|

This area has always been a

contrasting mix of the highest and the lowest, from the most extravagant

luxury to the toughest work-a-day world. In ancient times, the

emperor’s lavish palaces were built on the Palatine, but they weren’t

far from the docks, where roustabouts heaved the tons of goods that were

imported to the wealthy city from around the world. There are three

hills in the zone: the Palatine and the Aventine are two of the original

seven, but Monte Testaccio is entirely man-made. Legend has it that the

Aventine was where Remus formed a populist settlement, to rival his

twin brother Romulus’s dictatorial encampment .

Over the centuries it has been an area inhabited by poor workers and

religious institutions. Today, it has returned to being an enclave of

greenery and smart dwellings, studded with hidden art treasures and some

of the world’s finest ancient monuments and priceless archaeological

finds.

|

The ceaseless struggle between the governing and

the working classes is typified by the history of this area. Romulus on

the Palatine versus Remus on the Aventine gave rise to patricians and

plebeians respectively. The contrast still exists, between wealthy

Aventine and down-to-earth Testaccio.

|

|

Carry a bottle of water with you, which you can refill at little fountains around the area

|

|

|

Take a torch (flashlight) and binoculars when visiting churches to see the architectural details close up

|

|

SightsRoman Forum and Palatine Hill Once

the heart of the Roman empire, this mass of ruins is an eerie landscape

that seems gripped by the ghosts of an ancient civilization .

Colosseum and Imperial Fora These

monuments memorialize Imperial supremacy. The Forum of Trajan was

declared a Wonder of the World by contemporaries; the only remnant is

Trajan’s Column, considered to represent Roman sculptural art at its

peak. The Colosseum embodies the Romans’ passion for brutal

entertainment . Musei Capitolini Notwithstanding

their great beauty, the original motivation for these museums was

purely political. When the popes started the first museum here in 1471,

it laid claim to Rome’s hopes for civic autonomy – the Palazzo dei

Conservatori was the seat of hated papal counsellors, who ran the city

by “advising” the Senators. Today the museums are home to a spectacular

collection of art .

Santa Sabina This

church was built over the Temple of Juno Regina in about 425 to honour a

martyred Roman matron. In 1936–8 it was restored almost to its original

condition, while retaining 9th-century additions such as the

Cosmatesque work and the bell tower. Twenty-four perfectly matched

Corinthian columns are surmounted by arcades with marble friezes and

light filters through the selenite window panes. The doors are

5th-century carved cypress, with 18 panels of biblical scenes, including

the earliest known Crucifixion – strangely without any crosses.

Santa Sabina

Baths of Caracalla Inaugurated

in 217 and used until 546, when invading Goths destroyed the aqueducts.

Up to 2,000 people at a time could use these luxurious thermae. In general, Roman baths included social centres, art galleries, libraries, brothels and palestrae

(exercise areas). Bathing involved taking a sweat bath, a steam bath, a

cool-down, then a cold plunge. The Farnese family’s ancient sculpture

collection was found here, including Hercules, a signed Greek original. Today, ruins of individual rooms can be seen.

Capital, Baths of Caracalla

Gymnasia, Baths of Caracalla

Piazza of the Knights of Malta Everyone

comes here for the famous bronze keyhole view of St Peter’s Basilica,

ideally framed by an arbour of perfect trees .

However, it’s also worth a look for the piazza’s wonderful 18th-century

decoration by Giambattista Piranesi, otherwise renowned for his

powerful engravings of fantasy-antiquity scenes. To honour the ancient

order of crusading knights (founded in 1080), the architect chose to

adorn the walls with dwarf obelisks and trophy armour, in the ancient

style. Originally based on the island of Rhodes, then Malta, the knights

are now centred in Rome. San Saba Originally

a 7th-century oratory for Palestinian monks fleeing their homeland, the

present church is a 10th-century renovation, with many additions. The

portico of the beautiful 15th-century loggia houses a wealth of

archaeological fragments. Greek style in floorplan, with three apses,

the interior decoration is mostly Cosmatesque.

The greatest oddity is a 13th-century fresco showing St Nicholas about

to toss a bag of gold to three naked girls lying on a bed, thus saving

them from prostitution. Piazza Gian Lorenzo Bernini 20 Open 8am–noon, 4–7pm Mon–Sat, 9:30am–1pm, 4–7:30pm Sun

Free

Portico carving, San Saba

Pyramid of Caius Cestius This

12 BC edifice remains a truly imposing monument to the wealthy Tribune

of the People for whom it was built. It stands 36 m (118 ft) high and

took 330 days to erect, according to an inscription carved into its

stones. Unlike Egyptian originals, however, it was built of brick then

covered with marble, which was the typically pragmatic, Roman way of

doing things.

Pyramid of Caius Cestius

San Teodoro At

the foot of the Palatine, this small, circular, 6th-century church is

one of Rome’s hidden treasures. St Theodore was martyred on this spot,

and his church was built into the ruins of a great horrea

(grain warehouse) that stood here. The apse mosaic showing Christ

seated upon an orb is original, but the Florentine cupola (1454) and

other treatments are mostly 15th-century restorations ordered by Pope

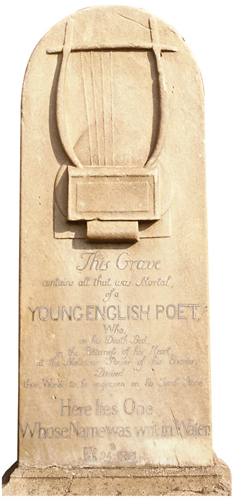

Nicholas V. The courtyard was designed by Carlo Fontana in 1705. Protestant Cemetery Also

called the Acattolica (Non-Catholic) Cemetery, people of many faiths

have been sepulchred here since 1738. The most famous denizens are the

English poets Keats and Shelley . Until 1870, crosses and references to salvation were forbidden.

Keats’ tombstone

|