This is Baroque Rome in all

its Theatrical Glory, a collection of curvaceous architecture and

elaborate fountains by the era’s two greatest architects, Bernini and

Borromini, and churches filled with paintings by the likes of Caravaggio

and Rubens. The street plan was largely overhauled by 16th- to

18th-century popes attempting to improve the traffic flow from St

Peter’s – in fact, a 19th-century plan to turn Piazza Navona into a

boulevard from Prati across Ponte Umberto I was only killed when wiser

heads widened Corso del Rinascimento instead. However, ancient Rome does

peek through in the shape of Piazza Navona and the curve of Palazzo

Massimo alle Colonne. This is also a neighbourhood of craftsmen,

shopkeepers and antiques restorers and dealers who line Via dei Coronari

(see Antiques Shops).

More recently the narrow alleys around Via della Pace have become a

centre of Roman nightlife, with tiny pubs, trendy cafés and nightspots

where the clientele spills out into the streets in summer (see Chic Cafés and Bars).

|

During the Renaissance, the most strident voices against political scandal and papal excess came from statues. Rome’s statue parlanti

“spoke” through plaques hung around their necks by anonymous wags

(although Pasquino was known to be a local barber). Pasquino’s

colleagues included Marforio , Babuino on Via del Babuino and “Madama Lucrezia” on Piazza San Marco.

|

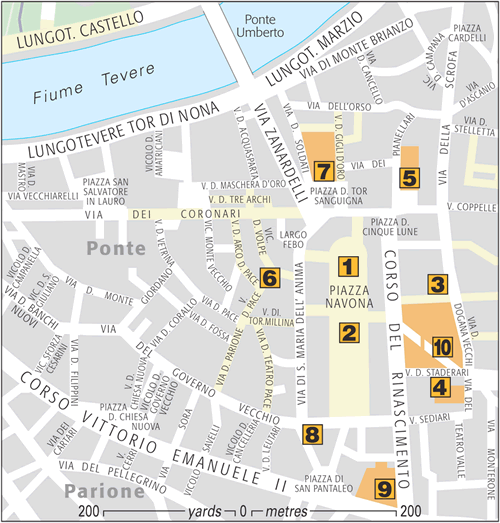

SightsPiazza Navona One of Rome’s loveliest pedestrian squares

is studded with fountains and lined with palaces, such as the Pamphilj,

the church of Sant’Agnese, and classy cafés such as Tre Scalini (see Tre Scalini).

Piazza Navona

Piazza Navona

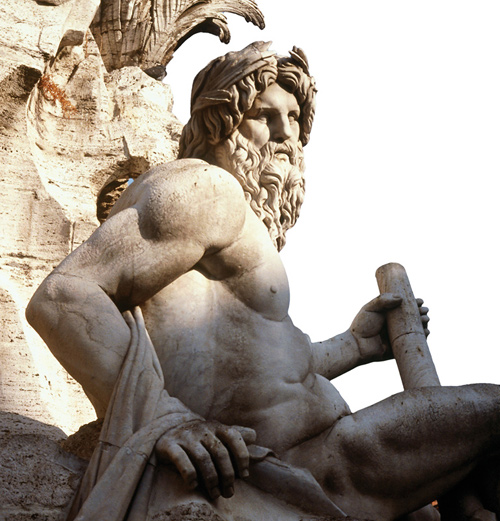

Four Rivers Fountain The

statues ringing Bernini’s theatrical 1651 centrepiece symbolize four

rivers representing the continents: the Ganges (Asia, relaxing), Danube

(Europe, turning to steady the obelisk), Rio de la Plata (the Americas,

bald and reeling), and the Nile (Africa, whose head is hidden since the

river’s source was then unknown). The obelisk, balancing over a

sculptural void, is a Roman-era fake, its Egyptian granite carved with

the hieroglyphic names of Vespasian, Titus and Domitian.

The Ganges, Four Rivers Fountain

San Luigi dei Francesi France’s

national church in Rome has some damaged Domenichino frescoes (1616–17)

in the second chapel on the right, but everyone bee-lines for the last

chapel on the left, housing three large Caravaggio works. His plebeian,

naturalistic approach often ran foul of Counter-Reformation tastes. In a

“first draft” version of the Angel and St Matthew,

the angel guided the hand of a rough labourer-type saint; the

commissioners made the artist replace it with this more courtly one . Underlying sketches in Martyrdom of St Matthew and Calling of St Matthew show how Caravaggio was moving away from symbolic compositions in favour of more realistic scenes. Sant’Ivo Giacomo

della Porta’s Renaissance façade for the 1303 Palazzo della Sapienza,

the original seat of Rome’s university, hides the city’s most gorgeous

courtyard. The double arcade is closed at the far end by Sant’ Ivo’s

façade, an intricate Borromini interplay of concave and convex curves.

The crowning glory is the spiralling ellipse of the dome. The interior

disappoints despite its Pietro da Cortona altarpiece. When the courtyard

is closed, you can see the dome from Piazza Sant’ Eustachio. Corso Rinascimento 40 Courtyard: open 8am– 8pm Mon–Fri, 9am–noon Sun Church: open 10am–4:30pm Mon– Fri, 10am–1pm Sat, 9am–noon Sun Free

Spire and lantern, Sant’Ivo

Sant’Agostino Raphael

frescoed the prophet Isaiah (1512) on the third pillar on the right,

and Jacopo Sansovino provided the pregnant and venerated Madonna del Parto; but Sant’Agostino’s pride and joy is Caravaggio’s Madonna del Loreto

(1603–1606). The master’s strict realism balked at the tradition of

depicting Mary riding atop her miraculous flying house (which landed in

Loreto). The house is merely suggested by a travertine doorway and

flaking stucco wall where Mary, supporting her overly large Christ

child, is venerated by a pair of scandalously scruffy pilgrims.

Santa Maria della Pace Baccio

Pontelli rebuilt this church for Pope Sixtus IV in 1480–84, but the

lovely and surprising façade (1656–7), its curved portico squeezed into a

tiny piazza, is a Baroque masterpiece by Pietro da Cortona. Raphael’s

first chapel on the right is frescoed with Sibyls (1514) influenced by the then recently unveiled Sistine ceiling .

Peruzzi decorated the chapel across the aisle and Bramante’s first job

in Rome was designing a cloister based on ancient examples. It now hosts

frequent concerts. Palazzo Altemps This

15th-century palace was overhauled in 1585 by Martino Longhi, who is

probably also responsible for the stucco and travertine courtyard

(previously attributed to Antonio da Sangallo the Younger or Peruzzi).

It now makes an excellent home to one wing of the Museo Nazionale

Romano, its frescoed rooms filled with ancient sculptures.

Pasquino That

this faceless, armless statue was part of “Menelaus with the body of

Patroclus” (a Roman copy of a Hellenistic group) is almost irrelevant.

Since this worn fragment took up its post here in 1501, it has been

Rome’s most vocal “Talking Statue”(see The Talking Statues).

Pasquino, Piazza Pasquino

Palazzo Massimo alle Colonne This

masterpiece of Baldassare Peruzzi marks the transition of Roman

architecture from the High Renaissance of Bramante and Sangallo into the

theatrical experiments of Mannerism that would lead up to the Baroque.

The façade is curved for a reason; Peruzzi honoured Neo-Classical

precepts so much he wanted to preserve the arc of the Odeon of Domitian,

a small theatre incorporated into the south end of the emperor’s

stadium .

Palazzo Massimo alle Colonne

Palazzo Madama Based

around the 16th-century Medici Pope Leo X’s Renaissance palace, the

Baroque façade of unpointed brick and bold marble window frames was

added in the 17th century. Since 1870 it’s been the seat of Italy’s

Senate, so public admission is obviously limited.

Stone relief, Palazzo Madama

|