2. Sous Vide Hardware

Sous

vide cooking requires very little in the way of hardware: a heater to keep the water bath

at temperature, and a vacuum sealer to package foods so that they can be placed in the

water bath without coming into direct contact with the water. While the commercial tools

can still set you back many hundreds of dollars, a DIY version can easily be made for less

than $100, and resealable plastic bags can be used in lieu of a standard vacuum

system.

2.1. Water heaters

One difficulty of sous vide cooking is maintaining a water bath at a precise

temperature, +/– 2°F / 1°C. The early days of sous vide cooking used laboratory

equipment designed to hold water baths at the precise temperatures needed for

controlling chemical reactions, but as you’d imagine, the lab gear has the drawback of

being expensive. We’re right on the cusp of a wave of new products targeted at the home

chef who wants to cook sous vide, and while the prices might still be out of your reach,

they’ll surely come down until at some point the “three-in-one rice cooker” (steamer and

slow cooker, too!) will become a four-inone rice cooker.

Industrial circulators. These are lab-grade units

that either are designed to be submerged into a container of water (e.g., hotel pans) or

are enclosures with built-in containers. PolyScience is the most common manufacturer

(http://www.cuisinetechnology.com), with new

units costing around $1,000. Grant is also a common maker (http://www.grantsousvide.com). With luck, you can pick up a used

unit at an online auction site for considerably less, but be aware that you’ll have no

idea what chemicals or pathogens a used unit might have been exposed to. If you do go

this route, a three-step wash seems to be the standard cleaning regimen suggested: run

it in a bath of vinegar, then one of bleach, and finally one of rubbing alcohol.

Consumer sous vide products. With the popularity

of sous vide rising, a number of consumer products have recently been released or are in

development that bring the cost of the hardware down to the $400 range, such as the Sous

Vide Supreme. While still on the expensive side, as a piece of consumer kitchen

equipment, it’s not unreasonable, and prices will inevitably fall. Given the versatility

and usefulness of the cooking technique, definitely consider looking at this category of

products.

DIY sous vide. Other commercial products supply

the “sous vide logic” but are BYOHS (bring your own heat source). Appliances like slow

cookers contain the necessary cooking parts already: they hold a reservoir of liquid,

have a heating element, and are designed to run for extended periods of time. You can

repurpose them for sous vide cooking by adding an external controller that switches the

slow cooker on and off to keep it near a target temperature. See the sidebar on making

your own sous vide rig for details.

If you’re the type inclined to fiddle

with electronics, you can build your own sous vide rig by ordering a few parts online

and spending a few hours tinkering. The actual electronics necessary to maintain a water bath at a set temperature are

simple enough: a basic slow cooker, a thermocouple, and a simple thermostat controller

to switch the heat source on and off. First, the slow cooker. The slow cooker will

serve as the brawn, holding the water and providing the heat source. Snag a cheap slow

cooker—you need one that will turn back on after losing power. Look for one that has a

physical knob; the digital ones reset and stay off after power has been cut and then

restored.

Next, the thermocouple. If you have a standard

kitchen probe thermometer (which you really should), the probe—long braided cable,

metal probe—is a thermocouple. For a sous vide rig, you’ll need a type J thermocouple,

which is made of materials that give it good sensitivity in the temperature ranges of

sous vide cooking. This should cost around $15 to $20; search online for “type J

probe” or search for part 3AEZ9 on on http://www.grainger.com. Finally, the temperature controller. Just about

any thermocouple-based temperature switch will work; look for one that runs off 12

volts DC, such as Love Industries’ TCS-4030, which runs about $75. Snag a 12-volt wall

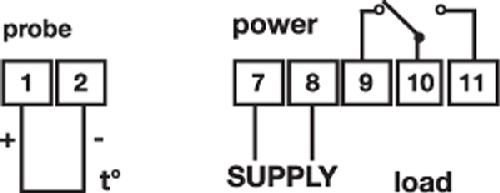

wart (AC/DC power adaptor) while you’re at it. Once you have all the parts on hand, it’s a relatively straightforward procedure

to perform the lobotomy on the slow cooker: hook the thermocouple up to the probe

inputs on the switch and connect the 12-volt power supply to the switch, then snip the

slow cooker’s electrical cord and run one side of it through the switch. Create a

small hole in the lid of the slow cooker and poke the thermocouple through. Make sure

you use enough water in the slow cooker that the thermocouple makes contact with the

water when the lid is on!

|

2.2. Vacuum packers

Regardless of what type of vacuum packer you use, make sure that the plastic bag

you’re using is heat-stable.

Commercial in-chamber vacuum sealers. The

industrial vacuum sealers create a (mostly) air-free chamber (a true vacuum).

Unfortunately, they cost thousands of dollars. Fortunately, you don’t need one. While

there are a number of handy applications for them (mmm, watermelon

steak), sous vide doesn’t require this level of vacuum seal.

Consumer vacuum food sealers. These devices suck

the excess air out of a plastic bag and then seal the bag by means of melting and fusing

the opening of the bag. They don’t create a true vacuum (in the sense that the food

isn’t subjected to a reduction in atmospheric pressure), but they do pull out most of

the excess air. This is perfect for sous vide, because the function and purpose of the

bag is just to allow rapid heat transfer from the water bath to the food via convection

currents. Air in the bag would both slow the rate of heat transfer and also cause the

bag to float in the water, preventing the face-up side of the bag from absorbing

heat.

Resealable plastic storage bags. Sealable

sandwich and storage bags (e.g., Ziploc bags) are not safe for

boiling food. The concern with boiling applications is the

potential for the plastic to leach into the food. The melting point of the type of

plastic used in these bags is only a few degrees higher than the boiling point of water.

BPA (bisphenol A) contamination would also be of concern, especially if you are adding

oils inside the food. Check to make sure the manufacturer of the bags you have does not

use BPA.

Note:

SC Johnson, the manufacturer of Ziploc-branded bags, does not use BPA.

Sous vide cooking, however, does not boil the water. 170°F / 75°C is about the

highest temperature you might use in sous vide applications; 140°F / 60°C is about the

warmest that’s commonly encountered. Is 170°F / 75°C safe? SC Johnson is on record

claiming that, yes, “[Ziploc] bags can be safely heated to 170 degrees Fahrenheit

[76°C].”

Remember, the function of the bag is to allow heat to pass quickly from water to

food via convection, so if you do use a plastic bag, make sure to remove as much air as

possible. You can submerge most of the bag, leaving just the sealing strip at the top

above water, and then seal it. Adding a bit of olive oil or marinade helps, because

it’ll better conform to the shape of the food.

How did you hear about sous vide, and how did you get

involved in it?

I was reading an article in the New York Times by Harold

McGee, and he mentioned sous vide. While I knew quite a bit about cooking, I had never

heard the term before and was intrigued. So I did what any good geek does: I went to

Google and did some research. There was some information but not enough to meet my

curiosity. So I turned to the academic journals and found a wealth of

information.

It took me three or four months to collect and distill the 300 or so journal

articles I found and publish the first draft of my guide online. I also did some

calculations to figure out how long it takes things to cook and how long it takes to

make them safe.

Safety is one of the big topics that comes up with sous

vide and I’d love to talk about that in a moment. But first, what turned out to

matter more than you expected when cooking sous vide?

People always worry about the vacuuming process, but that’s really the least

important part, even though the name sous vide means “under vacuum.” It’s really the

precise temperature control that is important.

Long-term precision is important, because you don’t want slow drifts when you’re

cooking for days to cause your meat to be overcooked. But short-term fluctuations in

temperature really aren’t that important because they will only affect the very outer

portion of the meat. As long as the heat is oscillating less than one or two degrees

Fahrenheit and the mean temperature is constant, you should be fine.

Wow! Cooking meats for days? What sorts of meats actually

need cooking for that length of time?

Well, my favorite is beef chuck roast cooked for 24 hours at 130°F / 54.4°C. It’s

delicious. It transforms one of the least expensive cuts of beef into something that

looks and tastes like prime rib.

It’s all about the conversion of collagen into gelatin. This conversion is pretty

rapid at higher temperature, taking only 6 to 12 hours at 175°F / 80°C to completely

convert everything—well, almost everything. But at lower temperatures like 130–140°F /

54.4–60°C, it can take 24 to 48 hours for the same conversions to occur.

When I look at something like

brisket being cooked at 130°F / 54.4°C for 48 hours, alarm bells go off in my head.

Isn’t there a potential bacterial risk here?

Well, certainly there’s no risk at 130°F / 54.4°C. The pathogen that determines

the lowest cooking temperature is Clostridium perfringens. Its

highest temperature reported in literature is 126.1°F / 52.3°C. So as long as you’re

above that temperature, there won’t be any food pathogens growing.

Now, there is the possibility of spoilage or beneficial microorganisms growing at

these lower-cooking temperatures. That’s one of the reasons that some people will sear

ahead of time or drop the package of vacuum-sealed food in a pot of boiling water for

a couple of minutes to kill off any thermophilic microorganisms that might be in

there, like lactobacilli. But, in terms of safety, there’s no concern

whatsoever.

How about things like salmon, which are cooked at even

lower temperature ranges than 130°F / 54.4°C?

If you would be fine eating the salmon raw, then cooking it for a couple of hours

at a very low temperature, say 113°F / 45°C, isn’t going to be a problem. If you

wouldn’t be comfortable eating it raw, then you probably shouldn’t be cooking it at

anything less than pasteurization temperatures and times.

Most food scientists and food safety experts agree that you should pasteurize

fish. Even though it may not taste the same, or possibly quite as good, at least

you’ll feel a little more safe.

Food safety is about controlling both the actual and the perceived risk. Many

people perceive the risk of fish to be much less than the risk of pork, but in many

ways it’s probably the other way around.

In our modern agro-industrial complex, we don’t really know where things come

from. With this decrease in knowledge of where our food came from, what field, how it

was processed, and how it finally gets to our table, I tend to take the attitude of

“pasteurize everything and hope for the best.” Though it may not be what everyone

wants or likes to hear.

What are the risks and what can somebody in the kitchen do

to partially mitigate those risks?

When you’re trying to deal with food safety, especially when it comes to

pathogens, it is about three things. First, starting with a low initial level of

contamination, which would mean buying, for example, very good and very fresh fish for

which you know the origin. The second is to prevent the increase in the level of

contamination and is frequently accomplished with cold temperatures or acids. The

third is reducing the level of contamination, usually by cooking.

The problem is that if you’re cooking fish sous vide at only 113°F / 45°C, then

you won’t reduce the pathogens to a safe level. So either pasteurize your fish by

cooking it at 140°F / 60°C for about 40–50 minutes or make sure that very few

pathogens grow and that the fish has a very low amount to begin with by buying from a

trusted source.

Can one reduce the level of parasites by

freezing?

Parasites, certainly. Though freezing fish at home will affect the quality of

fish, because consumer freezers just can’t freeze the fish fast enough to prevent

large ice crystals from forming. Now, it’s completely possible that you can buy

already frozen, high-quality fish, or simply find out from your fishmonger whether or

not it has already been frozen for a sufficient amount of time to kill any

parasites.

But freezing won’t kill the different bacterial food pathogens that one might be

concerned with, and there’s always the concern of chemical contamination, especially

with shellfish that are harvested from questionable waters.

How do you know if something will work when you go to sous

vide it?

I never really know, but I like to really scour the research journals for clues to

the underlying processes involved. I first look to see if anyone else has already done

it. With the wealth of scientific knowledge now available to us through the Internet,

it’s very likely that someone has asked and answered a closely related question. Then

I just try and adapt it to the home kitchen.

It always surprises me how often I can take things directly from an academic

journal and apply them in the kitchen.