Your health will suffer if your body is

overly acidic. But you can control it through diet. We show you how.

We in the West have turned a deaf ear to

the wisdom of the ancients: that the most effective antidote to illness is in

nature’s larder. Instead of stocking up on the seasonal, fresh, unrefined foods

that our bodies crave, we gorge on fat, starch, sugar, salt and chemicals when

we become ill.

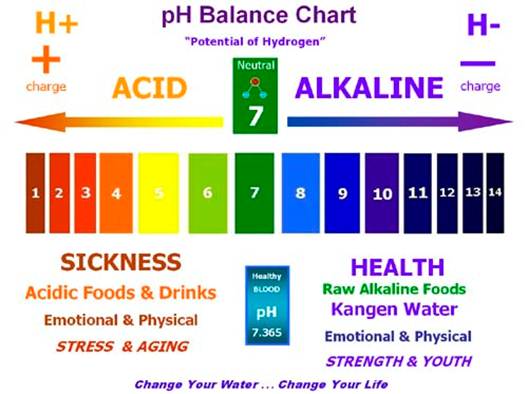

In

its natural state the pH of the body is slightly alkaline. It must maintain

this for optimal good health

Remedies to cure the effects of bad

nutrition inevitably include some fact, fiction, good sense and

let’s-jump-on-the-bandwagon fads. The acid/alkaline diet sounds like just

another catchy title for a bestseller, but behind the hype there are guidelines

rooted in a simple truth: we are what we eat.

What is the acid/ alkali balance?

The acid/ alkali balance depends on the

concentrate of hydrogen ions in the body, which in turn determines the pH

(power of hydrogen) of the blood. The scale to measure pH goes from one (most

acid) to 14 (most alkaline). For proper cell function, the pH of blood must be

in the narrow, slightly alkaline range of 7.35-7.45.

The body regulates pH automatically, but

it’s these small imbalances that we refer to when we talk about being acidic.

It would take trauma or an illness, such as kidney failure, to cause a major

fluctuation in pH balance, resulting in a nasty condition known as metabolic

acidosis.

“There are many forms of acidosis,” explains

dietitian Cornelia Owens, from the Nutritional Information Centre at the

University of Stellenbosch (NICUS). “Metabolic acidosis is associated with a

decrease in alkalinity (also called “base”), when there is a drop in the level

of bicarbonate in the fluid outside the veins and arteries. This kind of

disruption is serious. Treatment is essential as the results can range from

electrolyte imbalances to metabolic mayhem and death”

How is pH balance regulated?

“The body has three sophisticated

mechanisms to regulate the pH,” says Owens. “The kidneys do it through hydrogen

secretion and bicarbonate resorption. The lungs regulate it by altering either

the rate or depth of breathing in order to retain carbon dioxide, which is

alkaline. And then there’s a process called buffering, in which alkali reserves

in the cells are used to counter the large amounts of acid produced through the

food we eat and through normal tissue metabolism”

It’s this third area where diet makes a

difference. Regardless of what we eat, the body must maintain the pH balance

for life to be sustained. When food is digested, the residue (also called

“ash”) is either acidic or alkaline. A balanced diet contains the right

proportions of both; if it’s lacking in fruit and vegetables, most of which

have an alkalizing effect, the body will scout around for other sources of

alkali to ensure that the pH remains stable.

Bone has a reliable stock of alkali salts,

but too much plundering of this valuable store will obviously weaken them,

making the person susceptible to osteoporosis and fractures. The American

Journal of Clinical Nutrition reports that a seven-year study conducted at the

University of California on 9 000 women showed that those who have chronic

acidosis are at greater risk for bone loss than those who have normal pH

levels. It found that many of the hip fractures prevalent among middle-aged

women are connected to acidity caused by a diet high in animal foods and low in

vegetables. This is because the body borrows calcium from the bones in order to

balance pH.