3. Cooking with Sous Vide

While the general principles of sous vide cooking are the same

regardless of the food in question, the exact temperatures required to correctly cook and

pasteurize it depend upon the specifics of the item at hand. Different meats have

different levels of collagen and fats, and denaturation temperatures for proteins such as

myosin also differ depending upon the environment that the animal came from. Fish myosin,

for example, begins to denature as low as 104°F / 40°C, while mammalian myosin needs to

get up to 122°F / 50°C. (Good thing, too, otherwise hot tubs would be torture for

us.)

Because meats can be grouped into general categories, we’ll cover them in broad

categories. We’ll look at beef and other red meats together, for example, but keep in mind

that variations between different red meats will mean that very slight changes in cooking

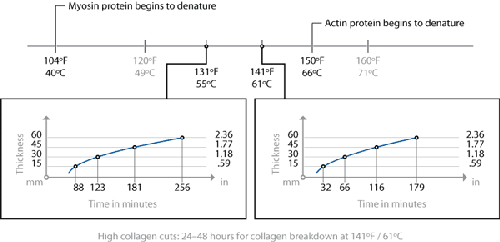

temperature can yield improvements in quality. Data for the graphs in these sections are

from Douglas Baldwin’s “A Practical Guide to Sous Vide Cooking”; see the interview with

him on the previous page for more information.

3.1. Beef and other red meats

There are two types of meats, at least when it comes to cooking: tender cuts and

tough cuts. Tender cuts are low in collagen, so they cook quickly to an enjoyable

texture; tough cuts require long cooking times for the collagen to dissolve. You can use

sous vide for both kinds of meat; just be aware of which type of meat you’re working

with.

Time at temperature chart for beef and other red

meats.

One of the

primary benefits of sous vide is the ability to cook a piece of meat, center-to-edge,

to a uniform level of doneness. Beef steak tips are a great way to demonstrate

this. Place in a vacuum bag: 1–2 pounds (~1 kg) steak tips, cut into individual

serving sizes (7 oz / 200g) 1–2 tablespoons (15–25g) olive oil Salt and pepper, to taste

Shake to coat all sides of the meat with the olive oil, salt, and pepper. Seal the

bag, leaving space between each piece of meat so that the sous vide water bath will

make contact on all sides. Cook in a water bath set to 145°F / 63°C for 45 minutes. Remove bag from water

bath, snip open the top, and transfer the steak tips to a preheated hot pan, ideally

cast iron. Sear each side of the meat for 10 to 15 seconds. For a better sear, don’t

move the meat while cooking each side; instead, drop it on the pan and let it sit

while searing. You can create a quick pan sauce using the liquid generated in the bag during

cooking. Transfer the liquid from the bag to a skillet and reduce it. Try adding a

dash of red wine or port, a small pat of butter, and a thickening agent such as flour

or cornstarch. Notes In sous vide applications, it is generally easier to portion out the

food into individual serving sizes before cooking. This not only helps transfer

heat into the core of the food faster (less distance from center of mass to

edge), but it also makes serving easier, as some foods—especially fish—become

too delicate to work with after cooking. You can still seal all the pieces in

the same bag; just spread them out a bit to allow space between the pieces once

the bag is sealed. I find adding a small amount of olive oil or another liquid helps

displace any small air bubbles that would otherwise exist in a dry-packed bag.

The quantities of oil and spices are not particularly important, but the direct

contact between the spices and food does matter. If you add spices or herbs,

make sure that they are uniformly distributed throughout the bag; otherwise,

they will impart their flavor only to the pieces of meat they are

touching.

|

Some chemical reactions in cooking are a

function of both time and temperature. While myosin and actin proteins denature

essentially instantly at sufficient temperatures, other processes, such as collagen

denaturation and hydrolysis, take noticeable amounts of time. The rate of reaction

increases as temperature goes up, so while collagen begins to break down at around 150°F

/ 65°C, duck legs and stews are often simmered at or above 170°F / 77°C. Even at this

temperature, the collagen still takes a matter of hours to break down.

The drawback to cooking high-collagen meats at this temperature, though, is that

actin also denatures. While the fats in high-collagen cuts of meats can mask this, there

is still a certain dryness to the finished dish. Since collagen begins to break down at

a lower temperature than actin, though, it’s possible to avoid this. The catch is that

the rate of reaction is so slow that the cooking time stretches into days. With sous

vide, though, this isn’t a problem, if you don’t mind the wait.

Seal in a vacuum bag: 1–2 pounds (0.5–1 kilo) high-collagen meat, such as

brisket, chuck roast, or baby-back pork ribs 2+ tablespoons (30g) sauce, such as barbeque sauce,

Worcestershire sauce, or ketchup ½ teaspoon (3g) salt ½ teaspoon (3g) pepper

Cook for 24 to 48 hours at 141°F / 60.5°C. Cut bag open and transfer the meat to a

sheet pan or baking dish and broil to develop browning reactions on outside of meat,

one to two minutes per side. Transfer liquid from bag to a saucepan and reduce to

create a sauce. Try sautéing mushrooms in a pan in a bit of butter until they begin to

brown and then adding the sauce to that pan and reducing until the sauce is a thick,

almost syrupy liquid. Notes If your meat has a side with a layer of fat, score the fat to allow

the marinades to contact the muscle tissue underneath. To score a piece of meat,

drag a knife through the fat layer, creating a set of parallel lines about 1″ /

2 cm apart, then a second set at an angle to the first set to create a diamond

pattern. For additional flavors, add espresso, tea leaves, or hot peppers

into the bag, along with whatever liquid you use. Liquid smoke can give it a

smoky flavor as well. If your sous vide setup does not have a lid, be careful that water

evaporation doesn’t cause your unit to burn out or auto–shut off. One technique

I’ve seen is to cover the surface of the water with ping-pong balls (they

float); aluminum foil stretched over the top works as well.

|