Ethnic Burmese account for more than two-thirds of the country’s 56 million people. A

bewildering number of other groups make up the remaining third (from the Atsi

to the Wa and the Zo, some say there are 100, others say it’s more like 200).

Most of these minorities want independence from the central government or

federalism. Self-determination is such an impassioned issue that many have

their own armies. Indeed, it was initially because of internal warfare that the

Burmese army because so powerful. A number of ceasefires with rebel groups have

been holding since about the end of the 1990s, but there is still conflict in

some areas – which are out of bounds to tourists – and more recently there have

been reports of truces being broken in several previously peaceful places.

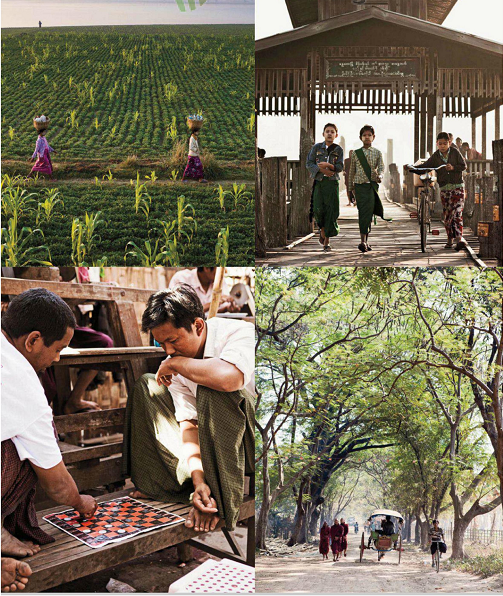

Fields

near Taungthaman Lake; the entrance to U Bein Bridge; the road to Bagaya

Monastery, Inwa; downtime at a jade market in Mandalay

There have, however, been no reports of

conflict in Kalaw and the surrounding region. That’s because of the Burmese

soldiers there and the new tourist money coming in: the town is gently

developing as a base for trekking. After a night in a spick-and-span guesthouse

that had opened a few months previously, we set out with a guide on a day’s

excursion. Following a red-mud track from the edge of town, we entered a land

of abundance. This was plantation country, producing coffee, tea, fruit and

vegetables. Enormous butterflies flitted by winding streams as we walked

through great groves of oranges and preposterously large lemons. A civet cat

bounded up a hill past rows of aubergines as we reached the outskirts of a

Palaung village, where we stopped for cups of green tea and admired the local

weaving. We continued over dramatic hills and through more Palaung villages

before reaching the road where our car was waiting.

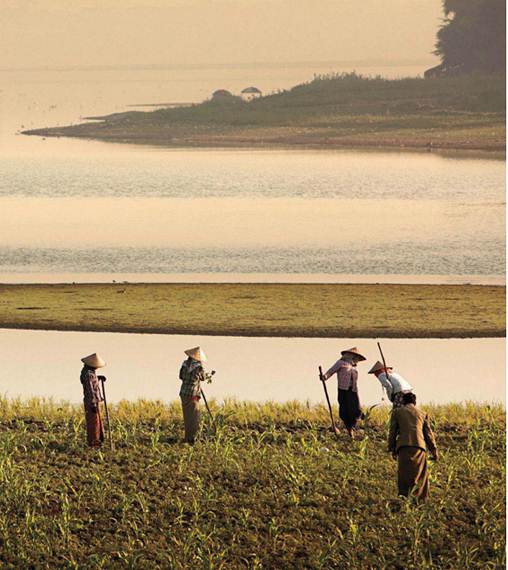

Working

the fields on the shores of Taungthaman Lake

Inle Lake, about three hours’ drive east, was our next port of call. On arriving in the area, we took a

brief detour to see another plantation: one of Burma’s first vineyards. Set

near the cheerful little town of Nyaung Shwe, Red Mountain Estate is largely

the creation of resident French winemaker Francois Raynal, who started playing

here in 2003. Sounds unlikely? Well, yes, but the results are very drinkable,

particularly the Sauvignon Blanc. We explored the winery in a daze, looking out

to distant pagodas over neat rows of vines. Then we proceeded to the lake

itself.

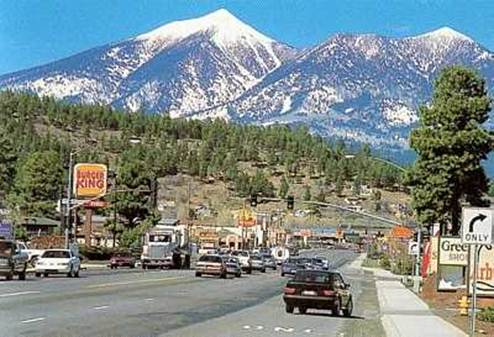

Red

Mountain Estate

Just over 13 miles long, this body of water

presents some of Burma’s most dreamy scenery – and some of its most wonderfully

quirky sights. The indigenous Intha people live over the water in houses on

stilts. They grew wealthy (by Burmese standards) from farming their homemade

floating islands and from fishing, for which they developed a curious method of

rowing with one arm and a leg so as to keep the other arm free for manoeuvring

nets. They now also make tidy sums from tourism. Visitors are taken around the

lake by motorized longboat, their picturesque tours punctuated by plenty of

retail opportunities, with stops at teak-panelled workshops on stilts:

silversmith, cheroot-maker, papermaker. Most striking of all is the weaving

outfit at the village of In Paw Khon. Here you step into a world of wooden

looms, all worked by hand. I watched silk and cotton fabric taking form, then

gazed spellbound as fibre was created, as if by magic, out of lotus plants. The

stems are twisted to extract sap which is then rubbed into long strings of a

silk-like substance. Once spun, this produces a delicate material of such

quality that the Italian label Loro Piana introduced lotus-fibre pieces in its

2011 collection.

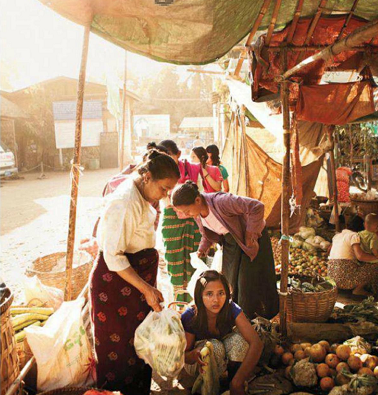

Nyaung

U Market in Bagan