… A home birth

As labor begins

If you’re having a home birth, your midwife will have talked to you in advance about how to contact her once you’re in labor.

Since she will be traveling to you, bear in mind local traffic

conditions. If the streets might be busy, it’s worth phoning her in

early labor. She may ask you to phone again when your contractions are

closer together.

While waiting for the

midwife, you may want to move around, or relax in a warm bath. If you’ve

purchased or rented a birthing pool, ensure that this is ready to use.

Ask your partner to lay down old sheets or plastic sheeting over the

floor. Eating small, nourishing snacks and drinking water will provide

energy for the hours ahead.

Home births are not

for everyone. They’re only an option for you if you’re having a healthy,

low-risk pregnancy, and you may need to be transferred to a hospital

before delivery if complications arise. The American College of

Obstetricians and Gynecologists opposes home births because of the

potential for complications, even in low-risk pregnancies, as does the

American Medical Association. Only 6 out of every 1,000 U.S. births are

home births.

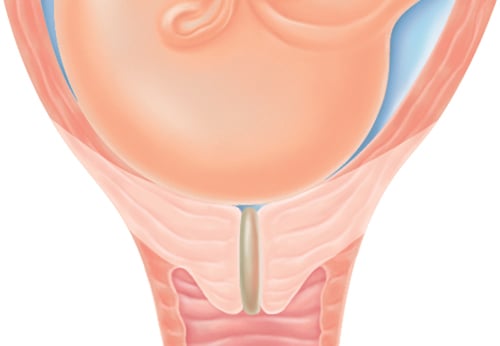

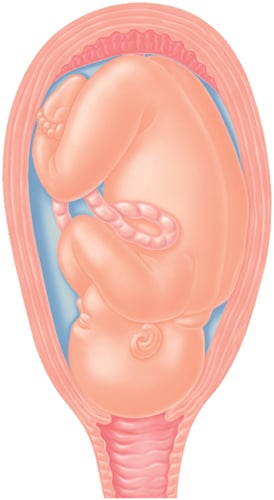

Changes to the cervix

The cervix is comprised of firm muscle that forms a strong base at the bottom of the uterus.

For your baby to be born, the cervix needs to stretch and soften so

that it can open, or dilate, and your baby can pass out of the uterus

and into the vagina.

Toward the end of

pregnancy, substances in your blood called prostaglandins start to

soften the cervix so that it becomes more malleable. While you are

pregnant, your cervix is usually around 2 to 3 cm long. In late

pregnancy or early labor, Braxton Hicks’ practice contractions start to

shorten the cervix, a process known as effacement. Most women have a

cervix that has shortened to 1 cm during the very early stages of labor.

This is also referred to as 50 percent effaced. As the cervix continues

to shorten, the cervix is gradually drawn up by the uterus, and by the

time it is 100 percent effaced, the cervix will have started to open.

Eventually the cervix becomes fully dilated (see Changes to the cervix), and the baby can be pushed out.

As labor approaches, the cervix starts to lose its firmness and starts to soften in response to the presence of prostaglandins in the blood.

Once the cervix has softened, it starts to shorten. This process is referred to as effacement and needs to occur before the cervix can begin to dilate.

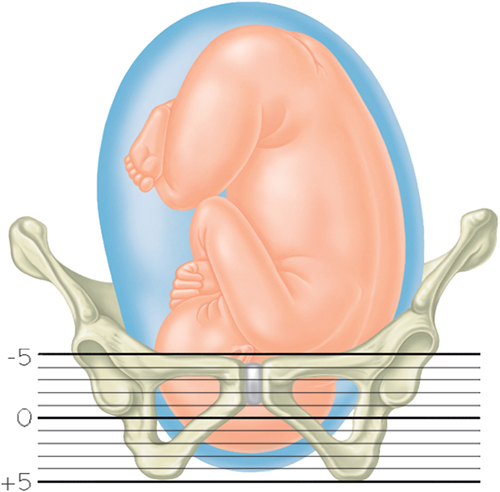

The “station”

The “station” refers to the position of your baby’s head

in relation to your pelvis. This is recorded as a number between -5 and

+5. Zero station means the head is “engaged” and has entered the

vaginal canal within the pelvic bones. A negative number (-5 to 0) means

that the head isn’t engaged in the pelvis. A positive number (0 to +4)

means that your baby’s head is moving down the pelvis and +5 means your

baby is crowning (being born). Ideally, you should not push until the

head is engaged in the pelvis, even if you’re fully dilated.

The position of the head in relation to the pelvis is marked on a scale of -5 to +5.

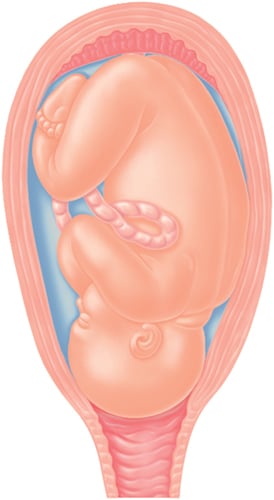

Dilation

Once your cervix is stretched and softened (see Support in the first stage),

it begins to open, or dilate, so that your baby can pass through into

the vagina to be born. Regular contractions cause the cervix to dilate,

and in first labors the cervix dilates at an average of 1 cm per hour;

this rate is often faster for subsequent labors. You cannot push your

baby out until you are fully dilated, which occurs at 10 cm.

At 2 cm dilation, the cervix has shortened and is beginning to open. Contractions may still be irregular.

At 6 cm dilation, you are in active labor. Your contractions will be more frequent, regular, and stronger.

At 10 cm dilation, you are fully dilated. Contractions may be almost continuous and you are nearly ready to start pushing your baby out.

| Q: |

Am I likely to have medical interventions in labor in the hospital?

|

| A: |

The reality of a hospital birth is that medical interventions

may be suggested, some of which may be more helpful than others.

Procedures that can be done include artificially breaking the water;

inserting a catheter or an IV line; and speeding up labor with drugs.

|

| Q: |

Is artificial rupture of the membranes routine in the hospital?

|

| A: |

Artificially breaking the bag of water, known as amniotomy or ARM

is offered routinely in some hospitals in labor. This is a painless,

low-risk procedure that is thought to shorten the time of labor by one

to two hours, reduce the chance of a low early APGAR score in your baby, and significantly decrease the chance that you’ll need drugs to speed up labor . ARM is usually optional. The one time it is necessary is if a fetal scalp electrode needs to be put on the baby’s head (see Scalp electrode) since this cannot be done without breaking the water. It may also be done as part of the induction process .

|

| Q: |

How is labor speeded up with medication?

|

| A: |

A slow labor may be speeded up with the medication oxytocin, a

procedure known as augmentation. Oxytocin is naturally released from

your pituitary gland in labor. Synthetic oxytocin can be given via an

intravenous (IV) line to strengthen contractions. When this is done,

it’s usual to have continuous fetal monitoring (see Electronic fetal monitoring)

since, if the contractions become too strong, your baby may show signs

of distress. Since oxytocin is quickly cleared from your system once the

IV is turned off, contractions that are too strong can be weakened

quickly. Oxytocin is also given during an induction of labor.

|

… Your birth partner

Support in the first stage

During the first stage,

your partner has a varied and important role. In addition to helping

you feel comfortable and assisting you with positions, your partner can

also support you mentally. This is especially important at the end of

the first stage, when you reach transition),

a point when women often feel panicky and out of control. Your partner

can offer reassurance that you’re doing well and that the delivery of

your baby is not far off. He can also improve your comfort, for example

by applying a damp, cool washcloth to your face and neck, and he can

help you focus on your breathing, reminding you to pant or blow to help

you resist the urge to push before the cervix is fully dilated.

Failure to progress in labor

If your cervix is not dilating, or your baby is not descending, as quickly as expected during the first stage,

your doctor will try to assess why this is and if something can be

done. Usually, your doctor will assess the three P’s: the passenger (the

size of the baby and his position in the uterus); the powers (the

efficiency of your contractions); and the passage (the size and shape of

your pelvis). These three elements work together and each one is

important for your labor to progress smoothly.

There are several reasons

why a labor may not progress. These include if the baby’s head is too

large for the mother’s pelvis, known as cephalopelvic disproportion

(CPD); if contractions are inefficient; and if the baby is in a

posterior position with his back facing the mother’s back.

Cephalopelvic disproportion

Sometimes CPD may

be suspected before labor, in late pregnancy. This may be the case if

the doctor thinks that you have a narrow pelvis or a prominent sacral

bone, both of which may make birth slower or more difficult. However, an

assessment of the pelvis alone is not an accurate way to predict if

you’ll be able to have a successful vaginal birth and, even if the

pelvis is not an optimal shape, the doctor may be happy for you to

continue trying for a vaginal birth. This is because it’s not the shape

of your pelvis alone that is important, but the interaction between your

baby (the passenger) and your pelvis.

If CPD is suspected, but

the baby’s head has engaged, a vaginal birth can still be attempted. The

labor will be monitored with a labor graph

and if there are signs that the baby is in distress, an emergency

cesarean may be performed. If the head hasn’t engaged toward the end of

labor, a planned cesarean may be offered.

If your doctor suspects

CPD in labor, she will reassess the baby’s size to check if she

originally underestimated his or her weight. Even though the combination

of a large estimated weight and a slow labor can suggest that there may

be delivery problems, often labor proceeds normally.

Inefficient contractions

If your labor isn’t

progressing because your cervix is dilating slowly or has stopped

dilating, your doctor will assess the frequency of your contractions,

which should be every 2 to 3 minutes. She’ll also assess how strong the

contractions are by palpating your abdomen: the firmer it feels during

contractions, the more likely they are to be effective. If contractions

are more widely spaced than they should be and their strength indicates

they’re unlikely to be effective, she may use one or two techniques to

speed up labor, known as augmenting labor.

First, she may artificially rupture the membranes if they haven’t already ruptured, a process known as ARM . This can shorten the duration of labor by around one to two hours.

If ARM has no effect, you may be given the drug oxytocin to increase the strength and frequency of contractions .

Initially, a small dose is given and then increased over time until

you’re having three or four moderately strong contractions every 10

minutes. If this is done, you’ll have continuous electronic fetal monitoring to check that the baby is not distressed by the sudden onset of stronger contractions.

If your labor is still not progressing several hours after the drugs have been started, then a cesarean may be recommended.

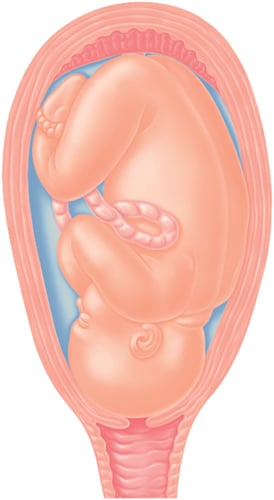

Posterior presentation

The best position for

your baby in labor is an occipito-anterior position with the back of the

head (occiput) facing your front. If the back of the head faces your

back (occipito-posterior) this can make it hard for the baby to turn and

move down the birth canal and can prolong labor. The doctor may suggest

that you change positions to encourage the baby to turn. If the baby

fails to rotate, forceps or vacuum may be needed to aid the delivery .

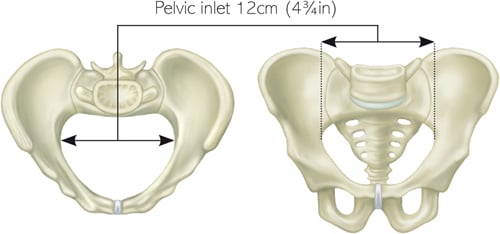

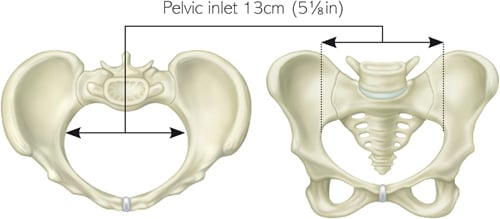

A gynecoid pelvis

is the name given to a pelvis that has a circular shape. The generous

proportions of this more typical “female-shaped” pelvis provides room

for the head to pass through during the birth.

An android pelvis

is the term used to describe a pelvis that has a more triangular shape.

This reduces the room available for the baby’s head to pass through and

is more likely to cause problems during a vaginal delivery.