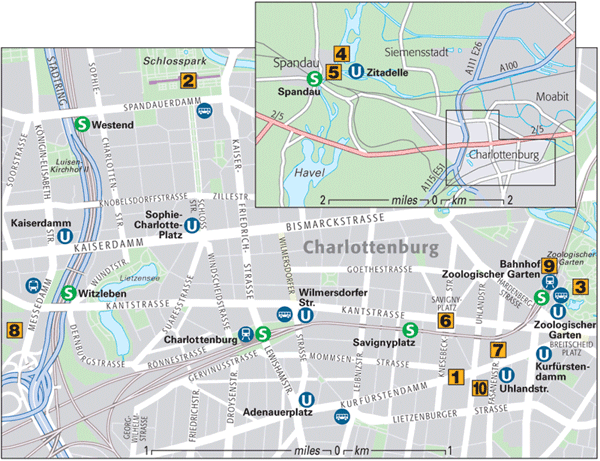

Sophisticated Charlottenburg is a haute bourgeoisie

enclave and was the only district of Berlin that did not rub shoulders

with the Wall. The historical streets off Ku’damm feature small cafés,

restaurants, art galleries and boutiques, based in stout residential

houses from the beginning of the 20th century. These streets and

Charlottenburg’s proud town hall remind us that this district was once

the richest town in Prussia, which was only incorporated into the city

of Berlin in 1920. Spandau, on the other hand, is rural in comparison, a

part of Berlin with a special feel. Spandau’s Late Medieval old town

and the citadel make this district on the other side of the Spree and

Havel seem like a small independent town.

|

West Berliners

consider the Spandauers to be rather different sorts of people,

provincial and rough, and not “real” Berliners at all. But the

Spandauers can reassure themselves that Spandau is 60 years older than

Berlin, and proudly point to their independent history. The mutual

mistrust is not just a consequence of Spandau’s geographical location,

isolated from the remainder of the city by the Havel and Spree Rivers.

It is also due to the recent incorporation of Spandau in 1920. Today,

still, Spandauers say they are going “to Berlin”, even though the centre

of the city is only a few stops away on the U-Bahn.

|

|

The magnificent

Charlottenburger Rathaus (town hall) on Otto-Suhr-Allee is a reminder of

the time when this district of 200,000 people was an independent town.

Charlottenburg, named after the eponymous palace, arose in 1705 from the

medieval settlement of Lietzow. Towards the end of the 19th century,

Charlottenburg – then Prussia’s wealthiest town – enjoyed a meteoric

rise following the construction of the Westend colony of villas and of

Kurfürstendamm. Thanks to its numerous theatres, the opera and the

Technical University, the district developed into Berlin’s west end

during the 1920s.

|

Top 10 SightsKurfürstendamm The famous Berlin boulevard, the pride of Charlottenburg, is today a lively and fashionabale avenue .

Schloss Charlottenburg The Baroque and English-style gardens of this Hohenzollern summer residence are ideal for a stroll . Zoologischer Garten Overlooked by the Great Berlin Wheel, this is Germany’s oldest and most important zoological garden .

Zitadelle Spandau The

only surviving fortress in Berlin, the citadel, at the confluence of

the Havel and Spree Rivers, is strategically well placed. The

star-shaped moated fortress, built in 1560 by Francesco Chiaramella da

Gandino, was modelled on similar buildings in Italy. Its four powerful

corner bastions, named Brandenburg, König (king), Königin (queen) and

Kronprinz (crown prince) are especially remarkable. A fortress stood on

the same site as early as the 12th century, of which the Juliusturm

survives – a keep that served as a prison in the 19th century. At the

time, Berliners used to say, “off to the Julio”, when they sent

criminals to prison. Later the imperial war treasures were kept here –

the reparations paid by France to the German Empire after its defeat in

the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1. The Bastion Königin houses a museum

of municipal history. Am Juliusturm 10am–5pm daily 030 354 944 200 Admission charge

Zitadelle Spandau

Spandau

Old Town When walking

around Spandau Old Town, it is easy to forget that you are still in

Berlin. Narrow alleyways and nooks and crannies around Nikolaikirche are

lined by Late Medieval houses, a sign that Spandau was founded in 1197

and is thus older than Berlin itself. Berlin’s oldest house, the Gothic

House, dating back to the early 16th century, stands here, in Breite

Straße 32.

Prussian Eagle in Spandau

Inside Nikolaikirche, Spandau Old Town

Savignyplatz One

of Berlin’s most attractive squares is right in the heart of

Charlottenburg. Savignyplatz, named after a 19th-century German legal

scholar, is the focal point of Charlottenburg’s reputation as a district

for artists and intellectuals and as a trendy residential area for

dining out and entertainment. The square has two green spaces, either

side of Kantstraße. It was built in the 1920s as part of an effort to

create parks in the centre of town. Small paths, benches and pergolas

make it a pleasant place for a rest. Dotted all around Savignyplatz are

restaurants, street cafés and shops, especially in Grolman-, Knesebeck-,

and Carmerstraße, all three of which cross the square. Many a reveller

has lost his way here after a night’s celebrating, which is why the area

is jokingly known as the “Savignydreieck” (the Savigny Triangle). North

of Savignyplatz it is worth exploring some of the most attractive

streets in Charlottenburg – Knesebeck-, Schlüter- and Goethestraße. This

is still a thriving Charlottenburg community; the small shops, numerous

bookstores, cafés and specialist retailers are always busy, especially

on Saturdays. South of the square, the redtiled S-Bahn arches also lure

visitors with their shops, cafés and bars; most of all the

Savignypassage near Bleibtreustraße and the small passageway between

Grolman- and Uhlandstraße on the opposite side of the square. Fasanenstraße This

elegant street is the most attractive and trendiest street off Ku’damm.

Designer shops, galleries and restaurants are tucked away here, a

shoppers’ paradise for all those who regard Kurfürstendamm as a mere

retail strip catering for the masses. The junction of Fasanenstraße and

Ku’damm is one of the liveliest spots in Berlin. One of the best known

places is the “Bristol Berlin Kempinski” at the northern end of Fasanenstraße. The Lübbecke & Co bank

opposite cleverly combines a historic building with a new structure.

Next to it are the Jüdisches Gemeindehaus (Jewish Community House) and a little farther along, at the junction with Kantstraße, is the Kant-Dreieck. Berliner Börse (stock exchange), based in the ultra-modern Ludwig-Erhard-Haus,

is just above, at the corner of Hardenbergstraße. The southern end of

the street is dominated by residential villas, some of which may seem a

little pompous, as well as the Literaturhaus, Villa Grisebach, one of

the oldest art auction houses in Berlin, and the Käthe-Kollwitz-Museum.

There are also some very expensive fashion stores here, as well as a

few cosy restaurants. At its southern end, the street leads to

picturesque Fasanenplatz, where many artists lived before 1933.

The Jewish House, in Fasanenstraße

Kempinski Hotel Bristol Berlin, Fasanenstraße

Shops in Fasanenstraße

Funkturm and Messegelände The

150-m (492-ft) high Funkturm (TV tower), reminiscent of the Eiffel

Tower in Paris, is one of the landmarks of Berlin that can be seen from

afar. Built in 1924 to plans by Heinrich Straumer, it served as an

aerial and as an air-traffic control tower. The viewing platform at 125 m

(410 ft) provides magnificent views, while the restaurant, situated at

55 m (180 ft), overlooks the oldest part of the complex, the exhibition

centre and the surrounding pavillions. The giant building in the east is

the Hall of Honour built to designs by Richard Ermisch in 1936, in the

colossal Fascist architectural style. On

the opposite side rises the shiny silver ICC, the International

Congress Centrum, built in 1975–9 by Ralf Schüler and Ursulina

Schüler-Witte. It is still considered one of the most advanced

conference centres in the world, with 80 rooms for more than 5,000

visitors. Berlin’s vast exhibition grounds are among the largest in the

world, covering an area of 160,000 sq m (40 acres). These play host to,

among others, Grüne Woche (green week, an agricultural fair),

Internationale Tourismusbörse (international tourism fair) and

Internationale Funkausstellung (international TV fair).

Ehrenhalle in the Messegelände

The Berliner Funkturm

Newton Sammlung Helmut

Newton (1931–2004), the world famous photographer, has finally returned

to his home city. This museum presents his complete works and centres

on two shows called “Sex and Landscapes” and “Us and Them”, which show

his early fashion and nude photography as well as photos of the famous,

rich and beautiful since 1947. Käthe-Kollwitz-Museum The

museum is dedicated to the work of the Berlin artist Käthe Kollwitz

(1897–1945), who documented the misery of workers’ lives in 1920s Berlin

in numerous prints, graphics and sketches. After losing a son and a

grandson in World War I, she concentrated on the themes of war and

motherhood. The museum holds some 200 of her works, including several

self-portraits. Fasanenstr. 24 11am–6pm daily 030 882 52 10 Admission charge

|