3.6. Chocolate

Tempering chocolate—the process of selectively melting

and solidifying the various forms of fat crystals in cocoa butter—can be an intimidating

and finicky process. The chocolate must first be melted to above 110°F / 43°C, then

cooled to around 82°F / 28°C, and then heated back up and held between 89°F / 31.5°C and

91°F / 32.5°C. Once tempered, you must play a thermal balancing act: too warm, you lose

the temper, and too cold, it sets.

It’s not exactly correct to describe chocolate as something that “melts,” because

chocolate is a solid sol, a colloid of two different solids: cocoa powder and cocoa

fats. The cocoa powder itself can’t melt, but the cocoa fats that surround it can. Cocoa

butter contains six different forms of fats, and each form melts at a slightly different

temperature.

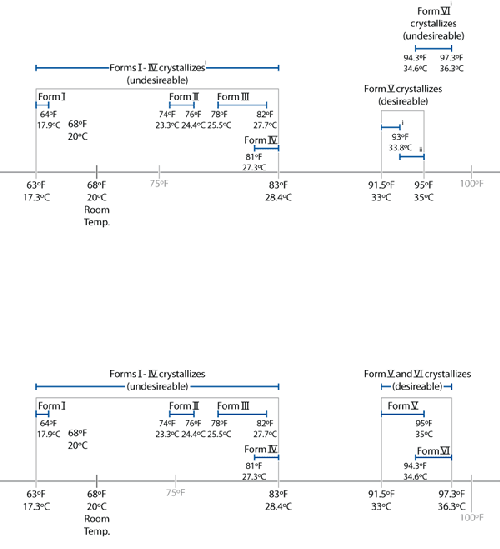

The six forms of cocoa fat are actually six different crystalline structures of the

same type of fat. Once melted, the fat can recrystallize into any of the six forms. It’s

for this reason that tempering works at all—essentially, tempering is all about coercing

the fats to solidify into the desired forms.

Melting points of the six polymorphs of cocoa fat.

Note:

How do scientists tell when something is melting? Two common techniques are used:

differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and x-ray diffraction. In DSC, energy is added

to a closed system at a controlled rate, and the temperature of the system is

monitored. DSC picks up phase changes (e.g., solid to liquid) because phase changes

require energy without a temperature change. X-ray diffraction looks at how x-rays

scatter when passed through a sample: with each phase change, the x-ray pattern

changes.

It’s not a matter of different types

of fats; it’s the structure that the fat takes upon solidifying that determines its

form. Two of these forms (Forms V and VI) link together to create a metastructure that

gives chocolate a pleasing smoothness and firm snap when broken. Chocolate with a high

number of Form V structures is said to be tempered. The other

primary forms (I–IV) lead to a chalky, powdery texture. Form VI occurs in only small

quantities, due to the temperature range at which it crystalizes. Chocolate that has

been exposed to extreme temperature swings will slowly convert to Forms I–IV. Such

chocolate is described as having bloomed—the cocoa particles and

cocoa fats separate, giving the chocolate both a splotchy appearance and a gritty

texture.

To further complicate things, the fats in cocoa butters don’t actually melt at an

exact temperature, and the composition of the fats varies between batches. The ratio of

the different fats determines their exact melting point, and the ratio varies depending

upon the growing conditions of the cocoa plant. The fat in chocolate from beans grown at

lower elevations, for example, has a slightly higher melting point than chocolate from

beans grown at higher, cooler elevations.

Still, the temperature variances are relatively narrow, so the ranges used here

generally work for dark chocolates. Milk chocolates require slightly cooler

temperatures, because the additional ingredients affect the melting points of the

different crystalline forms. When looking at chocolate for tempering, make sure it does

not have other fats or lecithin added, because these ingredients affect the melting

point.

Luckily for chocolate lovers worldwide, chocolate has two quirks that make it so

enjoyable. For one, the undesirable forms of fat all melt below 90°F / 32°C, while the

desirable forms noticeably melt around 94°F / 34.4°C. If you heat the chocolate to a

temperature between these two points, the undesirable forms melt and then solidify into

the desirable form.

The second happy quirk is a matter of simple biology: the temperature of the inside

of your mouth is in the range of 95–98.6°F / 35–37°C, just above the melting point of

tempered chocolate, while the surface temperature of your hand is below this point.

Sure, a certain sugar-coated candy is known to be made to “melt in your mouth, not in

your hands,” but with properly tempered dark chocolate, the sugar coating isn’t

necessary (it is necessary for milk chocolate, though, which melts at a temperature

lower than that of your hand).

Note:

M&Ms were developed in 1940 by Frank C. Mars and his son, Forrest Mars, Sr.

During the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), Forrest saw Spanish soldiers eating

chocolate that had been covered in sugar as a way of “packaging” the chocolate to

prevent it from making a mess.

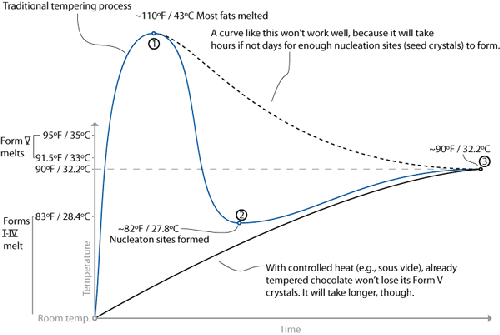

How does all of this relate to sous vide cooking? Traditional tempering works by

melting all forms of fat in the chocolate, cooling it to a low enough temperature to

trigger nucleation formation (i.e., causing some of the fat to crystallize into seed

crystals, including some of the undesirable forms), and then raising it to a temperature

around 90°F / 32.2°C, where the fats crystallize to make Form V crystals.

This three-temperature process requires a watchful eye and, during the second step,

constant stirring to encourage the crystals to form while keeping them small. Water

baths allow for a shortcut in working with chocolate: already tempered chocolate doesn’t

need to be tempered if you don’t get it any hotter than around 91°F

/ 32.8°C. The desirable forms of fat won’t melt, so you’re good to go. To melt already

tempered chocolate, seal it in a vacuum bag and submerge it in a water bath set to 91°F

/ 32.8°C. (You can go a degree or so warmer; experiment!) Once it’s melted—which might

take an hour or so—remove the bag from the water, dry the outside, and snip off one

corner: instant piping bag.

Temperature versus time chart for melting and tempering

chocolate.

If you’re going to be

working with chocolate on a regular basis, the sous vide hack will probably get tiring.

It works, but if you have the dough to spend, search online for chocolate tempering

machines. One vendor, ChocoVision, sells units that combine a heat source, a motorized

stirrer, and a simple logic circuit that tempers and holds melted chocolate suitable for

everything from dipping fruit to coating pastries to filling chocolate molds. Of course,

if you have a slow cooker, thermocouple, and temperature controller...