3. “Cooking” with Cold: Liquid Nitrogen and Dry Ice

Common and uncommon cold

temperatures.

Okay, strictly speaking, cooking involves the application of heat, but “cooking” with

cold can allow for some novel dishes to be made. And liquid nitrogen and dry ice can be a

lot of fun, too!

If there’s one food-related science demo to rule them all, ice cream made with liquid

nitrogen has got to be the hands-down winner. Large billowy clouds, the titillating

excitement of danger, evil mad scientist cackles, and it all ends with sugar-infused dairy

fat for everyone? Sign me up.

While the gimmick of liquid nitrogen ice cream never seems to grow old (heck, they

were making it over a hundred years ago at the Royal Institution in London), a number of

more recent culinary applications are moving liquid nitrogen (LN2,

for those in the know) from the “gimmick” category into the “occasionally useful”

column.

3.1. Dangers of liquid nitrogen

But first, a big, long rant about the dangers of liquid nitrogen. Nitrogen, one of

the noble gases, is inert and in and of itself harmless. The major risks are burning

yourself (frostbite burn—it’s cold!), suffocating yourself (it’s not oxygen), or blowing

yourself up (it’s boiling, which can result in pressure buildup). Let’s take each of

those in turn:

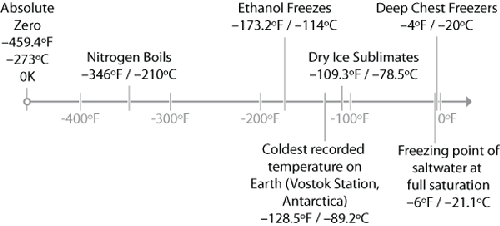

It’s cold. Liquid nitrogen boils at –320°F / –196°C. To put

that in perspective, it’s further away from room temperature than oil in a deep-fat

fryer: seriously cold. Thermal shock and breaking things are very real concerns with

liquid nitrogen. Think about what can happen when you’re working with hot oil, and

show more respect when working with liquid nitrogen. Pouring 400°F / 200°C oil into

a room-temperature glass pan is not a good idea (thermal

shock), so avoid pouring liquid nitrogen into a glass pan. Splashes are also a

potential problem. A drop of hot oil hitting your eye would definitely not be fun, and the same is true with a

drop of liquid nitrogen. Wear closed-toed shoes and eye protection. Gloves, too.

While the probability of a splash is low, the error condition isn’t pleasant.

It’s not oxygen. This means that you can asphyxiate as a

result of the oxygen being displaced in a small room. When using it, make sure

you’re in a relatively well-ventilated space. Dorm rooms with the door closed = bad;

big kitchen space with open windows and good air circulation = okay.

It’s boiling. When things boil, they like to expand, and

when they can’t, the pressure goes up. When the pressure gets high enough, the

container fails and turns into a bomb. Don’t ever store liquid

nitrogen in a completely sealed container. The container will

rupture at some point. Ice plugs can form in narrow-mouthed openings, too, so avoid

stuffing things like cotton into the opening.

“Yeah, yeah,” you might be thinking, “thanks, but I’ll be fine.”

Probably. But that’s what most people think until they’re posthumously

(post-humorously?) given a Darwin Award. What could possibly go wrong once you get it

home? One German chef blew both hands off while attempting to recreate some of Chef

Heston Blumenthal’s recipes. And then there’s what happened when someone at Texas

A&M removed the pressure-release valve on a large dewar and welded the opening shut.

From the accident report:

The cylinder had been standing at one end of a ~20’ × 40’ laboratory on

the second floor of the chemistry building. It was on a tile-covered, 4–6″ thick

concrete floor, directly over a reinforced concrete beam. The explosion blew all of

the tile off of the floor for a 5’ radius around the tank, turning the tile into

quarter-sized pieces of shrapnel that embedded themselves in the walls and doors of

the lab... The cylinder came to rest on the third floor leaving a neat 20″ diameter

hole in its wake. The entrance door and wall of the lab were blown out into the

hallway. All of the remaining walls of the lab were blown 4 to 8″ off of their

foundations. All of the windows, save one that was open, were blown out into the

courtyard.

Do I have your attention? Good. End rant.

Okay, I promise to be safe. Where do I get some?

Look for a scientific gas distributor in your area. Some welding supply stores also

carry liquid nitrogen.

You’ll need a dewar—an insulated container designed to handle

the extremely cold temperatures. Depending upon the supplier, you may be able to rent

one. Dewars come in two types: nonpressurized and pressurized. Nonpressurized dewars are

essentially large Thermoses. The pressurized variety has a pressure-release valve,

allowing the liquid nitrogen to remain liquid at higher temperatures, increasing the

hold time.

Unless you’re renting dewars and having them delivered to your location, stick with

a non-pressurized one. Small quantities of liquid nitrogen in nonpressurized dewars

don’t require hazmat licenses or vehicle placarding when properly secured and

transported in a private car. It’s still considered hazardous material though, because

handled improperly, it can cause death. Transportation falls under “material of trades”

and it is your responsibility to understand the regulations. For example, New York State

defines anything under 30 liters / 8 gallons as a small quantity.

Note:

Standard lab safety protocols for driving small quantities of liquid nitrogen

around usually state that two people should be in the car and that you should drive

with the windows down or at least cracked.

When it comes to working with liquid nitrogen, I find it easiest to work with a

small quantity in a metal bowl placed on top of wooden cutting board. Keep your eyes on

the container, and avoid placing yourself in a situation where, if the container were to

fail, you would find yourself getting splashed.

Don’t sit at a table while working with it. Standing is probably a good general rule

to reduce chances of injury. And remember: it’s cold! Placing a noninsulated container

such as a metal bowl directly on top of countertops, especially glass ones, is not a

good idea.

Note:

I once cracked a very nice countertop with an empty but still cold bowl during a

demo at a large software company whose name begins with the letter M. I’m

still sheepishly apologizing for it.

One final tip: when serving guests something straightaway after contact with liquid

nitrogen, check the temperature (using an IR thermometer) to make sure the food is warm

enough. (As a guideline, standard consumer freezers run around –10°F / –23°C.)