What goes on behind those two-way swinging doors leading to

the commercial kitchen? More and more restaurants are sharing with the public what they’re

doing, even going so far as to blog their thoughts and recipes for all the world to see.

Why? Well, for one, it serves as great publicity for the restaurants. And secondly, so much

of what’s done in the high-end modernist restaurants requires so much work that it’s

probably cheaper for a home chef to go and eat at the restaurant than it would be to try

undertaking one of their recipes anytime soon.Even if you’re not going to attempt a full 26-course dinner, you can learn a lot by

seeing how the pros approach food and the lengths to which they go to in their quest for a

truly fantastic and delightful meal.

Since the techniques in this section are not, in and of themselves, going to put dinner

on the table, you might wonder how to work them into your cooking. Think of this section

like knife skills for modernist cuisine: a few pointers for what’s happening behind those

swinging doors.

In this section, we’ll take a look at a few techniques that are common in commercial

restaurants and examine ways that they can be useful to the home chef. This isn’t by any

means a complete list. Rather, this should be enough to get you started thinking outside the

box .

Many aspects of “playing with your food” are

beyond the reach of most commercial restaurants, either because they’re not worth the

time or require a geek to do it. For a few high-end restaurants, spending the time involved in making custom

molds allows them to create innovative and unusual experiences. Working with

fabricators, they’ll create custom silicone molds ranging in shapes of everything from

vegetables to eggs, using them to mold asparagus puree set with gelling agents or for

signature desserts.

Then there’s the geek side of things. If you happen to have access to a CNC

(computer numeric control) printer, such as MakerBot’s Cupcake, try printing your own

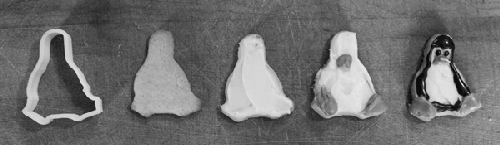

molds and cookie cutters. Here’s an example, using none other than that famous penguin,

Tux. (Tux is the Linux kernel’s official mascot.) You’ll need a cookie cutter, sugar

cookie dough, and frosting. Create the cookie cutter. This is the hardest part

(second hardest, if you’re the type to eat all the cookie dough before getting to the

end). Bake the cookies. Using the cookie cutter (shown on

the left in the photo below), create your Tux cookies and bake. Allow the cookies to cool

before frosting.

Frost. Until MakerBot comes out with a Frostruder

that supports multiple colors, you’ll have to do this by hand. Prepare a batch of frosting and divide it into three bowls, putting most of the

frosting in the first bowl. Add yellow food coloring to the second bowl; you’ll use this

for Tux’s yellow feet and beak. Add red and blue food coloring to the final bowl; when

mixed together, this will make an almost-black frosting. To frost, take a first pass using the white frosting, covering the entire cookie in a

single full layer of white frosting. Using a dinner knife, take a second pass, lightly

smearing the yellow frosting for his beak and feet. For the third pass, transfer the black

frosting to a plastic sandwich bag, snipping off the corner to make a piping bag, and

carefully dot the two eyes and black edge.

|

1. Filtration

Filtering is a common

technique for separating solids from liquids in a slurry. Filtering is usually done to

remove the solids—for example, to create a clear broth free of particulate matter or a

juice free of pulp. Other times, the solid matter, such as browned butter solids, is the

desired item.

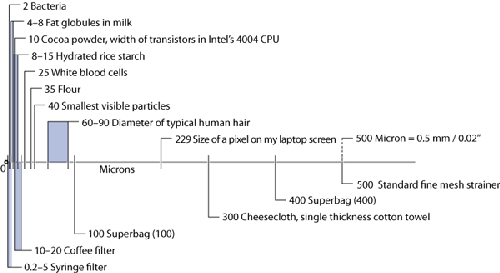

Sizes of common items (top portion) and common filters (bottom

portion).

Besides filtration, which we’ll talk about here, additives can be used to separate out

some types of solids. Some manufacturers use isinglass, a collagen derived from fish

bladders, in beer and wine making. The isinglass binds with yeast and causes it to

precipitate out. (Sorry, vegetarian beer lovers.) And consommé is traditionally clarified

using egg whites, which, like isinglass, bind to small particulates and then coagulate

into a large mass that’s easily removed. Mechanical filtration, in contrast, has the

advantage of being fast and easy.

Reasons for filtering in the kitchen can range from aesthetic (including traditional

broths like consommé) to practical (needing particulate-free liquid to work with in cream

whippers —the particulate would potentially clog the

system).

Which type of filter to use depends on the size of the solids. A

chinois—a conical strainer—is fine for straining out spices and

solids from a broth and is the standard go-to item for filtration. To mechanically mash

foods and give them a finer texture, you can push them through a perforated sheet of

steel. Traditional European soups, such as vichyssoise (potato and leek), pass through

these to ensure a smoother mouth-feel.

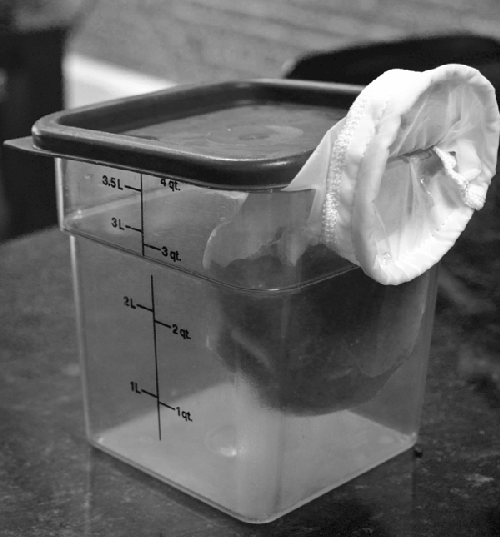

A standard modern technique for making clarified liquids such as

consommés is to freeze the liquid and drip-thaw it through a filter, such as a

Superbag.

High-end chefs use finer

filtration to achieve other effects. Straining out the solids in tomato juice to get a

clear, transparent tomato water requires a much finer filter. You can also use

hydrocolloids: create a gel with gelatin (e.g., stocks) or agar (e.g., Dave Arnold’s lime

juice in The Easier, Cheaper Version of “The $10,000 Gin and Tonic”), and pass the gel

through a filter. The gel will hold on to most of the solids, while the filter will hold

on to the gel.

International Cooking Concepts sells a filter bag called a “Superbag” that’s

dishwasher safe, reusable, and highly durable.

The McMaster-Carr product uses a stiffer material and doesn’t drain as quickly as the

Superbag, however. With this size of filtration, you can quickly create flavored liquids

such as nut milks (purée presoaked almonds, drop in filtration bag, squeeze liquid out) or

fruit juices (purée cantaloupe, drop in filtration bag, squeeze liquid out). Try other

things, such as asparagus and olives.These finer filters can also be used for drip filtration, where the solids are rested

in the filter bag and the liquids are given time to percolate out slowly. Purée tomatoes,

drop them in a fine (~100 micron) filter sleeve, clamp in a storage container, and let

drip overnight in the fridge to create semiclear tomato water.