrawaddy River.

the

top to coincide with sunset over the city and the great Irrawaddy River