The safari – the Swahili word for “long

journey” – was born in Kenya, the former British colony where barons and

plutocrats, maharajas and royalty once paraded across the plains to play out an

expensive, outlawed fantasy. One blistering summer in this land before time,

Paolo R. Reyes was given a rara opportunity to experience Africa in its age of

innocene

“Kristine Hermosa. You know her? She very

beautiful.” The immigration officer at Nairobi’s Jomo Jenyatta International

Airport inquired – qith a mischievous smile – about the semi-retired Philippine

actress as he stamped my passport with a 90-day tourist visa.

The

safari – the Swahili word for “long journey” – was born in Kenya

I didn’t have time to tell him that I had

interviewed Hermosa for the Inquirer in the past, or that her once-stellar

career had been sidelined by marriage and motherhood. So I flashed him a

similar smile, cracked a corny joke, and took my first step into Kenya: the

land of Out of Arfica safaris, world-class Olympic athletes, Barack

Obama’s forefathers, and, as I soon discovered, defunct Filipino soap operas.

After claiming my luggage at the carousel,

I was met at the arricals hall by Rajab, a representative of my tour operator.

Asia to Africa Safaris, who was to escort my party to the nearby Wilson

airstrip, where a tiny, twinprop De Havilland Otter bound for the wilds of Meru

awaited us.

Before I could even reciprocate Rajab’s

warm “jambo” (Swahili for “hello”), he began interrogating me on what I was

beginning to realize was a local obsession: the dramatic cliffhangers, twisted

storylines, and tantalizing stars of Pangako Sa ‘Yo, Sana’y Wala Nang Wakas,

and Kay Tagal Kang Hinintay.

Nairobi

– the capital city of third-world Kenya

These ABS-CBN telenovelas, all dubbed or

subtitled in the vernacular, have taken the East African nation by storm in

recent years, thus giving these expired Pinoy soaps a second life in the

unlikeliest of places.

Perhaps not so unlikely, I thought, as the

air-conditioned van crawled its way to Wilson, inch by inch, through the

winding, honking crush of traffic that Nairobi – the capital city of

third-world Kenya – has become notorious for.

The two airports are only 12 kilometers

apart, so what should have been a 20-minute drive took us nearly an hour. But

it was a good opportunity to get a glimpse of the capital’s working belly, far

removed from the fancy suburb of Karen (named after Out of Africa author Karen

Blixen), where the country’s 1-percent are ensconced post-colonial estates not

far from the Danish writer’s former coffee plantation.

High up in the air, however, Kenya

transforms into a different kind of creature – primal, prehistoric, and capable

of inspiring wonder. As we hovered over game reserves where the grass seemed to

roll on forever, the jangled din of the city dissolved into the gentle lull of

the jungle.

“They’ve pumped so much money into

this place, it’s incredible,” I overheard my seatmate, the Vanity Fair and New

York Times photographer Guillaume Bonn, tell the plussized American woman behind

him as the De Havilland plane made its descent on the $1.25 million Meru

National Park.

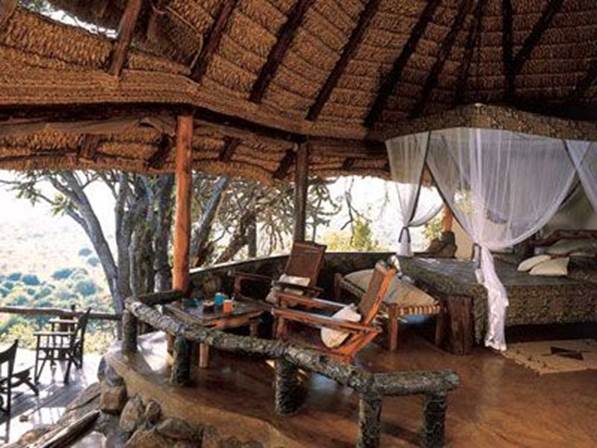

Elsa’s

Kopje - the first stop of my week-long safari, is a cluster of open-faced

casitas built into the jagged folds of Meru’s Mughwango Hill

Bonn, a French photojournalist born in

Madagascar, has covered the dark continent for over a decade, from the murder

of conservationist Joan Root in Lake Naivasha to the Lord’s Resistance Army

(LRA) of fugitive warlord Joseph Kony in North Uganda. (His photographs of the

latter ran alongside a controversial Vanity Fair piece, “childhood’s

End,” written by the late Christopher Hitchens.)

Today, on commission for Condé Nast

Traveler, he was en route to Lewa, the 60,000-acre wildlife consevancy

where Prince William famously proposed marriage to Kate Middleton in a rustic

log cabin overlooking Mount Kenya.

The whirr of the plane’s propellers

prevented me from probing him further. But I gathered from the gruff, inposing

tone of his voice that this was no fluff piece on a five-star ecolodge or

glamping site – which was where I, like most of the khaki-clad holidaymakers on

board the flight, was headed.

Elsa’s Kopje, the first stop of my

week-long safari, is a cluster of open-faced casitas built into the

jagged folds of Meru’s Mughwango Hill, a pyramid of granite marooned in a sea

of thorny thickets. It’s a luxury lodge with a killer view and storied past.

Fifty years ago, before the park was nearly

destroyed by bandit gangs that swept down from Somalia in search of ivory and

rhino horn, this was the lair of Elsa the Lioness. The eccentric Adamsons,

George and Joy, hand-raised the orphaned cub like their own child and

reluctantly released her into the wilderness – a heart-wrenching tale of two

conservationists that was immortalized in the 1966 movie Born Free.

Looking out from the balcony of my cotage,

dramatically perched on a drooping lip of the kopje (small moutain), I

understood how John Barry had been inspired to compose the epic film’s

Oscar-winning score. Down below, on a corn-colored earth specked green with

doum palms and baobab trees, Rothschild giraffes and Grevy’s zebras were

cantering away in the twilight, as a thirsty herd of elephants dipped their

trunks into the Rojewero river, one of 13 tributaries that bisect the park like

tea-brown ribbons.

Looking

out from the balcony of my cotage, dramatically perched on a drooping lip of

the kopje (small moutain), I understood how John Barry had been inspired to

compose the epic film’s Oscar-winning score

Francis Epong, a native of the Turkana

tribe, served as our guide at Elsa’s Kopje. Tall, weather-beaten, and hardened

by the harsh climate, he was a throwback to the days of the white hunter and

the memsahib (colonial women) – always ready to cater to our group’s

varied whims, whether it was a champagne breakfast in the bush or a request to

rifle through the forest to search for the elusive leopard.

As with most safaris, our days at Elsa’s

began before the crack of dawn, while the stars were still visible and as the

mists rolled back slowly in the sunrise; a magical hour for bush walks and game

drives, when the landscape and all it’s the living creatures seemed to be in

the process of being created.

The day ended, more often than not, with a

sundowner at dusk, in an open-sided Land Rover well-stocked with wine and

liquor. Upon returning to the lodge, the walinzi (night watchmen) would

lead us to the clubhouse at the windy crag of Mughwango Hill, where a

multi-course Italian dinner would be served under an intermittent shower of

meteors.

The

day ended, more often than not, with a sundowner at dusk, in an open-sided Land

Rover well-stocked with wine and liquor.

Canopied under this cloudless sky the color

of midnight, you will sometimes hear – if you’re lucky – the guttural moan of a

wandering lioness, as if the ghost of George and Joy Adamson’s Elsa still

haunted the savannah into which she was released.

After Two Spine-Crunching hours on highways

that have seen better days, and a quick stopover at Isiolo, a sleepy backwater

town where the men chewed on miraa (a herbal amphetamine), I finally

arrived at the east gate of Shaba, a 59,000-acre reserve where the reality show

Surivor: Africa was shot 10 years ago.

As my driver left the Land Rover to pay the

entrance fee at the ranger’s station, I played a game with a few persistent

locals, mostly children, who were peddling all manner of trinkets, nacklaces,

and carved animal figurines outside my window.

“I will buy something if you can guess

which country I’m from,” I declared, as the crowd, their faces pressed against

the glass, gathered around the jeep like a friendly mob. They couldn’t, even

with my clues. When I pacified their growing frustration by shouting

“Philippines!” they erupted in laughter, still puzzled perhaps by the odd

provenence of this passing stranger.

The

Boran-style tent suite of glamping resort Joy’s Camp

In Shaba, the equatorial sun doesn’t so

much shine as strike. But its Martian landscape, unchanged for thousnands of

years, makes up for the blistering heat. In this parched corner of Kenya’s

northern frontier, not far from Ethiopia, the Pleistocene Era anjoys a kind of

eternal life: the volcanic mountain ranges of Bodich and Ol Kanjo swoop up

theatrically from the savannah, where rust-colored boulders the size of buses

are scattered on the red earth like forgotten dinosaur eggs.

For this second leg of the safari, I was

lodged at Joy’s Camp, a lowkey “glamping” resort. In the late 1970s, Joy

Adamson called this remote corner of the reserve her home. It was then a

ramshackle of tables and chairs, paint brushes and paper where she wrote her

final book, The Queen of Shaba, and was mysteriously murdered in the

summer of 1980. A concrete cairn, just behind the camp, marks the spot where

she was slain.

If you’re looking for isolation – a real

selling point for seasoned safari-goers – Joy’s Camp is the place to find it.

Managed by Willem Dolleman and Francien van de Vijver, an eco-conscious Dutch

couple in their late twenties, the camp os made of up 10 tented suites, all

designed around an exotic Moorish theme inspired by the local Boran tribe.

The main dining tent, a Mediterranean-style

oasis with a springwater swimming pool, overlooks a veritable Garden of Eden –

a lush green plain with a large natural spring where lions, reticulated

giraffes, and elephants vie for watering rights with buffalo, Beisa oryx, and

zebras.

To truly appreciate the volcanic terrain of

Shaba, you must confront nature on your own feet. Instead of a game drive on my

final day, I opted for a treacherous trek through the Ewaso Nyiro River’s

unforgiving gorge: a daredevil’s playground of predators, abandoned poachers’

caves, and poisonous plants that can render a man blind.

The

Ewaso Nyiro River

Together with my guide, John Ebukutt, and

an armed game scout in military fatigue (“Whatever you do, don’t run,” he

warned me), we trudged cautiously through the steep ochre wall of the ravine,

the river’s chocolate-brown waters surging 40 feet below us, until we clawed

our way down to a sandy beach, where we could make out the spoor of freshwater

Nile crocodiles and the footprints of baboons.

At the flat crown of the canyon, we came

face-to-face with the prehistoric panorama of Shaba: a sweeping, grandstand

view of Creation, the kind one imagines God might have had on the third day.

Even in the blinding haze of high noon, it was possible to imagine what it must

have looked like in the beginning.

The Story Goes that when John Galliano, the

disgraced British fashion designer, first set foot on Elephant Pepper – a

traditional campsite in the beating heart of the bush – his jaw dropped upon

catching sight of his “suite.”

Canopied under a grove of pepper trees

where Vervet monkeys played and found, and garrisoned by a row of Maasai

tribesmen clad in Shuka blankets, was a bare-bones canvas tent with a backyard

unlike any other: the game-rich grasslands of the Maasai Mara, Kenya’s most

famous wildlife reserve.

The witnesses I spoke to couldn’t confirm

whether Galliano raised his sculpted eyebrows in delight or disbelief. But for

most first-item guests at Elephant Pepper Camp, the third and final leg of my

Kenyan safari, it’s usually a mix of both.

With limited mobile phone access, no

generators (twelve solar panels power the entire site, when needed), no

permanent structures (mindful of their eco-footprint, everything is completely

mobile), and an unfenced location inhabited by all creatures wild and free,

Elephant Pepper Camp offers what most five-star African lodges cannot: an

opportunity to experience Kenya in its age of innocence.

Elephant

Pepper Camp

The Mara, once the world’s most popular

playground for hunters and poachers, was where this European pastime of

game-viewing began in the 19th century. In those days, when

well-heeled Westerners with a sense of adventure went on “safari” (the Swahili

word for “journey”), it mean long, treacherous nights on horse-drawn caravans

with a huge contingent of staff and crew ready to pitch a tent and prepare a

campfire come nightfall.

When I arrived during the waning days of

Kenya’s blistering summer, under billowing clouds pregnant with rain, I

realized just how easy it was for writers like Heming way or Huxley to wax

romantic about those halcyon days of the hunt.

Gone, of course, were the crackling sounds

of rifles being fired in the air and the constant drumming of hoofbeats in the

red dirt. As I sat under a ceiling of stars, enjoying my cold glass of Tusker

beer over the campfire, there was only the deafening silence of the night,

interrupted only by a falcon’s contact call in the distance or the deep-throated

roar of a lion.

On

a clearing close to the Leopard Gorge, my guide Stanley Kipkoske called my

attention to a cheetah rustling like a ravenous predator through the grass, her

gaze directed at a helpless prey

The old-fashioned charm of this 20-year-old

mobile camp is its accommodations. Linked together by hurricane lamps and

marked footpaths in the forest, each of the eight canvas tents consist of a

queen-sized bed, an en-suite bathroom (with a wash basin, bucket shower, and

eco-friendly flush toilet), and a private veranda with a hammock perfect for

noontime naps between game drives.

Game drives are the highlight of any safari

in the Mara, a savannah so flat, leveled, and free of obstruction that it

offers camera- and binocular-friendly views of the big cats, wildebeests,

zebras, giraffes, gazelles, and spotted hyenas on parade.

I can still recall the inimitable thrill I

felt when I witnessed my first hill. On a clearing close to the Leopard Gorge,

my guide Stanley Kipkoske called my attention to a cheetah rustling like a

ravenous predator through the grass, her gaze directed at a helpless prey: a

baby Thomson’s gazelle that had strayed away from its pack.

A panicked barking, like alarm bells,

erupted from the herd, a futile attempt to warn the wayward fawn of an

impending attack. My telephoto lens closely followed the action from stalk, to

chase, to kill. In the blink of an eye, it was all over. The predator, her

mouth firmly locked on the bleeding neck of its prey, grew increasingly

paranoid as a flock of vultures began circling overhead in a ritualistic dance

of death.

“The law of the jungle,” Stanley said as I

sat motionless at the edge of my seat.

In the wild, primitive corner of Arica, a

land before time where man stills seems beholden to the beasts of a bygone

world, nature – and not much else – puts on the greatest show on earth.