1. How Informational Interviewing Can Help with Career Goals

Don’t worry if your child’s initial career

goal seems unrealistic or out of reach. Most young people have an

extremely limited view of what’s “out there.” Research suggests that

most teenagers think they will enter one of 12 careers, most of which

are in the professional ranks. These careers are doctor, lawyer,

business executive, teacher, athlete, engineer, nurse, accountant,

psychologist, architect, musician, and actor/director. Because these

careers account for less than 20 percent of all jobs in the U.S.

economy, with doctor and lawyer accounting for less that 1.3 percent of

all jobs, many young people will not achieve their stated goal.

This does not mean they are doomed to a life

of drudgery if they don’t achieve their initial goal. It means they

need to identify a wider range of careers. They need to develop a Plan

B.

Informational interviews help your child do

this. They help your child validate or reject an initial career idea.

They lead to related career ideas for exploration. They provide

information about the values important to your child and the activities

that seem interesting. They expand your child’s self-understanding by

holding up a “mirror” of an adult who is working in a career day to

day. They lead to new contacts for informational interviews.

Here is how the informational interview process played out for Megan:

“When I went to college, I didn’t know what I

wanted to do. I was interested in so many things—it was hard to choose.

I thought about being a doctor and about being a teacher. I also

thought about being a businesswoman.

“I started to talk to people about what they

did for a living. I think my dad set up a couple of interviews for me

in the beginning, and I just continued from there. I ruled out doctor

because I decided that it would be hard to have kids with that kind of

lifestyle. I thought about teaching, but after talking to several

teachers it seemed like I wouldn’t be learning enough new things on the job, that you kind of taught the same content each year with some variation.

“I really wanted to be a physician’s

assistant, but the college I was attending didn’t have a program in

that area. All the while I was talking to people, I kept taking those

little career tests on the Internet that told you what you would be

good at. I looked at Web sites that told you what the “hot” jobs were

supposed to be in the next 10 years.

“Course-wise, I just took the basics my first

year in college while I figured out what I wanted to do. By the first

semester of my sophomore year in college, I still hadn’t decided, so I

sat down and asked myself, ‘What have you learned about yourself in all

your conversations so far? Is there anything that might combine all the

things that interest you?’

“I kept coming back to speech therapy. I had

talked to several speech therapists during my research. I knew that as

a speech therapist I could work with a wide variety of people, from

babies to the elderly. I would constantly be learning new things. I

could work in clinical practice and later go on to teach if I wanted to

or open my own business as a speech therapist. It looked like there

would always be jobs in this field. While my income level would

eventually plateau—I wasn’t going to get rich as a speech therapist—it

looked like I would always have a job, one that could be part-time when

I had kids. So that’s what I decided to do. I got a bachelor’s degree

in communication disorders and went on to get my master’s.

“I think the key was just talking to lots and lots of people. All in all, it worked out for me really well.”

Informational interviewing isn’t rocket

science. It’s simply a matter of going out and talking to as many

people as possible about different careers and seeing where those

conversations lead next. Each informational interview will generate new

ideas. It’s like going to the public library and looking through the

stacks.

In addition to directing your child

to new career ideas, informational interviewing will give your child a

more accurate view of the job market. This will enable her to make more

informed decisions and you to control college costs.

2. What Does the Job Market Look Like?

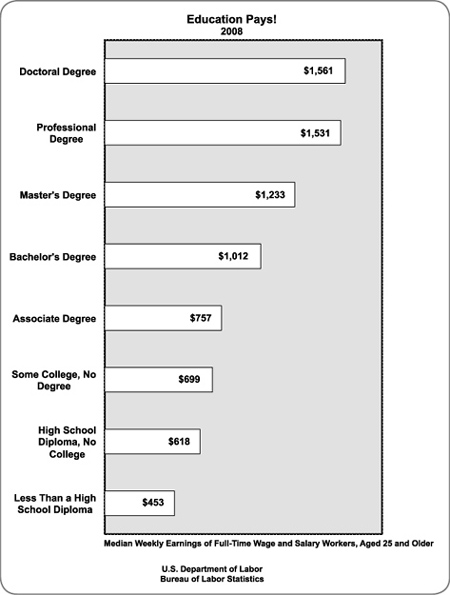

Most young adults have a very one-sided picture of the job market. This view of the job market (Chart 1) shows them that education pays.

Chart 1: Median weekly earnings of full-time workers, 2008.

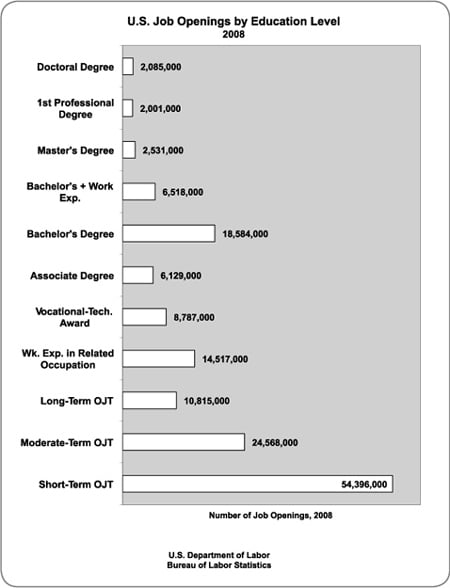

What young people don’t

have is a picture of the actual distribution of job openings in the

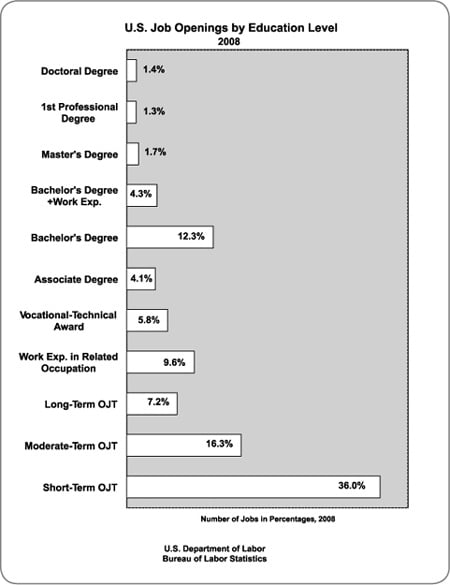

U.S. economy by education and training level. Charts 2 and 3 show the actual distribution of jobs in the United States in 2008.

Chart 2: U.S. jobs by education level, 2008.

Chart 3: U.S. job openings by education level in percentages, 2008.

The fact is that 52

percent of all jobs in the United States in 2008 required only

short-term (less than one month) to moderate-term (one to twelve

months) informal or on-the-job training (OJT).

Another 26 percent of all jobs in 2008

required technical training ranging from long-term OJT (1–5 years OJT,

in-house training, or apprenticeship) to an associate degree.

Twenty-one percent of all jobs in 2008

required a bachelor’s degree or higher. Less than 4.5 percent of jobs

required a master’s degree or higher. The median earnings of all

full-time U.S. workers in 2008 were $32,390 per year, or $15.57 per

hour. Half of all workers made more than this amount and half made less.

Both you and your child need to understand

that this is the job market your child will face. Only then will you be

able to help your child make realistic and effective plans. While there

are many exciting career opportunities today, they will be open only to

young people with the right combination of education, work experience,

and people skills to do the jobs employers want done.

It is important to understand that the BLS

Jobs by Education Level data on in 2008 reflects the education and

training that the BLS and industry experts say is necessary for

proficient performance of the job. It does not reflect the level of

education of people actually doing the job.

The level of education of individual workers

is sometimes higher and sometimes lower than the job requires. An

example would be a computer programmer (bachelor’s degree training

required) who entered the computer field 25 years ago without a degree

and worked up through the ranks. At the same time, a bachelor’s degree

computer programmer whose job was shipped to India in 2001 may now be

working as a sales clerk in a home improvement store. This job requires

only short-term OJT. According to the 2008 BLS data, more than 6.3

million adults with a bachelor’s degree or higher were working in jobs

requiring only short-term OJT. This is called “underemployment.”

Chances are the distribution of jobs presented in Chart 2

is not what you expected. With all the pressure on young people to get

a college degree, you probably expected more bachelor’s degree jobs to

be out there. You have watched well-paying manufacturing jobs being

shipped overseas or eliminated by technology over the past 25 years,

and you have placed your hopes for your child achieving a middle-class

lifestyle on her earning a four-year bachelor’s degree. And you are

willing to borrow increasingly large sums of money to help your child

achieve this goal.

The truth is that many

young people who start college leave without achieving their stated

educational goal. Seventy percent of high school graduates enroll in

college within two years of graduating from high school. Most of these

students intend to get a bachelor’s degree or higher. More than half of

all students who start college leave without completing a degree or

certificate. At a community college, the number of students who leave

without earning a degree or certificate can climb as high as 75

percent. Many young adults, especially those without a career plan or

focus, will try college, drop out, and drift down into the economy.

They will end up working in jobs requiring only short-term or

moderate-term OJT because this is where the majority of jobs are.

What can you, as a parent, do to help your child achieve a positive outcome after high school?

You can encourage your child to

spend as much time researching careers and industries as researching

colleges. You can help your child gather accurate, real-world

information to inform her decisions. You can help her connect with

people who work in a variety of careers and industries to find out what

is going on. The easiest way to do this is through informational

interviewing.