3.5. Vegetables

The geeky way to think about cooking is to consider

the addition of heat to a system. Adding heat isn’t a spontaneous thing: there will

always be a heat gradient, and the difference between the starting and target

temperatures of the food will greatly affect both the cooking time and the steepness of

the gradient.

This is one reason to let a steak rest at room temperature for 30 minutes before

grilling: 30 minutes is short enough that bacterial concerns are not much of an issue,

but long enough to lower the temperature difference between raw and cooked steak by a

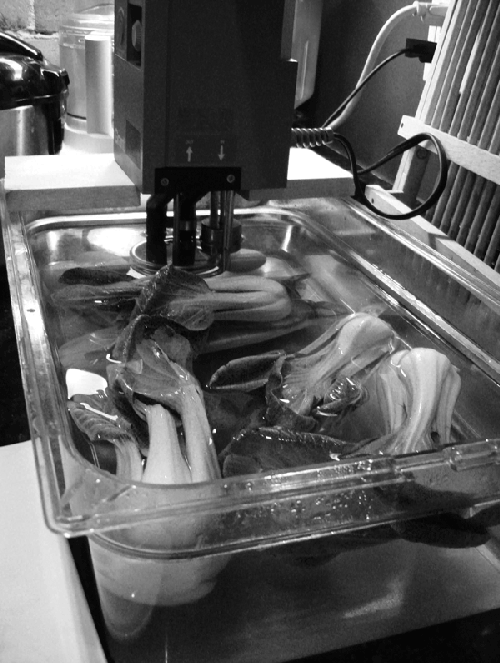

third. You can use a water bath to the same effect for vegetables: reduce the heat delta

by holding them in a moderate-heat water bath (say, 140°F / 60°C) for 15 to 20 minutes,

and then steam or sauté them.

Note:

Yes, you can cook vegetables sous vide, too, but because vegetables don’t begin to

cook until relatively high temperatures—typically above 185°F / 85°C—and even then

take a while, it’s easier to cook them with traditional techniques.

I often cook steak tips at the same time that I preheat bok choy, Swiss chard, or

other hearty greens, using the same water bath for both the steak and the veggies. This

works because the veggies don’t actually cook at the temperature that the meat is

cooking at.

This technique works great for small dinner parties. I bag and seal the steak tips

just before my guests show up, and once they arrive, I drop the bag of steak tips and

some bok choy into a water bath set to 140°F / 60°C. Thirty minutes or so later—after

catching up with my guests, sharing a beer or glass of wine, and noshing on cheese and

bread—I pull the steak tips out and let them rest for a few minutes, during which time I

quarter the bok choy and steam it in a hot frying pan.

Because the bok choy is already warm, it reaches a pleasant cooked texture in two to

three minutes, at which point I transfer it to the dinner plates. Reusing the same

frying pan, I quickly sear the outside of the steak tips, which I then cut and transfer

to the plates. Total time spent while guests wait? Five minutes, tops. Number of dirty

dishes? One, plus plates. And it’s delicious!

3.5.1. Enhancing texture

Ever wonder why some vegetables in canned soups are mushy, textureless blobs, but

others aren’t? Some vegetables—carrots, beets, but not potatoes—exhibit a rather

counterintuitive behavior when precooked at 122°F / 50°C: they become “heat

resistant,” so they don’t break down as much when subsequently cooked at higher

temperatures. Holding a carrot in a water bath at around 120°F / 50°C for 30 minutes

causes enhanced cell-cell adhesion, science lingo for “the cells

stick better to each other,” which means that they’re less likely to collapse and get

mushy when cooked at higher temperatures.

During the precooking stage, calcium ions help form additional “crosslinks”

between the walls of adjoining cells, literally adding more structure to the vegetable

tissue. Since “mushy” textures occur because of ruptured cells, this additional

structure keeps the vegetable tissue firmer by reducing the chance of cellular

separation.

The normal solution to mushy vegetables is to refrain from adding them until close

to the end of the cooking process. This is why some beef stew recipes call for adding

vegetables such as carrots only in the final half-hour of cooking.

For industrial applications (read: canned soups), this isn’t always an option. In

home cooking, you’re unlikely to need this trick, but it’s a fun experiment to do. Try

holding carrots at 140°F / 60°C for half an hour and then simmering them in a sauce

mixed in with a batch of sliced carrots that hasn’t been heat-treated. (You can cut

the heat-treated carrots into slightly different shapes—say, slice the carrot in half

and then half-rounds, versus full-round slices—if you don’t mind your experiment being

obvious.)