In the 17th century the focus

of the rapidly growing city shifted from the medieval centre, around

Plaza de la Paja, to Plaza Mayor. Part market, part meeting place, this

magnificent square was, above all, a place of spectacle and popular

entertainment. No one knew what the populace wanted better than the

playwrights of Spain’s Golden Age, whose names are still commemorated in

the streets around Calle de las Huertas where many of them lived. There

were no permanent theatres in those days; instead, makeshift stages

were erected in courtyards. Over time the houses deteriorated into slums

and teeming tenements. The parishes to the south of Plaza Mayor were

known as the barrios bajas

(low districts), because they were low-lying and were home to Madrid’s

labouring classes. Mingling with the slaughterhouse workers and tanners

of the Rastro were market traders, builders, innkeepers and horse

dealers, as well as the criminal underclass.

|

When the future patron

saint of Madrid died around 1170 he was buried in a pauper’s grave.

But, in the 17th century, an unseemly rivalry developed between the

clergy of San Andrés and the Capilla de San Isidro over the custody of

his mortal remains. The wrangle dragged on until the 18th century when

the body of the saint was interred in the new Catedral de San Isidro

where it has remained ever since.

|

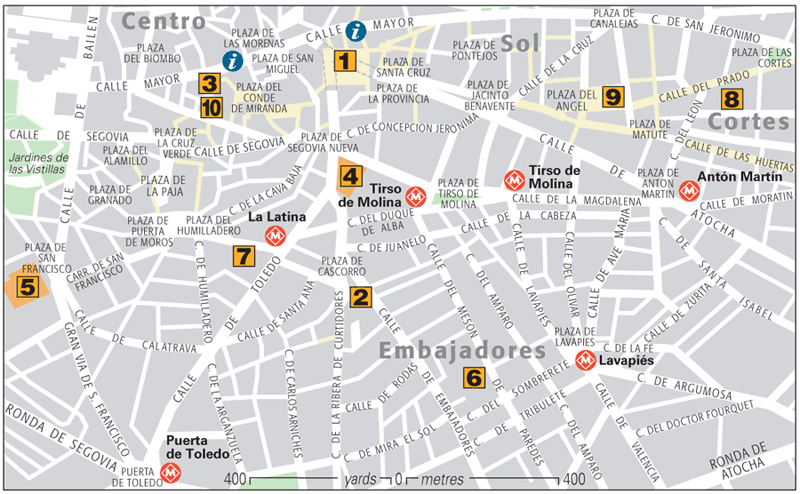

Sights Plaza Mayor The heart of Old Madrid is this vast square, surrounded by arcaded buildings, now home to tourist shops .

Plaza Mayor

El Rastro You

can easily lose a day wandering around the quirky stalls of the city’s

flea market and watching the bustling world go by in the many bars and

cafés .

Plaza de la Villa This historic square off Calle Mayor has been the centre of local government since medieval times. Opposite the Casa de la Villa,

is the Casa y Torre de los Lujanes, Madrid’s oldest civil building

(15th-century). In the centre of the square is a statue of Alvaro de

Bazán, the Spanish admiral who defeated the Turks at Lepanto in 1571 .

Erected in the late 19th century, it is by sculptor Mariano Benlliure.

The palace on the south side is the Casa de Cisneros (1537), built for

one of Spain’s most powerful families. Museo de los Origenes Casa de San Isidro The

museum is housed in an attractive 16th-century palace which once

belonged to the Counts of Paredes. The original Renaissance courtyard is

best viewed from the first floor where archaeological finds from the

Madrid region are exhibited, including a Roman mosaic floor from the 4th

century. Downstairs, the highlights include wooden models of the city

and its royal palaces as they would have appeared in the 17th century, a

short film bringing to life Francisco Ricci’s painting of the 1680 auto-de-fé and the San Isidro chapel built near the spot where the saint is said to have died.

Museo de los Origenes Casa de San Isidro

San Francisco el Grande Legend

has it that this magnificent basílica occupies the site of a monastery

founded by St Francis of Assisi in the 13th century. Work on the present

building was completed in 1784 under the supervision of Francesco

Sabatini. The focal point of the unusual circular design is the

stupendous dome, 58 m (190 ft) high and 33 m (110 ft) in diameter. After

30 years of painstaking restoration, the 19th-century ceiling frescos,

painted by leading artists of the day, are now revealed in their

original glory. Take the guided tour to be shown other artistic

treasures, which include paintings by artists Zurbarán and Goya (chapel

of San Bernardino) and the Gothic choir.

San Francisco el Grande

Lavapiés This

colourful working class neighbourhood has a cosmopolitan feel, thanks

to its ethnic mix of Moroccans, Indians, Turks and Chinese. The narrow

streets sloping towards the river from Plaza Tirso de Molina are full of

shops selling everything from cheap clothes and leather handbags to tea

and spices. Check out the traditional bars, such as Taberna Antonio Sánchez for example. Performances of the traditional light opera known as zarzuela are given outdoors in La Corrala in summer.

Mural, Lavapiés

Lavapiés district

La Latina Historic

La Latina really comes alive on Sundays when the trendy bars of Cava

Baja, Calle de Don Pedro and Plaza de los Carros are frequented by pop

singers, actors and TV stars. Plaza de la Paja – the main square of

medieval Madrid – takes its name from the straw which was sold here by

villagers from the across the River Manzanares. Nowadays it’s much

quieter and a nice place to rest one’s legs. The two churches of San

Andrés and San Pedro el Viejo have been recently restored. Their history

and that of the area as a whole is admirably explained in the Museo de

San Isidro (see Museo de los Origenes Casa de San Isidro).

Façade, La Latina

Casa Museo de Lope de Vega The

greatest dramatist of Spain’s Golden Age lived in this roomy, two

storey brick house from 1610 until his death in 1635. Lope de Vega

started writing at the age of 12 and his amazing tally of 1,500 plays

(not counting poetry, novels and devotional works) has never been

beaten. He became a priest after the death of his second wife in 1614,

but that didn’t stop his compulsive philandering which led to more than

one runin with the law. To tour the restored house with its heavy wooden

shutters, creaking staircases and beamed ceilings, is to step back in

time. You get to see the author’s bedroom, and the book-lined study

where he wrote many of his plays. The women of the house gathered in the

adjoining embroidery room – the heavy wall hangings were to keep out

the cold. Other evocative details include a cloak, sword and belt

discarded by one of Lope’s friends in the guest bedroom. Plaza de Santa Ana The streets around this well-known square boast the greatest concentration of tapas

bars in the city and it’s often still buzzing at 4am. The stylish hotel

ME Madrid dominates the square, and there is an amazing view from its

penthouse bar of the Teatro Español opposite.

Casa de la Villa For

hundreds of years Madrid’s town council met in the church of San

Salvador (since demolished) but in 1644 it was decided to give them a

new, permanent home. The Town Hall was completed 50 years later. Its

main features – an austere brick and granite façade, steepled towers and

ornamental portals – are typical of the architectural style favoured by

the Hapsburgs. Juan de Villanueva added the balcony overlooking Calle

Mayor so that Queen María Luisa could watch the annual Corpus Christi

procession. Highlights of the tour include the gala staircase, hung with

tapestries designed by Rubens; the reception hall with its painted

ceiling and chandelier; the 16th-century silver monstrance carried in

the Corpus Christi procession; the courtyard with stained glass ceiling;

and the debating chamber with frescoes by Antonio Palomino.

|