The USA Rice Federation tells consumers

that there is no reason to be concerned about arsenic in food. Its website

states that arsenic is “a naturally occurring element in soil and water” and

“all plants take up arsenic”.

Grant

Lundberg, a rice producer in Richvale, Calif, has begun extensive testing for

arsenic.

But “natural” does not equal safe.

Inorganic, the predominant form of arsenic in most of the 65 rice products we

analyzed is ranked by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as

one of more than 100 substances that are Group 1 carcinogens. It is known to

cause bladder, lung, and skin cancer in humans, with the liver, kidney, and

prostate now considered potential targets of arsenic-induced cancers.

Though arsenic can enter soil or water due

to weathering of arsenic-containing minerals in the earth, humans are more to

blame than Mother Nature for arsenic contamination in the U.S. today, according

to the federal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. The U.S. is

the world’s leading user of arsenic, and since 1910 about 1.6 million tons have

been used for agricultural and industrial purposes, about half of it only since

the mid-1960s. Residues from the decades of use of lead-arsenate insecticides

linger in agricultural soil today, even though their use was banned in the

1980s. Other arsenical ingredients in animal feed to prevent disease and

promote growth are still permitted. Moreover, fertilizer made from poultry waste

can contaminate crops with inorganic arsenic.

Rice is not the only source of arsenic in

food. A 2009-10 study from the EPA estimated that rice contributes 17 percent

of dietary exposure to inorganic arsenic, which would put it in third place,

behind fruits and fruit juices at 18 percent, and vegetables at 24 percent. A

more complete study by the European Food Safety Authority found cereal products

could account for more than half of dietary exposure to inorganic arsenic,

mainly because of rice.

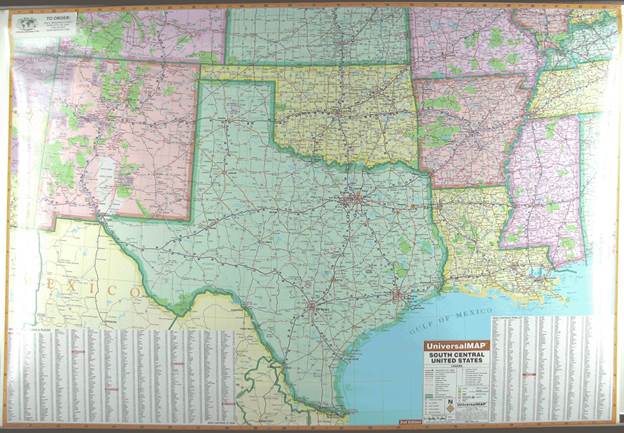

“Extensive

surveys of south central U.S. rice, by more than one research group have

consistently shown that rice from this region is elevated in inorganic arsenic

compared to other rice-producing regions,”

Rice absorbs arsenic from soil or water

much more effectively than most plants. That’s in part because it is one of the

only major crops grown in water-flooded conditions, which allow arsenic to be

more easily taken up by its roots and stored in the grains. In the U.S. as of

2010, about 15 percent of rice acreage was in California, 49 percent in

Arkansas, and the remainder in Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, and Texas.

That south-central region of the country has a long history of producing

cotton, a crop that was heavily treated with arsenical pesticides for decades

in part to combat the boll weevil beetle.

“Extensive surveys of south central U.S.

rice, by more than one research group have consistently shown that rice from

this region is elevated in inorganic arsenic compared to other rice-producing

regions,” says Andrew Meharg, professor of biogeochemistry at the University of

Aberdeen in Scotland and co-author of the book “Arsenic & Rice”. “And it

does not matter relative to risk whether that arsenic comes from pesticides or

is naturally occurring”. High levels of arsenic in soil can actually reduce

rice yield, notes the Department of Agriculture has invested in research to

breed types of rice that can withstand arsenic. That may help explain the

relatively high levels of arsenic found in rice from the region, though other

factors such as climate or geology may also play a role.

What our tests found

Within brands, brown rice had higher arsenic

than white

We tested 223 samples of various rice

products that we bought mostly in April and May, many from stores in the New

York metropolitan area and online retailers. The samples covered a variety of

rice-containing food categories, including infant cereals, hot cereals,

ready-to-eat cereals, rice cakes, and rice crackers. We bought products often

used by people on gluten-free or other special diets, including rice pasta,

rice flour, and rice drinks.

Within brands, brown rice had higher arsenic than

white

We tested at least three samples of the

foods and beverages for total arsenic. We measured specific levels of inorganic

arsenic. And we checked for two forms of organic arsenic, called DMA and MMA.

Though inorganic arsenic is considered the

most toxic, concerns have been raised about potential health risks posed by

those two organic forms, which the International Agency for Research on Cancer

has labeled “possibly carcinogenic to humans”. We found DMA in the 32 rices we

tested which include choices from the south central states and elsewhere,

including California, India, and Thailand.

In brands for which we tested both a white

and a brown rice, the average total and inorganic arsenic levels were higher in

the brown rice than in the white rice of the same brand in all cases. Among all

tested rice, the highest levels of inorganic arsenic per serving were found in

some samples of Martin Long Grain Brown rice, followed by Della Basmati Brown,

Carolina Whole Grain Brown, Jazzmen Louisiana Aromatic Brown, and Whole Foods’

365 Everyday Value Long Grain Brown. But we also found samples of brown rice

from Martin and others with inorganic arsenic levels lower than that in some

white rice.

Though brown rice has nutritional

advantages over white rice, it is not surprising that it might have higher

levels of arsenic, which concentrates in the outer layers of a grain. The

process of polishing rice to produce white rice removes those surface layers,

slightly reducing the total arsenic and inorganic arsenic in the grain.

In brown rice, only the hull is removed.

Arsenic concentrations found in the bran that is removed during the milling

process to produce white rice can be 10 to 20 times higher than levels found in

bulk rice grain.

We also tested for lead and cadmium, other

metals that can taint food. The levels we found were generally low overall.

Based on our recommended limits for rice products, even the few samples with

elevated lead cadmium should not contribute significantly to dietary exposure.

Cereals cause concern.

Worrisome arsenic levels were detected in

infant cereals, typically consumed between 4 and 12 month of age.

Among the four infant cereals tested, we

found varying levels of arsenic, even in the same brand. Gerber SmartNourish

Organic Brown Rice cereal had one sample with the highest level of total

arsenic in the category at 329 ppb, and another sample had the lowest total

level in this category at 97.7 ppb. It had 0.8 to 1.3 micrograms of inorganic

arsenic per serving.

Earth’s Best Organic Whole Grain Rice

cereal had total arsenic levels ranging from 149 ppb to 274 ppb, but higher

levels of inorganic arsenic per serving, from 1.7 to 2.7 micrograms.

So what’s a parent to do? To reduce arsenic

risks, we recommend that babies eat no more than 1 serving of infant rice

cereal per day on average. And their diets should include cereals made of

wheat, oatmeal, or corn grits, which contain significantly lower levels of

arsenic, according to federal information.

To

reduce arsenic risks, we recommend that babies eat no more than 1 serving of

infant rice cereal per day on average.

The EPA sets limits for a carcinogen based

on how many extra cases of cancer would be caused by exposure to the toxin at a

certain level. The limit is designed to minimize that risk. For our

recommendations, we used the latest available science to choose a moderate

level of protection that balances safety and feasibility, similar to the EPA’s

approach for water. Our scientists made these calculations using standard

estimates of weight, typical daily consumption of individual rice products over

a lifetime, and the range of levels of inorganic arsenic we found. For our

recommendation for children, we paid particular attention to their levels of

consumption during this critical phase of their development.

According to federal data, some infants eat

up to two to three servings of rice cereal a day. Eating rice cereal at that

rate, with the highest level of inorganic arsenic we found in our tests, could

result in a risk of cancer twice our acceptable level.

For children and pregnant women, risks are

heightened. Keeve Nachman, Ph.D., a risk scientist at the Center for a Livable

Future in the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, says, “The more

we learn about arsenic’s additional effects on the developing brain, the more

concerned I am by these levels of arsenic being found in infant and toddler

rice cereal.”

Ready-to-eat cereals, which are popular

with adults as well as children, also gave us cause for concern. For instance,

Barbara’s Brown Rice Crisps had inorganic arsenic levels that ranged from 5.9

to 6.7 micrograms per serving. Kellogg’s Rice Krispies, at 2.3 to 2.7

micrograms, had the lowest levels for the category in our tests.

Rice drinks in our tests showed inorganic

arsenic levels of up to 4.5 micrograms per serving. Based on those results, our

scientists advise that children under the age of 5 should not have rice drinks

as part of a daily diet. In the United Kingdom, children younger than 41/2

years are advised against having rice milk because of arsenic concerns.

“This is a time when cells are

differentiating into organs and many other important developmental things are

going on, so getting exposed to a toxicant like arsenic in utero or during

early childhood can cause damage that may not appear until decades later,” says

Michael Waalkes, laboratory chief at the Division of the National Toxicology

Program. He is one of the authors of a June 2012 report funded in part by the

National Institutes of Health that concluded early life exposure to arsenic

produces a wide range of cancers and other diseases.