3.3. Chicken and other poultry

One of

the greatest travesties regularly foisted upon the American dinner plate is overcooked

chicken. Properly cooked chicken is succulent, moist, and bursting with flavor—never dry

or mealy. True, the potential of contracting salmonellosis from undercooked chicken is

real; besides, raw chicken is just gross. But I’m not suggesting undercooking

chicken—just cooking it correctly.

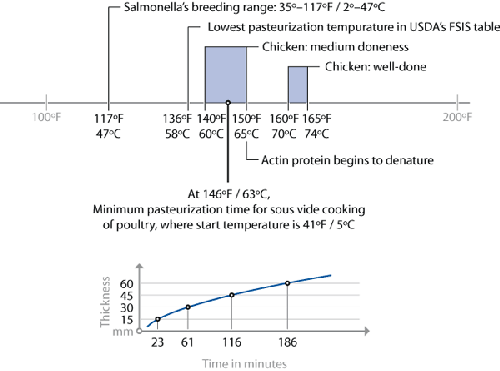

The “problem” with cooking chicken “correctly” is that, from a food safety

perspective, ensuring pasteurization (sufficient reduction of the bacteria that cause,

say, salmonella) requires holding the chicken at a high enough temperature for a

sufficiently long period of time. “Instant” pasteurization can be done at 165°F / 74°C,

but at this temperature the actin proteins will also denature, giving the chicken that

unappealing dry, mealy texture. However, pasteurization can be done at lower

temperatures, given longer hold times. Sous vide is, of course, extremely well suited

for this: so long as you hold the chicken for the minimum pasteurization time required

for the temperature you’re cooking it at, you’re golden. Even if you hold it too long,

as long as it’s below the temperature at which actin denatures, the chicken will remain

moist. Another win for sous vide!

Time at temperature chart for poultry.

3.4. Sous vide chicken breast

As with fish, you don’t need a recipe in the

traditional sense to try out sous vide cooking with chicken. Here are some general

tips:

Chicken has a mild flavor that is well suited to aromatic herbs. Try adding

rosemary, fresh sage leaves, lemon juice and black pepper, or other standard flavors

in the bag. Avoid garlic, however, because it tends to impart an unpleasant flavor

when cooked at low temperatures. When adding spices, remember that the items in the

bag are held tightly against the meat, so herbs will impart flavors primarily in the

regions that they touch. I find that finely chopping the herbs or puréeing them with

a bit of olive oil works well.

As with other sous vide items, allow space between the individual items in the

vacuum bag to ensure more rapid heat transfer, or place individual portions in

separate bags.

“Wait a sec,” you might be thinking, “this ‘sous vide’ thing...how’s it different

from a slow cooker?” I thought you’d never ask!

They’re not actually that different. Both hold a reservoir of liquid at a

high-enough temperature to cook meat but not boil water. Sous vide cooking has two

advantages over traditional slow cooking, though: the ability to dial in a particular

temperature, and to minimize the amount of variance that occurs around that

temperature.

With a slow cooker, your food cooks somewhere in the range of 170–190°F / 77–88°C.

The exact temperature of your food and the extent to which that temperature fluctuates

aren’t so important for most slow-cooked dishes. This is because slow cooking is

almost always done with meats that are high in collagen, these types of meat need

longer cook times in order for the collagen to denature and hydrolyze and transform

into something palatable.

However, this isn’t true for cuts of meat that are low in collagen, such as fish,

chicken breast, and lean cuts of meat. For these low-collagen items, cooking needs to

denature some proteins (e.g., myosin) while holding other proteins native (e.g.,

actin). The difference in temperature at which these two reactions occur is only 10°F

/ 5°C, so precision and accuracy are important. Sous vide wins hands down. It’s not

even close.

Try cooking ducks legs both ways. Seal up two legs and cook them sous vide at

170°F / 77°C. Meanwhile, prepare a second set of legs in a slow cooker. Cook for at

least six hours and then examine the difference.

Sous vide duck legs.

Slow-cooked duck legs.