Pray

Religion is part and parcel of daily life

here. To really feel part of it, you need to get up early. In Bahir Dar I was

up and out by 5am, in time to hear the call to prayer from the mosque and to

see the Orthodox Christians appear, wrapped in white muslin, in the dusk as

they made their way to church to say their morning prayers. At Debre Zeit I

walked up a hill at sunrise to the Orthodox Church in the local village and was

in time to see the villagers perform this morning ritual. It was brief – a

touch, a bowed head and a prayer at the shrine outside the church – but it was

clear that this is how they have begun their days for centuries.

the

Orthodox Christians

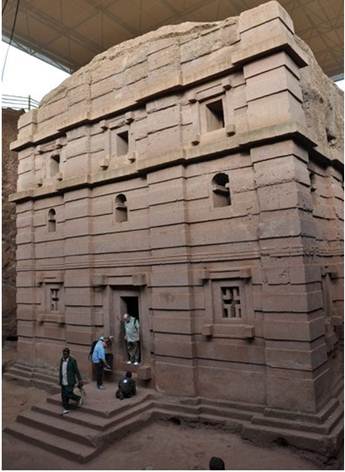

One of the biggest tourist attractions, and a

UNESCO World Heritage Site, is the 11 rock-hewn churches at Lalibela, a

dirt-poor mountain village eking out a living from tourism and subsistence

farming. Flying to this popular town on Ethiopia’s ‘religious route’ has its

own reward: breathtaking views of the Rift Valley. With our guide, Waceh, who

is surely the coolest deacon in Africa, we visited four of the churches near

the town. All 11 churches have been chiselled by hand from single monoliths or

hewn from the vertical limestone cliff faces, a process that took more than 20

years per church. The last one to be carved out, and the most beautiful, is St.

George’s which has its floor over 12 metres below ground level. Although King

Lalibela built all the others, St. George’s was built by his window in his

memory. The perfect geometry and symmetry make it striking in its simplicity.

But what struck me most about these miracles of determination, devotion and

craftsmanship is that these 13th century places of worship are used as churches

to this day. In fact, the footpath to St. George’s passes a handful of tukels

(stone and thatch huts) that make up a school for young boys aspiring to be

monks.

a

UNESCO World Heritage Site, is the 11 rock-hewn churches at Lalibela

Similarly, 19 monasteries scatered around the

37 islands in Lake Tana are also still in use and home to small communities of

monks. The path to the 14th century Ura Kidane Mehret on Zege peninsula is

uphill and uneven, and the monastery is a round mud and straw building that has

survived unbelievably well. The brightly coloured, well-preserved frescoes are

astounding – and with no visible protection other than a request not to use

flash photography.

More than once I was pleasantly surprised by a

young, modern Ethiopian’s display of religiousmess: one girl who escorted our

group wherevr we went wore body-hugging mini-dresses every day but had a cross

on the back of her BlackBerry and prayed devoutly at all the churches we

visited. Orthodox Christianity and Islam – by far the biggest religions amond

Ethiopia’s 80 million people – live side by side and are a matter of course as

the people go about their business.

the

League of Nations

Although not a deity, Emperor Haile Selassie

is respected and revered by many. He was nowhere near perfect but as the 225th

and last emperor of the 3 000-year-old monarchy, he did manage to lead the

country into the 19th, if not the 20th, century. He also called the first

meeting of the Organisation of African Unity (today’s African Union) in 1963.

Selassie completed construction work on the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity, one

of Addis Ababa’s undeniable attractions and the site of his eventual resting

place, after the Italian accupation in 1942. The murals depicting his return to

Ethiopia from exile and address to the then League of Nations sitting alongside

the typical religious ones are an indication of Selassie’s place in Ethiopian

history.