1.1. Stock, broth, and consommé

Stock, broth, consommé—what’s the difference? Stock and

broth are both liquids made by simmering vegetable and/or animal

matter. Traditionally, stocks are made with bones, which have collagen. Most of this

collagen breaks down and converts to gelatin, which gives the stock a lubricious

mouth-feel and, at sufficient concentrations, causes the stock to turn into a gel when

cooled. The cans of “stock” that you find in the grocery store are really broth—they

don’t have the same level of gelatin that a proper stock should have.

Note:

If the canned “stock” carried in grocery stores had gelatin, it would be gelled

like Jell-O.

Stocks

are generally more of an ingredient—not highly seasoned, usually added to a soup or

dish. Broth is a finished product, and strictly speaking broths should be made without

bones; they contain no gelatin and so are comparatively much thinner than stocks. From a

practical perspective, in home cooking you can treat them as the same thing in most

cases. Just don’t try to make a dish such as aspic that relies on gelatin using

broth.

Both stock and broth contain fats and solid particulate matter from the vegetable

and animal products they’re made with, giving them a cloudy appearance. A

consommé is a clarified version of either stock or broth, from

which the particulates and some of the fats have been filtered out. The traditional

method for clarification involves creating an egg-white “raft” that is gently stirred

while the broth is simmered. It’s time-consuming, and while you should try it sometime,

it’s not likely to be an everyday cooking technique. An easy modern method involves

using the gelatin present in a true stock to trap the particulate matter. Freeze the

stock, and as it thaws, the gelatin will hold on to the particulate matter; thaw it in a

filter that’s fine enough to hold onto the gelatin, and the resulting liquid that passes

through the filter will be consommé.

Okay, this isn’t really filtering in the true sense of the word, but you

can separate a liquid from any compounds dissolved in it by

boiling off the liquid. Think sea salt: saltwater is allowed to evaporate, leaving

behind just the salt. A rotary evaporator (rotovap) is nothing more than a fancy

(and unfortunately very expensive) tool for replicating what happens in a salt flat,

but it’s designed to enable better control and to allow capturing of both parts (i.e.,

the salt and the water after separating). It separates a solvent

from a liquid or solid by gently boiling it away under a precise vacuum and

temperature and then condensing the vapor in a flask, a process known as

distilling. It’s like boiling water on the stove and collecting

the steam that condenses on the lid, but with far more precision. Distilling under a vacuum lowers the boiling point of the solvent (usually water

or ethanol), meaning that any compounds that are heat-unstable remain undisturbed.

With a rotovap, alcohol or water can be boiled off without the changes in flavor that

normally come about from cooking. Chefs have made flavorings using everything from

common vanilla to offbeat items such as “sea” (using sand) and “the woods” (damp dirt

from the forest). Rotovaps can also be used to remove solvents from a food—removing

alcohol to make whiskey essence, water to increase the concentration of fresh-squeezed

juices, or both alcohol and water to make sauces such as port syrup. Unfortunately, commercial rotovaps are expensive, and the

process of distilling foods is heavily regulated. |

In a large

stockpot (6 qt / 6 liter), add the following and sweat the vegetables until they begin

to soften, about 5 to 10 minutes: 2 tablespoons (25g) olive oil 1 (100g) carrot, diced 2 (100g) celery ribs, diced 1 medium (100g) onion, diced

Add: 4 pounds (2kg) bones, such as chicken, veal, or

beef

For bones, look for “chicken backs” in your grocery store. Cover with water and bring to a slow boil. Add aromatic herbs and spices, such as

a few bay leaves, a bunch of thyme, or whatever suits your taste. Try star anise,

ginger root, and cinnamon sticks for something closer to the stock used in Vietnamese

Phở . Simmer for several hours (two to three for chicken bones; six to eight for thicker

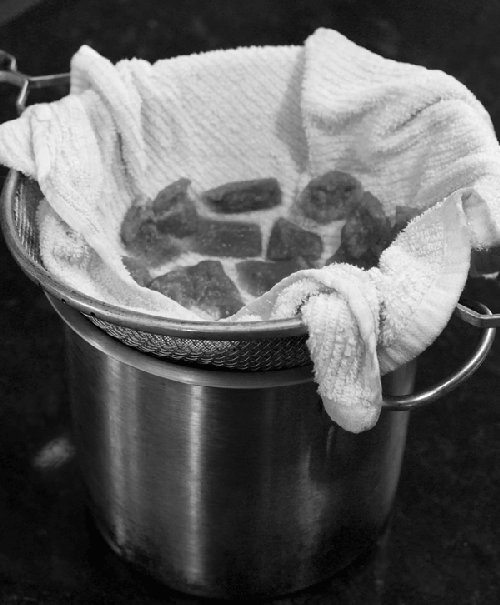

and heavier bones). Strain and cool; transfer to fridge. If you’re worried about leaving the stove on, use a slow cooker. For a bit of overkill, here’s what straining a batch of white stock in various

ways yields, starting with the coarsest straining and going progressively finer. (I

removed the bones and vegetable matter with a ~5,000-micron spider strainer before

running the stock through the 500-micron filter.)

500 micron: stuff caught by a chinois or fine

strainer

...then 300 micron: stuff caught by a cotton towel

...then 100 micron: stuff caught by a Superbag mesh

filter.

|

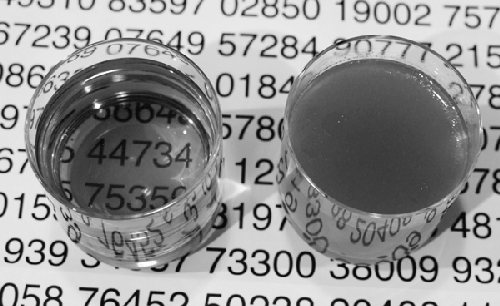

Consommé

made via drip-thawing stock (left), compared to the original stock (right) filtered

at 100 microns. Note the transparency of the consommé—it looks like filtered apple

juice.

To make a drip-filtered consommé, start with a proper stock. The gelatin is a

necessary component, because it serves the same function as the egg-white raft in the

traditional method.

Once the stock has cooled and gelled (leave it overnight), transfer the gelatin to

the freezer and let it freeze solid. As the water in the stock freezes, it will push

the impurities into the gelatin. After it’s frozen, put the stock into a filter bag or

strainer lined with a cotton towel and let it drip-thaw on the counter for an hour, or

in the fridge overnight. The filter or towel will hold on to the gelatin, and the

gelatin will hold on to the smaller particles.

Make sure the container you freeze the stock in is smaller than the filter bag you

use; otherwise, you won’t be able to fit the frozen block into the filter.

Place frozen stock in a strainer lined with a cotton towel. You can

freeze the stock in ice cube trays, as shown here.

After an hour or two, the stock will have thawed, with the consommé

in the pan and the cotton holding on to these weird blob shapes of

gelatin.