Behind their charming facades, Britain’s

villages hide many mysteries.

Rose-framed cottages and the ancient church

tower cluster protectively around the oak-shaded green. Here, in summer, the

crack of willow on leather indicates that cricketers are conducting their

weekly ritual, to utter bemusement of foreign visitors. There’s nothing more

English than the village.

Behind

their charming facades, Britain’s villages hide many mysteries.

But how, and why, did villages first appear

in our landscape, and what made people want to congregate in these small,

tightly knit communities, which in many instances have stood for over 1,000

years?

According to pioneering landscape a land of

villages during the 20 generations that made up the Anglo-Saxon period, between

about AD450 and 1066. Most of our villages date back to that time, and their

names reflect this.

Most

of our villages date back to that time, and their names reflect this.

Wherever you see the suffix ‘ham’, for

example, it was originally a Saxon homestead, and if that’s prefixed by an

‘ing’, such as Franglingham, that means it was the ‘ham’ of the family or group

of people, or the dwellers at a specific place, whose names are usually

preserved in the first element of the placename, ie ‘fram’. A ‘tun’ or ton

meant a farmstead, and the many ‘worths’ indicated an enclosure; a ‘burh’ or

borough, a stronghold, and a ‘cot’ or cote, a cottage. Incidentally,

Piddletrenthide, means village on the river Piddle that is worth 30 hides

(medieval land units).

Scandinavian influence

Celtic

villages

The Danish, or Viking, influence, found

mainly in the north and east of England, is often indicated in village names by

the Old Scandinavian suffix “by”, which also means a farmstead; “thorp”, which

means one outside the main settlement, or “thwaite”, which means a clearing.

Before the Saxon period, prehistoric and

Celtic villages were smaller and much more isolated, such as those still found

in the hill country of the north and west. We’d probably call them hamlets

today. Apart from the obvious fact of their size, the main difference between a

village and a hamlet is usually the presence of a church.

The typical Saxon village came about as a

grouping of families in the center of the parish, or around a key natural

feature, such as a village pond. Villagers later had shares in the great open

fields that had been won from the surrounding wildwood by their ancestors.

Strips of land were allocated to each ‘villein’ (free villager) on the three-field

rotation system where, every year, one field is sown with winter wheat; the

second, a spring-sown crop, such as barley, and the third is left fallow to

recover its nutrients. This ancient system is still employed at places Laxton

in Nottinghamshire and Braunton in North Devon.

The

typical Saxon village came about as a grouping of families in the center of the

parish, or around a key natural feature, such as a village pond.

But that chocolate-box picture of a typical

village we started with is far from reality in many British villages. Below, we

take a look at some of our stranger villages, which often tell entirely

different stories. In some cases, they speak of our ancient past, in others,

they reflect more recent aspects of the social and economic history of our

ever-fascinating countryside.

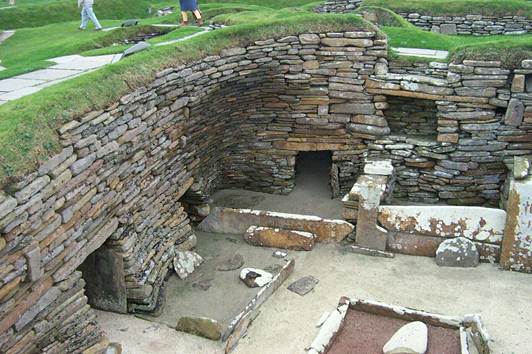

Stone age village

Skara Brae, Orkney.

the

Neolithic village of Skara Brae on Orkney

Visiting the Neolithic village of Skara

Brae on Orkney is rather like dropping in on Fred Flintstone’s home in Bedrock.

There’s something quite magical about stooping through the low entrance chamber

of a hut and seeing the central hearth, dressers and bed chambers of people who

lived here 5,000 years ago. It’s as if they’ve just left, as a huge storm

crashed in from the Atlantic, burying the village of Skara Brae under fine

sand. Skara Brae, sometimes known as the Pompeii of the north, is the

best-preserved Neolithic village in Europe.

Skara Brae is about six mile north of

Stromness.