7. Meat Glue: Transglutaminase

One of the more unexpected food additives is transglutaminase, a

protein that has the ability to bond glutamine with compounds such as lysine, both of

which are present in animal tissue. In plain English, transglutaminase is “glue” for

proteins.

Transglutaminase isn’t used to change the texture of foods or to modify sensations of

flavor. Rather, the food industry uses it re-form scrap meats into large pieces

(McNuggets!). You didn’t actually think that gorgeous hunk of ham at the deli counter was

one piece of meat, did you? From the rare boneless pig?

Transglutaminase is also used to thicken milk and yogurts by making their proteins

longer in the same way that adding longer polysaccharides in gelling applications makes

things thicker. Additionally, it is used to firm up pastas, to make breads more elastic

(able to stretch without tearing), and to improve gluten-free breads for those with celiac

disease.

For food hackers, though, the compelling opportunities for transglutaminase reside

primarily in meat-binding applications. Food hackers have, of course, seized the

opportunity to use it to make Frankenstein meats (all in the name of fun). You can “glue”

white fish to red fish, make a turducken (a turkey-duck-chicken dish) that holds together,

and make a heatstable aspic, relying on transglutaminase instead of heat-sensitive

gelatins or aspics.

The recipes that follow will give you some starting ideas, but really the concept of

“meat welding” can apply to any meats that you want to stay together, including fish and

poultry. You can glue scallops together in a long chain, wrap chicken around fillings

(binding the chicken to the other end of itself), and wrap bacon around scallops.

The reaction occurs at room temperature and takes around two hours to set, so plan

ahead. Use about 1% transglutaminase for the total weight of your food. You can sprinkle

it dry on the food item or create a slurry (2 parts water to 1 part transglutaminase) and

brush it onto the surfaces to be glued. Once adhered together, let the join rest for at

least two hours; otherwise, you will shear and break the bonds as they’re setting.

Chicken and steak bonded together with transglutaminase. Mmm, Doublemeat

Palace!

Keep in mind that, because you’re made of protein, you should

take care to not get it on your skin or inhale the powder. Unlike real glue,

transglutaminase is actually a chemical catalyst that literally bonds the two sides

together at a molecular level. Gloves and a respirator mask are good insurance. Since

transglutaminase is a protein itself and has the same structures as the amino acids it

binds, it’s also capable of binding to itself. After a few hours at room temperature,

though, it loses its enzymatic properties, so it’s not a huge deal if you spill a bit on

your work surface. Once opened, store it in your freezer to slow the rate of the binding

reaction.

Instructions for use. Create a slurry of water and

transglutaminase and brush it onto the surfaces that you want to join. Press them

together and wrap with plastic wrap. Store in fridge for two hours or longer.

Note:

Try vacuum-packing the food. This will improve the fit between the two pieces of

meat.

Uses. Protein binder. Used by the food industry to take scraps of meats and form them

into a larger shape, such as deli-style sliced turkey, and to thicken dairy products

such as yogurt.

Origin. Manufactured using the bacteria Streptomyces mobaraensis.

The main producer of transglutaminase is a Japanese company, Ajinomoto, which sells

it under the name Activa. (This is the same company that originally formed to

manufacture and sell MSG.)

Chemistry. Transglutaminase is an enzyme that binds the amino acid glutamine with a variety

of primary amines. Any place where glutamine and a suitable amine are present,

transglutaminase can be used to crosslink the two. Transglutaminase is itself

digestible (it’s a protein) and the enzymatic reaction ceases after a few hours, so

there’s no danger of it “gluing” your insides together (once it has set, that is,

which would happen during cooking anyway). Transglutaminase acts as a catalyst on

glutamine and lysine, causing the atoms composing the two groups to line up so that

they form covalent bonds.

Note:

A covalent bond is one in which two atoms share an electron, resulting in a lower

energy state. Electrons are “lazy” in the sense that they prefer states that take less

energy to maintain.

To visualize the reaction, imagine spreading apart the fingers of your left and right

hands and touching the tips together, left thumb to right thumb, left pinky to right

pinky, etc. Without some amount of coordination, getting the atomic “fingers” to line up

just doesn’t happen. Transglutaminase helps by providing the necessary atomic-level

guidance for the two groups to touch. And once they touch, they can form covalent bonds

and stick. Continuing the finger analogy, it’s a bit like having superglue on your

fingers: once they are lined up and are touched together, they stay together.

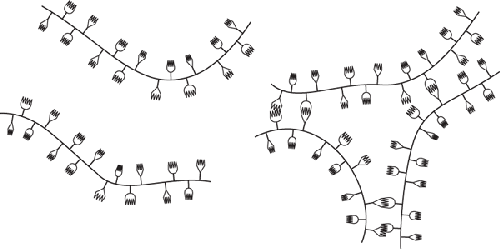

Before interaction, strands of proteins with glutamine and lysine groups

are unattached (left); after interaction, the glutamine and lysine groups are

covalently bonded wherever transglutaminase has a chance to catalyze. Note that

transglutaminase itself does not remain as part of the bond after the

reaction.

While you can pull apart items joined with transglutaminase, the

individual meats themselves may be weaker than the join.

|

Technical notes

|

|---|

|

Concentration

|

~0.5% to 1% of meat weight.

|

|

Notes

|

Cold-set for at least two hours—that is, apply to meat and let rest in

fridge for two hours. Reaction time is correlated with temperature, so it takes

longer to set at colder temperatures.

|

|

Temperature

|

Heat-stable once set.

|