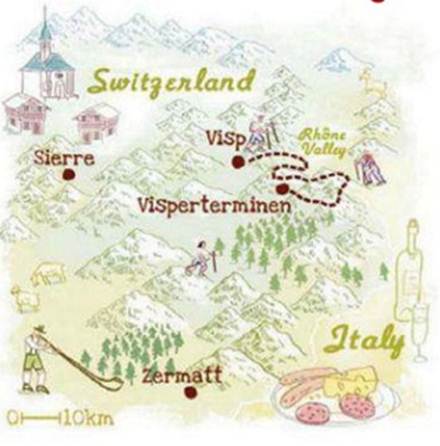

William Cook joins revelers on an annual hike through

vineyards above the Rhône Valley.

Every year, on the first Saturday in September, the

inhabitants of Visp, a sleepy Swiss town near Sierre in the Rhône Valley, stage

the world’s most scenic pub crawl. This isn’t a drunken stagger down the high

street; for the Swiss, that would be far too easy. Instead, participants take

to the hills, climbing 500 metres in few hours, stopping at half a dozen points

en route to enjoy the view and eat lots of food washed down with copious

quantities of the local wine.

The inhabitants of

Visp, a sleepy Swiss town near Sierre in the Rhône Valley, stage the world’s

most scenic pub crawl

It sounded mad: if there are two things that don’t mix, I

thought, it’s Alps and alcohol. In Britain such a perilous lark would surely

result in falls, fist fights and frostbite. But, being Swiss, the men and women

of Visp conduct this piss-up very properly. I still can’t quite believe I

completed the course, and I doubt I could repeat it: but somehow this

Bacchanalian escapade passed off almost without a hitch. Here’s what happened-

at least as far as I can recall.

We met in Visp at 9am, in the quaint old market square. I’d

expected a kitsch spectacle with alpenhorns and lederhosen, but the place was

throbbing with rock music (Guns N’ Roses, among other bands) and the streets

were peopled with athletic types kitted out in state-of-the-art hiking gear. My

old anorak and walking boots looked amateurish by comparison.

There were three in our party: me, Boris (the German

photographer) and Rafaela (our Swiss guide). I was all for wandering off to get

a bit of breakfast, but Rafaela said we had to complete our registration.

Registration? For a pub crawl? This wasn’t a pub crawl, she explained: It was

the annual Wii-Grill-Fascht, a great day out with all you can eat and drink

along the way for SFr90 (about $90).

the altitude of

its vineyards, which rise from 650 metres to a vertiginous 1,150 metres, among

the highest in Europe

I had hoped to hear some romantic stuff about the

Wii-Grill-Fascht’s archaic origins, but it actually only dates back to

1994,when the locals stole the idea from an Italian town across the border.

Never mind, Visp’s event has one thing the Italians could not match, and that’s

the altitude of its vineyards, which rise from 650 metres to a vertiginous

1,150 metres, among the highest in Europe. ‘How on earth do they grow grapes at

such a height?’ I asked Rafaela, as we queued up for our complimentary wine

glasses. She said something about this valley being a climatic hotspot. Yet

surely there are similar hotspots elsewhere that don’t have vines? No, reckon

the Swiss make wine up here for the same reason they built their mountain

railways: because of their quiet determination to achieve things that less

ingenious nations would consider complete daft.

our first

rendezvous at 696 metres

After half an hour Visp’s square was full of people, and at

9.30am sharp (as stipulated in our itinerary) we set off, proceeding at brisk

pace to our first rendezvous at 696 metres, where smiling women dispensed

platters of cheese and wine from a marquee. You carry wine glass in little

canvas pouch around your neck, and whenever you stop, someone is always on hand

to fill it up.

We continued uphill, through vertiginous vineyards on the

rocky hillsides, to our second pit stop, at 855 metres, where more smiling

women handed out more wine and cheese, plus sausage and salami. Unsuitable for

teetotalers, this was no trek for vegetarians, either.

Winemaking in Switzerland began in Roman times, and was

continued by monks through the Middle Ages. The quality of the product is

consistently good, and occasionally outstanding; yet no one outside the country

seems to know much about Swiss wine. This is because the Swiss drink most of it

themselves.

As you might expect in such a mountainous country, the

amount they can make is tiny- about 0.5 per cent of world production. (France

and Italy each produce about 15 per cent). Less than 15,000 hectares are under

vine, and once the Swiss have drunk their fill there’s not much left for

export. Yet the odd bottle finds its way into Continental restaurants, and the

country’s wine now enjoys something of an international reputation especially

the light, crisp whites. If you’re bored of boozy New World plunk,

Switzerland’s offerings are a revelation- delicate and refreshing, ideal for

lunchtime drinking or with some of that tangy cheese. In particular, look out

for Chasselas, a subtle white grape that’s especially popular here, yet little grown

elsewhere.

At our third stop

(907 metres)

Of those 15,000 hectares of vines, more than 5,000 are here

in Valais, Switzerland’s main winemaking canton. Most of the vineyards are

tiny, less than 500 square metres on average; and the wines show a remarkable

variety from village to village. Surprisingly, at such high altitudes, 40 per

cent of production is red, mainly Pinot Noir and Gamay.

We walked onward and upward to our third stop (907 metres),

for a bowl of stew and yet more vino. By now things were becoming a bit blurry.

I’d already sampled the Chasselas and Heida, an the Riesling and Sylvaner, and

it was still morning. A brass band in traditional dress was playing traditional

Alpine music. I could see the bright-red carriages of the Glacier Express, a

little toy train weaving through the river valley far below. There were

hundreds of hikers ahead of us and thousands more behind, all following the

same hopscotch path. The sound of thei shared laughter echoed all around us. I

had to force myself to walk on. I wanted to lie down and go to sleep. Older

people, fatter people: everyone was overtaking me. Did they do this every

weekend? The sun was fierce and the heat was stifling. It was a relief when the

path dropped down into a wooded valley. Trying to sober up, I washed my face in

a mountain stream. The water my face in a mountain stream. The water was

ice-cold.

By now Boris was miles behind, taking photographs of tipsy

hikers; and while we waited for him to catch up, Rafaela told me a bit about

her life. She grew up in these mountains, in the village where our trek would

end, and at our fourth stop (963 metres) we met her husband, working in one of

the refreshment tents. He grew up here too, and though they’d spent a few years

abroad, on the west coast of Ireland, they always knew they’d return. The Swiss

have a special word for it: heimat. It means a sense of home.

At our fifth stop

(1,045 metres)

At our fifth stop (1,045 metres) there was some

creamy potato salad and a rich Pinot Noir. We sat down and a rich Pinot Noir.

We sat down and admired the view, marveling at how far we’d come. As we did so,

a dozen hikers formed a semicircle and began to yodel, and I realized how this

music was made for these mountains, and how here it is the most beautiful music

in the world. When they had finished I was surprised to find that my cheeks

were wet with tears.

I was grateful for the soft descent to an ancient farmyard,

for the kaffee und kuchen (coffee an cake) we ate and for the shade of an old

barn – but not for the shot of schnapps, the last thing I needed. Mercifully,

it was then just a short stroll to Rafaela’s village, Visperterminen, where a

raucous street party had begun.

It was now teatime and I already had a hangover, yet all

around me my fellow hikers were buying drinks and bopping along to cheesy

Europop in the village square. I bought a beet and then another, but it was no

use – I’d drunk myself sober, ‘I feel terrible’, I told Boris. ‘If I don’t find

somewhere to lie down I think I may fall over.’ ‘Don’t worry’, he said. ‘You’ve

got the story. Get some sleep’. He was fine. He hadn’t had a drink all day.

I staggered off to find the bus- which arrived bang on time,

of course. As we descended into Visp, people were still striding uphill to join

the party. Boris called me later to say that the evening had ended with a

thunderstorm and a scuffle.

My head still hurts. My tongue feels like sandpaper. I can’t

wait to go back again next year.