Comments about your “ironing-board chest”,

“thunder thighs” or *insert body insult here* can cause lasting damage to your

self-image and confidence. Learn to reclaim them.

Find me a woman who doesn’t keep a secret

mental catalogue – detailed and well thumbed – of the words that have been used

to describe her body.

From the euphemistic “curvy”, “lanky” or

“big-boned” – to the ugly flatness of the F-word itself (that is, “fat”), each

has its own vivid context. Few, to our minds, are neutral observations

unrelated to our sense of self-worth. These archives date back to childhood,

but even the earliest entries seem to gather little dust.

We refer back to them constantly, sometimes

compulsively. They shape the way we think about ourselves and can determine how

we treat our bodies even decades later…

Words will ever hurt me

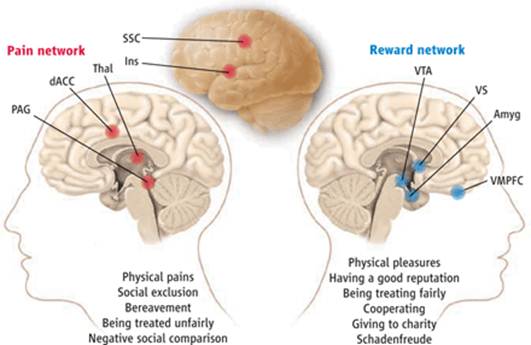

This

network is implicated in physical and social pain processes

In a recent online poll, 72 percent of our

readers admitted to having been hurt by a negative comment about their weight.

Which goes some way to prove that the playground chant about “sticks and

stones” couldn’t be further from the truth.

In fact, studies show that unkind words can

have a much more traumatic and longer-lasting impact than broken bones. In

2008, researchers from the universities of Purdue (US) and New South Wales

(Australia) found that while the memory of physical pain tends to fade with

time, the brain stores and relives “social pain” – such as the pain caused by a

catty or careless comment about your appearance – with enduring clarity.

But why this nasty trick of regurgitating

statements we’d do better to forget? It’s not entirely clear, but the study’s

authors have a hunch. They reported in the journal Psychological Science that

the cerebral cortex (the part of our brains responsible for processing

language) has evolved to make us better members of a group. It’s why we play by

society’s rules (usually, anyway) and why we feel shame when we break them.

But the evolution of this type of grey

matter is probably also why we feel social pain so intensely and so long after

the fact. Call it an unlucky Darwinian quirk.

Write on the body

Words

effect us much more than we realise and cause more pain

Yet not all social pain is the same kind of

sore. I was mortified when my Class One teacher whacked my palm with a rule for

taking too long to complete my sums. That left a dull ache, although it’s still

not in the same category as the boyfriend who exclaimed, “What’s that?!”,

pointing to a dimple of cellulite on my right thigh.

Somehow, comments about our bodies cut

deeper. Possibly they sting so sharply because – as a society – we’re far more

forgiving of a girl who’s not much good at maths than we are of a girl whose

thighs aren’t “perfectly” smooth.

It shouldn’t be this way, of course. But

such is the message we’re fed in words, and their subtexts, from a very early

age. Models, not mathematicians, are held up for public praise.

British psychoanalyst Susie Orbach changed

the way we thought about female bodies in 1978 with her first book Fat is a

Feminist Issue (Arrow).

She argues that we’ve come to value the

body beautiful above all things. In 2009, she made this compelling point in her

book Bodies (Picador): “We used to use our bodies to make things. Now, we make

our bodies instead – they are the product.”

Yet

not all social pain is the same kind of sore

In other words, our abilities, skills and

even character too often – if only sub-consciously – seem to matter less than

how we look. This warped value system frequently confuses attractiveness with

goodness, worthiness and success. In its lexicon, “fat” describes far more than

a bit of excess “adipose tissue” (the medical term). It’s also a synonym for

“stupid”, “lazy”, “poor” and “undesirable”.

Tracy Tylka, an associate professor of

psychology at Ohio State University (US), found that the single most powerful

influence on our body image is not – wait for it – the number we read on the

scale, but rather the opinion of others. Or, perhaps more accurately, our

perception of the opinion of others, which is not always quite the same thing…

“If somebody makes a negative comment, ask

yourself if it’s malicious, or if there’s truth in it” – Rakhi Beekrum,

phychologist