Sightseeing is for the day time

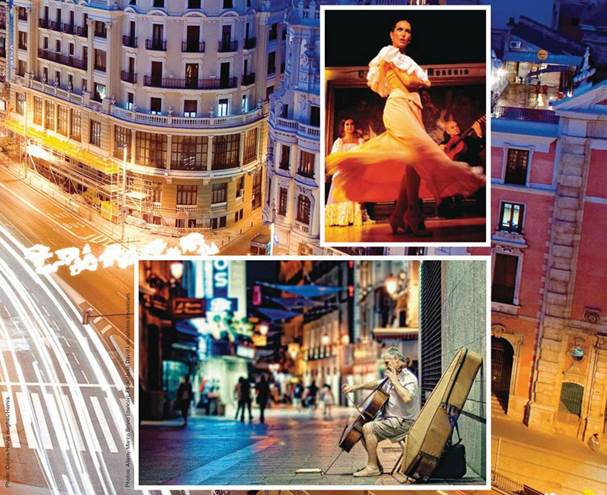

In Madrid, the rule of thumb is: the later

the hour, the louder the nightlife. This is a city that doesn't seem to sleep.

Taxi drivers told me there are more people on the streets at 3 a.m. than at 3

p.m., and it seemed to me to be true. Walking back to my hotel on the Gran Via

at 4 a.m. Sunday morning was like walking down Toronto's Yonge Street at

Christmas. It was packed. People were shoulder to shoulder on a very wide

sidewalk.

Musical

Midnights in Marid

Madrid is an insomniac's dream destination.

No matter how late it is, you're never alone. I left restaurants at 11 p.m. and

saw families just sitting down for what would be a four- or five-course meal. I

walked the streets at midnight and saw whole families out, from children in

strollers to grandmothers. Suddenly, I didn't feel so much the night owl.

I wondered how people managed it. I know,

you're thinking "siesta." I sure took them, especially after the

two-hour massive lunches I gobbled down, but many Madrilenos

(Madrid residents) don't take siestas. Madrid is a modern society, doing

business globally, and that can't be put on hold while staff take a nap. People

in the towns bordering the city and the owners of smaller, independent shops

are more likely to close from 2 to 4, but most of the city remains open.

My nocturnal wandering let me discover a

vibrant city awash in music. In the pedestrian zones leading to Plaza Puerta

del Sol, where Madrilenos gather to celebrate the New Year, I heard jazz

musicians, a classical combo teasing superb melodies out of violins and cellos,

and a solo musician playing the Chinese guitar; there were rockers and

folksingers, and even a nine-member South American mariachi band. Farther on, I

listened to a man coaxing serene sounds out of rows of water-filled

glasses. These were the appetizers for nights full of music.

A Magical Evening

On my first night in the city, I wandered

to the Plaza Mayor for something to eat. The Plaza Mayor is the heart of Madrid, the

square where kings have been proclaimed, insurrections launched, and bullfights

held—and where those charmers from the Inquisition carried out public

executions. It's a massive open square set in a quadrangle surrounded by

government offices and apartments. On the lower level is a colonnaded walkway

lined with cafes and restaurants known as "the terraces." Most of the

clientele for these places are tourists. As I walked around the terraces,

reading the menus, I recalled a tour guide, Isabel Viedma, telling me,

"Local people eat in the alleys that lead into it [the Plaza] because the

food is good and cheap. We can't afford to pay what visitors pay."

The

Plaza Mayor

So I headed through the south gate in

search of someplace local. This proved to be one of those delicious

serendipitous treats you hope happens when travelling. I spotted two women

leaving a window table in a red-fronted tavern, the Tres Cuatro Ocho (Three

Four Eight). I dashed in, hoping to grab their seat, but was intercepted by a

young waiter who led me into the back. At first this annoyed me because I

wanted to people-watch, but, after we passed the kitchen and washrooms, I

realized the treat he had in store. In a small archway between two rooms

holding eight tables sat a generously proportioned accordion player. He was

laughing, smiling, waving his head in tune to the music being twisted out of

the box strapped to his chest.

As I wrote in my notebook, people at the

next table asked me something in Spanish. I shrugged and apologized, "English

only." That's when Graham asked if I was a writer. Graham is a retired

software engineer from Scotland who divides his time between a friend's

apartment in Madrid and his own seaside villa. He told me the accordion

player's name was Efrain and that he was a 73-year-old retired

telecommunications technician from Argentina and a newlywed. On this evening,

Efrain's companion wasn't his bride, but a rotating cast of characters who

sang, played guitar, danced, clapped, and generally made it a magical evening.

Efrain played his accordion with both

vigour and a jaunty élan. Sometimes he practically made it cry as he contort

edit around the plaintiveness of a traditional love song. Whether or not you

speak the language, there's a recognizable quality to unrequited and lost love.

During the evening, he was joined by a diverse collection of musical friends.

One of the bar owners sang a flamenco song. A ball-capped man pulled out his

guitar and sang several folk songs, including an Austrian thigh-and-heel-slapping

Schuhplatter folk-dance piece for some German blondes in the corner. Next,

Miguel, a 57-year-old economist—who, with the others at his table, is a regular

on Thursday nights—stood up and sang a series of ballads. Graham then sang, in

Spanish, about a man who goes out with his friends and has a little too much

fun.

Next up was Isabel Pardo, who Graham says

sings professionally. After breezing through "My Way" in Spanish, she

glided from anthem-like calls to action to ballads, boisterous folk songs, and

love songs. Isabel slipped between the men seated around the room, enticing and

teasing them, then in the next moment showed her theatrical ability as she

almost dropped through the floorn in waves of regret, rage, and sorrow over

her" bad decisions."

The music had passion and mischievousness,

and a sometimes lecturing tone, followed by a plaintive baring of the soul, as

if making a confession or pleading undying love. There was no inhibition, no

self-consciousness here. It was simply a great evening in an intimate setting.

After a lengthy series of toasts, gales of

laughter, and more wine, I staggered out into the passing parade of diners at a

respectable 1:30 a.m.

The next evening, again near the Plaza

Mayor, I saw people clustered in the door way of a small tavern. Whenever the

door opened, music splashed into the street. I followed my ears and found 14

men in medieval garb. They wore black coats cinched at the waist with red slits

in the puffy sleeves, white blousey shirts, floppy black hats, knickers, and stockings.

Some had capes. Immediately thought of Zorro and wouldn't have been surprised

if a sword fight had broken out.

These were "La Tuna." Tunas have

been around for centuries here, music groups traditionally made up of

university students. These guys were engineers from a university in Valencia,

and they were great fun. They had everything you could want in tavern music:

energy, humour, and volume. At times, they pounded their mandolins, guitars,

and tambourines with such vigour I thought they would break. And then, as if in

some sort of demented barbershop harmony, they would bounce along in unison

with the music.

I hadn't thought of Spain as having

drinking songs, but this seemed to be what they sang. They made joyful sounds

of epic length. Then, shortly after 1 a.m., they paraded out of the tavern and

into the night, their music echoing in the narrow side streets.