| Q: |

What sort of sleep problems do children get?

| | A: |

Children can experience the same sort of primary sleep disorders that adults do ,

although the prevalence of disorders is much lower. With the childhood

obesity epidemic in Western countries, however, sleep apnea may become

more common in children than previously. Medical illnesses and mood

disorders that affect the child’s health will also impact on sleep, just

as they do in adults.

|

| Q: |

How can I tell if my child’s sleeplessness is due to a medical disorder?

| | A: |

Most common conditions that disrupt sleep are due to pain, fever,

and discomfort. One of the more common childhood illnesses is otitis

media (an infection of the middle ear), which can cause sleep problems.

The sleep disturbances come in the form of frequent and prolonged

arousals at night and associated daytime sleepiness. A significant

decrease in daytime activity can also occur. Prompt treatment results in

prompt resolution of nocturnal symptoms. Nevertheless, it is important

to maintain sleep hygiene and a regular sleep-wake schedule as much as possible during an illness. A child with a fever requires more sleep.

|

| Q: |

How is sleep affected in children with neurological disorders?

| | A: |

Disturbed sleep is often a feature of children who have problems

with their nervous system or have either been born with or acquired an

impairment of the senses, such as sight, hearing, and movement.

Sleeplessness and night-time awakening are frequent occurrences.

Children with blindness and deafness may also experience significant

disorders of the sleep-wake cycle.

|

| Q: |

How are sleep disorders treated in children who have significant handicaps?

| | A: |

Sleep disorders in such children can be difficult to treat so it

is best to seek professional help. You and your child may benefit from

seeing a sleep specialist who may undertake investigations to assess how

disturbed your child’s sleep really is and whether there are any other

concurrent disorders. It is also important to establish whether another

medical disorder needs to be excluded before a diagnosis is made.

Whatever the sleep disorder turns out to be, it can be treated by a

variety of methods, as in adults.

|

| Q: |

Is attention deficit hyperactivity disorder a sleep problem?

| | A: |

Generally, parents of hyperactive children consider them to have

more sleep disturbances than children who are not hyperactive. Children

with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder tend to have more

difficulty getting to bed and falling asleep, and are more restless

sleepers, but there is some controversy over the issue of whether they

have more disrupted sleep patterns than other children. Many hyperactive

children also have frequent awakenings at night and increased

restlessness. The occurrence of bed-wetting and sweating at night are more common compared to children without hyperactivity.

|

| Q: |

What are the characteristics of children with hyperactivity?

| | A: |

Children should be diagnosed as being hyperactive or having ADHD

(attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) only by a specialist. Among

the characteristics are a tendency to be fidgety and easily distracted,

to disturb other children at school, to have difficulty concentrating

and completing tasks, and to have rapid mood swings. Most children are

restless and can become easily frustrated and rapidly destructive.

|

| Q: |

Can children with sleep apnea become hyperactive?

| | A: |

Yes. Children with significant sleep apnea will often behave in a

very similar manner to children with ADHD. However, children with sleep

apnea snore at night and there may be periods during the day when they

are more sleepy than usual.

|

| Q: |

How should a child with hyperactivity be investigated?

| | A: |

As stated above, the diagnosis of ADHD should only be made by a

specialist because it has many implications for the child and for the

child’s treatment. If sleep apnea is suspected, it must be investigated.

There are many ways of managing hyperactivity including stimulants,

counseling, and behavior modification (which can also be applicable to

parents/caregivers). Once treatment is started, sleep problems tend to

improve.

|

| Q: |

What are some of the more common childhood sleep disorders?

| | A: |

Children can suffer from primary sleep disorders just like adults

do. The more common disorders that need to be considered in infants and

toddlers have already been described. Other disorders include problems

with limit-setting (often a parental problem), night-time fears,

sleep-walking and sleep-talking, night terrors, bed-wetting, snoring and sleep apnea, and disorders of circadian rhythms, especially in adolescence.

|

| Q: |

My child is frightened of going to bed– what can I do?

| | A: |

Night-time fears are very common in childhood. Children have

active imaginations and may often experience vivid nightmares. Many

fears occur as part of normal development, including fear of loss and

separation from a parent/caregiver, sibling rivalry, and fear of death.

These fears may be expressed through increased aggression, mood swings

and moaning, and fear of sleeping alone or being left by the

parent/caregiver at night.

|

| Q: |

How do I deal with fear in my child?

| | A: |

It depends on how long-standing and severe the problem is. If it

has lasted a while and been difficult to manage, then you should consult

a child psychologist. However, if you are aware of the fear developing

and it has been present for a short while, your child may only need some

understanding and firm support. Continue with bedtime rituals, but stay

with your child a bit longer until he or she has settled, then

withdraw. Changing the bedroom environment may make your child feel more

secure.

|

| Q: |

Why is it such a struggle to get my child into bed every night?

| | A: |

You are probably giving in to your child’s protests and have

stopped being persistent and consistent with a bedtime routine and sleep

hygiene measures. Rather than weathering the tantrums that will

eventually subside anyway, you are reinforcing this protesting behavior

and rewarding your child by giving in. Make sure you establish a bedtime

routine and that other factors, such as the child sharing a bedroom

with a brother or sister with different sleep requirements, is not

undermining your efforts. You must stick to the regimen without fail,

and be positive but firm. Consistency and persistence are important.

Avoid becoming angry or threatening punishment because this leads to

increased tension. You must decide who is going to win the bedtime

struggle–you or your child?

|

| Q: |

What are night terrors?

| | A: |

In children, night terrors (pavor nocturnus) occur with the child

suddenly awakening from slow wave sleep with a piercing scream or cry,

accompanied by intense fear. The child might have a racing heart and

feel sweaty. The attacks usually resolve by themselves. Night terrors

occur regularly in 3 of 100 children, and occasionally in up to 15 in

100. They usually end during adolescence.

|

| Q: |

I find night terrors in my child very distressing–can they cause any harm?

| | A: |

Even though the sight of your child gripped by a night terror

will upset you, try not to be distressed. The most important thing to

remember is that, during a night terror, your child will not come to any

harm and will not remember the event. Night terrors do not have any

negative long-term consequences for your child’s growth or development,

nor are they a sign of any mood disorder or psychological problem.

|

| Q: |

Is there anything I can do when my child has night terrors?

| | A: |

Make sure that your child’s sleeping environment is safe and that

he or she cannot come to any major harm due to a fall from the bed. For

example, it’s not a good idea to let your child sleep on the top bunk

if he or she sleep-walks or gets up during a night terror. Ensure a

pleasant bedtime routine and consistent sleep-wake times for your child.

If the problems are severe, occur very frequently, or don’t seem to

disappear as the child gets older, it is best to seek professional

advice. Occasionally, medication will be useful and counseling may be

necessary. You do not have to sit up all night by your child’s bed.

Gently guiding your child back to bed without awakening him or her is

all that is necessary.

|

| Q: |

What is sleep-walking?

| | A: |

Sleep-walking consists of a series of complex behaviors that

occur in slow wave sleep. Sleep-walking may stop spontaneously or the

sleep-walker may return to bed. Falls and injuries may occur if walking

leads to dangerous situations, such as out of a door and into the street

or through a window. Sleep-walking occurs regularly in 1 to 3 in 100

children, and occasionally in up to 29 in 100 children. It will usually

disappear after adolescence.

|

| Q: |

My child has started sleep-walking–is there anything I can do about it?

| | A: |

It is important to ensure that the environment is safe and that

your child cannot walk through a window, plate glass door, or out of the

house. You may need to install child-proof locks on doors or an alarm

system on doors and windows. Don’t let a sleep-walking child sleep on a

top bunk. Try and ensure a regular sleep-wake schedule. In a child with

frequent sleep-walking or who sleep-walks more often when distressed,

medication and counseling may be appropriate. Guide your child gently

back to bed; if you awaken the child, no harm will come to him or her.

|

| Q: |

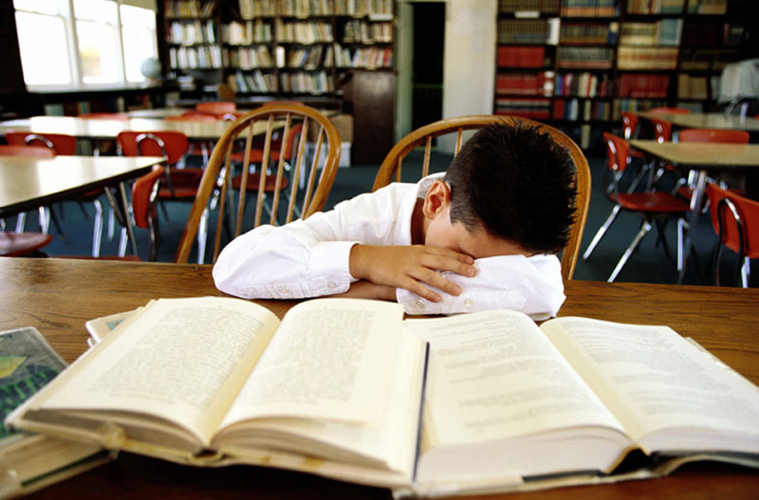

My child is abnormally sleepy during the day–what could be causing this?

| | A: |

Reasons for being sleepy during the day include: not enough sleep

at night due to frequent awakenings or an irregular sleep-wake regimen,

an illness which is disrupting sleep and causing daytime sleepiness,

circadian rhythm disorders, narcolepsy and other forms of daytime

sleepiness (very rare), and sleep apnea.

|

| Q: |

How common is sleep apnea in childhood?

| | A: |

About 3 to 12 in 100 children snore regularly and, of these,

about 1 to 3 in 100 have sleep apnea. Children with certain

developmental disorders (such as Down syndrome) have an increased risk

of sleep apnea. As obesity increases among children in our society,

sleep apnea may become more common.

|

| Q: |

What are the consequences of sleep apnea in childhood?

| | A: |

Just as in adults, the consequences can be serious. These include

adverse effects on the heart, blood vessels, and intellectual

development, the latter leading to learning disabilities, behavioral

problems (such as hyperactivity), and aggressive behavior. The

repetitive dips in oxygen levels overnight in children with sleep apnea

can have drastic and far-reaching effects on the developing brain.

|

| Q: |

How can I tell if my child has sleep apnea?

| | A: |

Loud snoring on a nightly basis is almost universally present in

children with sleep apnea. The snoring is accompanied by labored

breathing, breathing pauses, and choking noises. Sometimes, children

with sleep apnea will wet the bed, experience sweating at night, and

wake up with a dry mouth in the morning. Children are not often sleepy

during the day, unlike adults, so attention must be paid to other

indicators such as poor school performance, aggressive behavior,

hyperactivity and morning headaches. If sleep apnea is very severe, a

child can have failure to thrive. As in adults, the best way to diagnose

sleep apnea is by doing an overnight sleep study. If you suspect that

your child has sleep apnea, you must discuss this with your doctor and

seek referral to a specialist for assessment.

|

| Q: |

How is sleep apnea treated in children?

| | A: |

The most common causes of sleep apnea in normal children are

related to structural problems with the face or jaw, or to large tonsils

and adenoids. Tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy are the first-line

treatment for sleep apnea in children and are relatively simple surgical

procedures to perform. However, they must be performed only after a

specialist has fully investigated the child’s sleep disordered breathing

at night. Surgery to the jaw (if it is very small) or orthodontic

treatment may be necessary in a small number of children with sleep

apnea. CPAP treatment is also used . Children who are obese must lose weight.

|

| Q: |

My child snores–is this OK?

| | A: |

Recent evidence suggests that children who snore have increased

respiratory effort with the snoring. This may have adverse effects on

behavior and intellectual functioning. If you are concerned about your

child’s snoring, especially if it is loud, disruptive, and habitual,

consult your doctor.

|

How Can I Tell if my Child has a Sleep Problem?

Always consider the

possibility of a sleep problem if your child is sleepy during the day

(this is abnormal for children who have a healthy balanced lifestyle),

has started to show a decline in schoolwork or interest in activities,

if his or her mood or activity levels have changed, or his or her

behavior is becoming increasingly difficult or unpredictable. A simple

way to remember the different causes of sleep problems is with the

mnemonic “B.E.A.R.S.”

If you have answered

yes to any of these questions (or if your child’s sleep-wake routine is

irregular) and you are concerned about your child’s sleep or daytime

function, please seek medical advice.

B stands for bedtime problemsDoes your child have difficulty getting to sleep? Does your child resist going to bed? Does your child take a long time to fall asleep?

E stands for excessive daytime sleepinessIs your child abnormally sleepy during the day? Does your child have great difficulty getting up in the morning? Does it take your child a while to get going in the mornings? Does your child fall asleep for no reason during the day? Does your child nap during the day (apart from developmentally appropriate naps)? -

A stands for awakenings at nightDoes your child get up frequently during the night? Does your child stay up for long periods during the night? Does your child suffer from nightmares or night-time fears? Does your child sleepwalk regularly or wake up with night terrors? -

R stands for regularity and duration of sleepHow long does your child need to sleep? What is your child’s sleep pattern like? Can your child follow a strict bedtime routine and get up at the same time every day? -

S stands for snoringDoes your child snore during sleep? Does your child have breathing pauses during sleep? Does your child get easily tired during the day or have behavioral problems, or has his or her school performance dropped off?

Bed-wetting

Bed-wetting during

sleep is also called sleep-related enuresis. Enuresis is very common and

at any one time millions of children suffer from it. Bed-wetting can be

described as either primary or secondary. In primary enuresis, the

child has never learned to control his/her bladder. In secondary

enuresis, the child has at some stage been dry all night for at least 3

months.

Generally, enuresis

should not be considered a significant problem under the age of 5 years

if the child is developing and progressing normally. Approximately 3 in

10 four-year-olds have nocturnal enuresis, but only 1 in 10

six-year-olds, 3 in 100 12-year-olds, and 1 in 100 15-year-olds. Under

the age of 11 years, boys are twice as likely to have problems as girls.

There appears to be a familial predisposition: if a child has problems

with nocturnal enuresis, there is a high chance that one or both parents

had problems in childhood with enuresis as well.

What causes bed-wetting?

The precise

causes of sleep-related enuresis are not known. In primary enuresis, it

is thought to be a problem with immaturity of the bladder and the

systems in the body that relate to its control and the regulation of

urine production. Primary enuresis will generally end with time and with

the child’s ongoing development. Secondary sleep-related enuresis is

often associated with either the development of illness or with

psychological factors.

A urinary tract infection

is one of the more common causes of secondary enuresis. A urinary tract

infection should be considered a possibility if there is wetting during

the day as well as at night, abdominal pain, and burning or stinging

when urinating. Other illnesses that can cause secondary enuresis

include diabetes mellitus, kidney failure, and neurological problems

relating to bladder control. Emotional problems commonly resulting in

sleep-related enuresis include stress, family break-up and bereavement.

If you are worried about your child’s enuresis, then you must seek

medical advice.

What can I do about my child’s bed-wetting?

If your child has had a

period of being dry and suddenly starts wetting the bed at night, you

must seek medical advice. The bedwetting may be the result of

psychological stress or the development of an illness.

If your child wets the bed even though she or he is old enough to stay dry, then the following tips might be useful:

Make sure your child goes to the toilet before getting into bed. Restrict fluids an hour before going to bed–no final drinks before or while actually in bed. Wake your child during the night when he/she normally wets the bed and take your child to the toilet. Wearing diapers may be helpful. A

bell-and-pad device is sometimes used. An alarm goes off whenever the

pajamas or bed become wet. This is supposed to condition your child to

wake up and feel the discomfort of being wet. Medication

can be used but only if it is prescribed by your doctor. Medications

commonly prescribed for enuresis include imipramine and desmopressin. Don’t

punish your child–he or she can’t help it. Be sensitive and don’t talk

about the child’s bed-wetting in front of others. Be patient with your

child.

Prescribed medications for children with sleep disorders

Generally, most problems

with sleep in childhood can be effectively addressed using behavioral

techniques such as implementing a bedtime routine and ensuring that a

regular sleep-wake schedule is consistently adhered to. This means that

parents have to take responsibility and show some discipline themselves.

However, depending on the disorder and its severity, medications can

sometimes be prescribed. Some of the medications that might be

prescribed in the treatment of childhood sleep disorders are listed in

the table.

Table | Sleep problem | Medication | Drug class |

|---|

| Sedation | Diphenhydramine | Antihistamine | | Enuresis; depression | Imipramine | Tricyclic antidepressant | | Enuresis | Desmopressin | Hormone (ADH) analog | | Parasomnias; seizures | Clonazepam | Benzodiazepine | | Sedation | Lorazepam | Benzodiazepine | | Sedation; phase advance | Melatonin | Hormone | | Sedation | Zaleplon | Nonbenzodiazepine | | Sedation | Zolpidem | Nonbenzodiazepine | | Narcolepsy | Dexamphetamine | Stimulant | | Narcolepsy; ADHD | Methylphenidate | Stimulant |

|