|

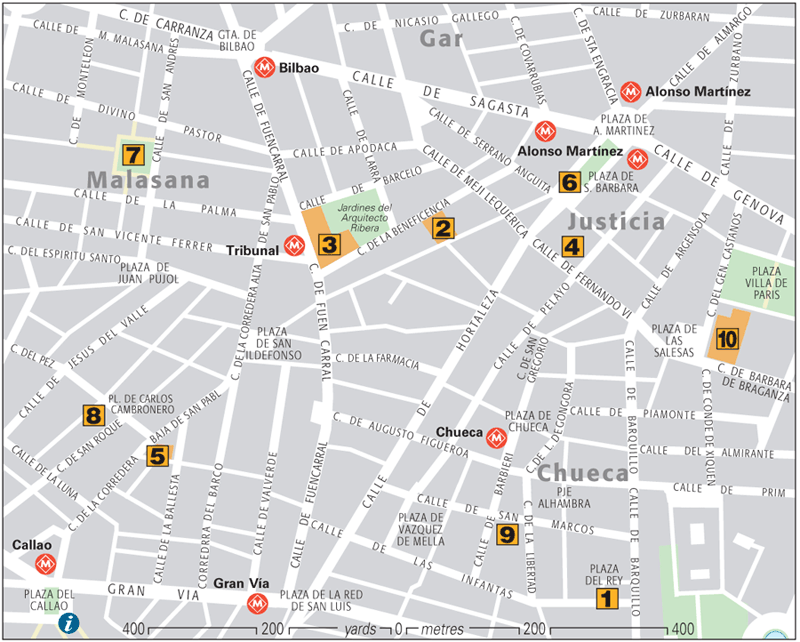

Two of Madrid’s most lively

barrios lie just off the Gran Vía. Chueca was originally home to the

city’s blacksmiths and tile makers. Run down for many years, it has

enjoyed a renaissance after being adopted by Madrid’s gay community –

the area puts on its glad rags every summer for the Gay Pride

celebrations. The 19th-century buildings around Plaza de Chueca have

been given a new lease of life as trendy bars and restaurants.

Neighbouring Malasaña was the focus of resistance against the French in

1808. Like Chueca, it became rather seedy, but is now a mainstay of

Madrid nightlife.

|

The seamstress, who became a national heroine

following the 1808 uprising, was still a teenager on that fateful day in

May, when, so the story goes, she was approached by a couple of French

soldiers. Despite her protestations, they insisted on conducting a body

search, provoking her to stab at them with a pair of dressmaking

scissors. They shot her dead, but her memory lives on in the district

which now bears her name.

|

SightsCasa de las Siete Chimeneas The

“house of the seven chimneys” dates from around 1570 and is one of the

best preserved examples of domestic architecture in Madrid. The building

is said to be haunted by a former lover of Felipe II – not as far

fetched as it sounds, as a female skeleton was uncovered here at the end

of the 19th century. The house later belonged to Carlos III’s chief

minister, the Marqués de Esquilache, whose attempts to outlaw the

traditional gentleman’s cape and broad brimmed hat, on the grounds that

rogues used one to conceal weapons and the other to hide their faces,

provoked a riot and his dismissal. Plaza del Rey 1 Closed to the public

Museo Romántico This

unusual but evocative museum, as its name suggests, recreates the

Madrid of the Romantic era (c.1820–60), with rooms furnished and

decorated in the style of the period. The real attraction, however, lies

in the ephemera: fans, figurines, dolls, old photograph albums, cigar

cases, visiting cards and the like, which all help to summarize the era.

Among the paintings is a magnificent Goya in the chapel and a portrait

of the Marqués de Vega-Inclán, whose personal possessions form the basis

of the collection. By common consent, the archetypal Spanish Romantic

was Mariano José de Larra, a journalist with a caustic pen, who shot

himself in 1837 after his lover ran off with another man. The offending

pistol is one of the museum’s prized exhibits.

Museo Romántico

Museo de Historia This

former poorhouse is now a museum tracing the history of the capital

from the earliest times to the present day. Prize exhibits include

mosaic fragments from a local Roman villa, pottery from the time of the

Muslim occupation, a bust of Felipe II, and Goya’s Allegory of the City of Madrid (Dos de Mayo).

The star attraction is a wooden model of the city, made in 1830 by León

Gil de Palacio. As you leave, take a look at the elaborately sculpted

Baroque portal, dating from the 1720s. Calle de Fuencarral 78 Open 9:30am–8pm Tue–Fri (to 2:30pm in Aug), 10am-2pm Sat–Sun Some areas closed for refurbishment until 2010 Free

Palacio Longoria The

finest example of Art Nouveau architecture in Madrid was created for

the banker Javier González Longoria in 1902. The architect was José

Grases Riera, a disciple of Antoni Gaudí. Magnificently restored in the

1990s, the walls, windows and balconies are covered with luxuriant

decoration suggesting plants, flowers and tree roots . Calle de Fernando VI, 8 Closed to public

Iglesia de San Antonio de los Alemanes The

entire surface area of this magnificent domed church is covered with

17th-century frescoes depicting scenes from the life of St Anthony of

Padua. The congregation included the sick and indigent residents of the

adjoining hospice, who were allocated a daily ration of bread and boiled

eggs. (The church still has a soup kitchen). Calle de Fuencarral This

narrow street, permanently clogged with traffic, is worth negotiating

for its original and offbeat shops. High street fashions are represented

by outlets such as Mango (No. 9) but for something more outré,

check out the party fashions at No. 47, or the seductive underwear at

Chocolate (No. 20). La Reserva (No. 64) sells silver jewellery handmade

by Navajo Indians, as well as Mexican belts and snakeskin wallets. Café

Po zo (No. 53) offers its own blends of coffee and tea, while Retoque

(No. 49), founded in 1920, goes in for picture frames and modern art

posters.

Calle de Fuencarral

Plaza del Dos de Mayo This

square in the heart of Malasaña commemorates the leaders of the

insurrection of May 1808, Luis Daoíz and Pedro Velarde, who are buried

in the Plaza de Lealtad.

The site was chosen because, in those days, this was the artillery

barracks of the Monteleón Palace, the main focus of resistance to the

French. The brick arch now sheltering a sculpture of the two heroes was

the entrance to the building. In the 1990s the square was taken over by

under-age drinkers who gathered here at weekends for binges known as botellón. Though it has now been reclaimed by local residents, it is best avoided at night. Iglesia San Plácido Founded

in 1622 by Don Jerónimo de Villanueva, a Madrid nobleman, the early

history of this convent was darkened by scandal. Rumours of sexual

misconduct among the novices led to an investigation by the Inquisition

which implicated the chaplain, the abbess and the Don himself. It was

even rumoured that Felipe IV made nocturnal visits to the convent via a

passageway under the street. Today the main attraction is the splendid

Baroque church (1655). The retable over the altar contains a magnificent

Annunciation by Claudio Coello. Calle S Roque 9 Open for services Free

Iglesia San Plácido

Hotel Mónaco At

the turn of the 20th century the Mónaco was a well known brothel

frequented by members of the Spanish nobility including, so rumour has

it, King Alfonso XIII. Now a respectable hotel, the breakfast room

retains some of the original features, such as the leather booths, while

the rest has been redecorated in Art Deco style .

Hotel Mónaco

Iglesia de las Salesas Reales The

monastery of the Royal Salesians was founded by the wife of Fernando

VI, as a refuge from her overbearing mother-in-law should the king die

before her (in fact, she died first). You can still see the lavish

Baroque church (1750), sculptures and decorative details on the façade

and the tombs of Fernando and his wife by Francesco Gutiérrez.

Iglesia de las Salesas Reales

|