4.2. High-heat ovens and pizza

A serious—some might even say OCD—discussion of pizza is clearly a must-have for a

cookbook for geeks. I’ve tried to restrain myself from dwelling too much on pizza,

but it covers so many variables

in cooking: flavor combinations, Maillard reactions, gluten, fermentation, temperature.

If you want to make a crispy thin-crust pizza, a high-heat oven is critical. It

takes a sufficiently hot environment to set the outer portions of the pizza dough

quickly enough to create the characteristic crispiness and flavors. How hot is hot? The

coldest oven I’ve found acceptable for flat-crust pizza was a gas-powered brick oven at

550°F / 290°C, where the pizza was dropped onto the brick floor of the oven.

The better flat-crust pizza I’ve had is cooked either in wood-fired brick ovens or

on a grill over wood, at 750°F / 400°C, with parts of the oven pushing 900°F / 480°C.

For comparison, my local normal “thick-crust” pizza place runs its oven at 450°F / 230°C

in the winter, 350°F / 175°C in the summer. (The oven can’t be run any hotter in summer

without the kitchen becoming unbearable.)

By trying various temperatures, I’ve found 600°F / 315°C to be the lower limit for

getting a crispy, flavorful crust. At 700°F / 370°C, the crust becomes noticeably

better. And at 950°F / 510°C? It takes 45 seconds to cook a pizza. But how can you get

these temperatures? Most of us don’t have ovens that normally reach 950°F / 510°C, let

alone 700°F / 370°C, and few of us have brick ovens, either. What’s a

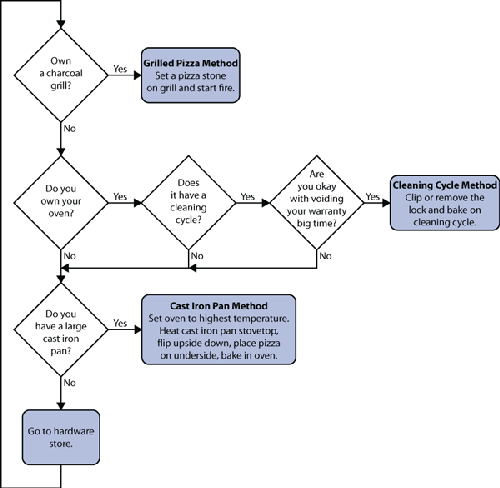

thin-crust-pizza-loving geek to do? If only there were a flow chart for this...

Decision tree for how to cook a pizza.

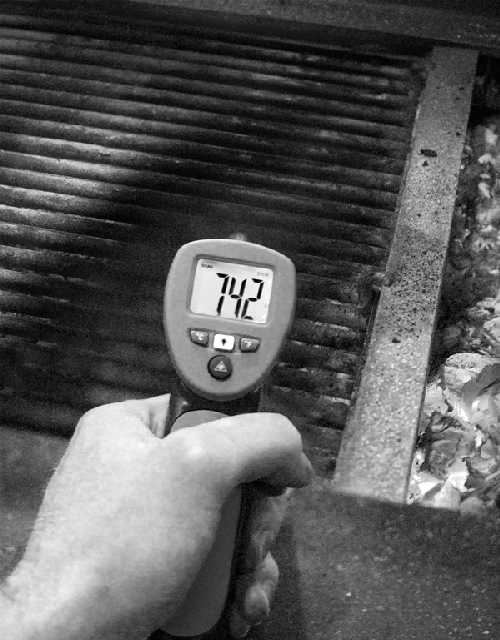

Charcoal or wood grill method. This is by far the easiest

method. Grills fueled by charcoal or wood get hot, easily up into the 800°F / 425°C

temperature range. (Propane grills tend to run cooler, even though propane itself

technically burns hotter.)

Place a pizza stone on top of the grill and light the fire. Once the grill is good

and hot, use a pizza peel (a piece of cardboard works just as well) to transfer the

pizza with toppings onto the grill. Depending upon the size of your grill and the size

of your pizza, you might be able to cook the pizza directly on top of the grill, sans

stone—give both a try!

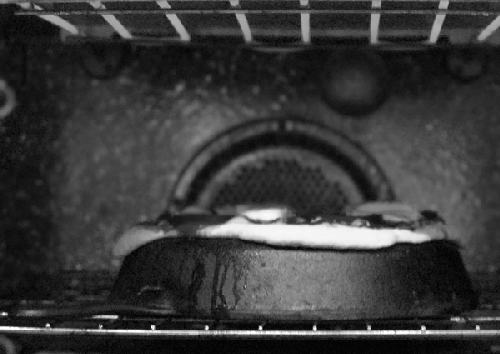

Superhot cast iron pan method. What if getting

a grill isn’t an option for you, as is the case for many apartment dwellers? There are

still a few ways left to get up to sufficiently hot temperatures. While most consumer

ovens reach only 550°F / 290°C, both the oven’s broiler and the stovetop can reach

higher temperatures. Leave an empty cast iron pan on a burner at full throttle and

it’ll reach 650°F / 340°C in 5 or 10 minutes. And the infrared radiation from a

broiler is even hotter.

Preheat oven to 550°F / 290°C, or as hot as it goes.

Superheated cast iron under broiler.

Heat up cast iron pan on stovetop at maximum heat for at least five

minutes.

Place cast iron pan upside down in the oven under a broiler set to high and

par-bake the pizza dough until it just begins to brown, about one to two

minutes.

Transfer dough to cutting board and add sauce and toppings. Transfer back to cast

iron pan and bake until toppings are melted and browned as desired.

If you don’t have a broiler, you can try a doubled-up cast iron pan

approach:

Doubled-up cast iron.

Heat up two cast iron pans on maximum heat.

Par-bake the dough, flip it onto a cutting board, add toppings, and return it to

the hot cast iron pan.

Cover the first cast iron pan with the second one, preferably using a larger pan

so that it doesn’t touch the pizza toppings.

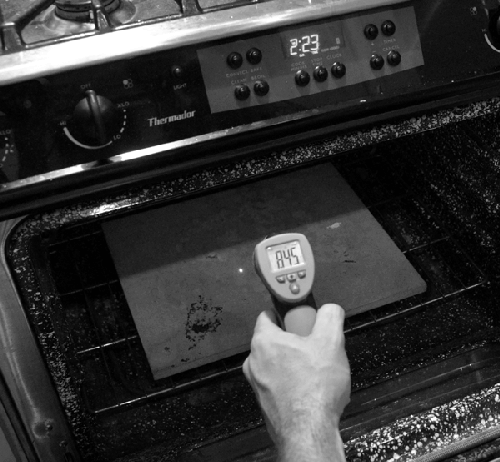

Cleaning cycle method

(a.k.a. “oven overclocking”). As we’ve discussed, one of the key

variables for good thin-crust pizza is an extremely hot oven. Consumer ovens just

don’t get hot enough; 550°F / 290°C is still a good 150–200°F / 80–110°C away from

where the “real” thin-crust pizzas are cooked. If only there were a way to hack an

oven to get it that hot! It turns out that there is, but it’s dangerous, voids your

warranty, and, given that the alternative ways of getting this kind of heat are far,

far easier, is really not worth doing. Still, for the sake of my readers, I tried this

method, conceived by Jeff Varasano.

Ovens get a lot hotter—a lot, lot hotter—when they run in the cleaning cycle. The

problem is that consumer ovens mechanically lock the door, preventing you from

slipping a pizza in and out at those temperatures, and leaving a pizza in for the

entire cleaning cycle will result in a most unpleasant burnt taste, to say the

least.

Cut or remove the lock, however, and ta-da! You’ve got a superheated oven. After a

bit more fiddling and testing, I had an oven that I measured at over 1,000°F / 540°C.

The first pizza we tried took a blistering 45 seconds to cook,

with the bottom of the crust perfectly crisped and the toppings bubbling and

melted.

However, the middle of the pizza—the top portion of the dough and the bottom

portions of the sauce—never had a chance to cook, so the 1,000°F / 540°C pizza wasn’t

quite right (too hot). Another attempt at around 600°F / 315°C resulted in the

opposite outcome: the pizza was good, but it didn’t capture the magic of the crispy

thin crust and toasty-brown toppings (too cold). Around 750–800°F / 400–425°C,

however, we started getting pizzas that were darn good (just right).

Ovens aren’t designed to have their doors opened when running in the cleaning

cycle. Honestly, I don’t recommend this approach. I broke the glass in my oven door

and had to “upgrade” it, although it is cool to have bragging rights to an oven

sporting a piece of PyroCeram, the same stuff the military used for missile nose cones

in the 1950s.

There’s also the issue of how hot the surrounding countertop and cabinetry can

get. Commercial stoves are designed for these sorts of temperatures and as a result

require a large air gap between the appliance and any combustible materials. Given

that an upside-down cast iron pan under a broiler or a wood-fired grill turn out

delicious flat-crust pizzas, I’m afraid I have to recommend that you skip the oven

overclocking, even if it is fun.