Bad? Here’s what the latest science

says.

Hidden in Plain Sight

Added sugars lurk in many processed foods.

And although more and more food companies are ditching high-fructose corn

syrup, their products aren’t necessarily sugar-free. In fact, they may contain

just as much sugar as before, just in a different form. Here’s how to find out:

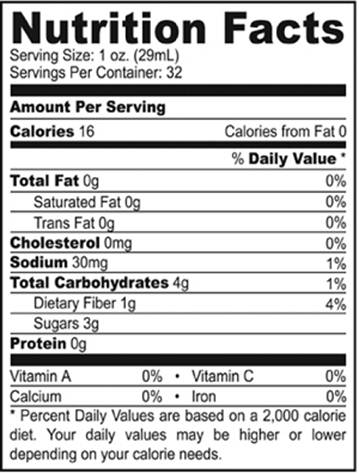

Under a food label’s “sugars” designation,

both natural and added sugars are included.

Natural sugars (such as lactose in milk and

fructose in fruit) are not usually a problem because they come in small doses

and are packed with other nutrients which helps slow absorption

All of these are aliases for added sugar.

The higher up on the list they appear, the more sugar is in the product.

TIP

Determine how much unhealthful added sugar your product contains by comparing

it to a comparable sugar-free product, such as strawberry yogurt to plain

yogurt or canned peaches in syrup to canned peaches in juice.

Much sugar in our bodies might not be a

direct path to health nirvana. Most experts agree that we all cat far too much

of it: rates of obesity have dramatically increased in the U.S. over the past

20 years, and studies have linked drinking large amounts of sugar-sweetened

beverages to increased risk of obesity, especially in children.

But that’s not news.

A new chapter in the history of sugar is

now bursting open and it’s causing many scientists to cringe, the public to pay

attention and lots of folks to wonder whether this is just another false alarm.

This new development in the sugar story is evangelized by one researcher in

particular, a man who says there’s a lot more to the health story than simply

nutrient-empty calories from added sugar making us fat. The researcher, Robert

Lustig, M.D., a pediatric endocrinologist at the University of California, San

Francisco, states it like this, bluntly: “Fructose is a poison.”

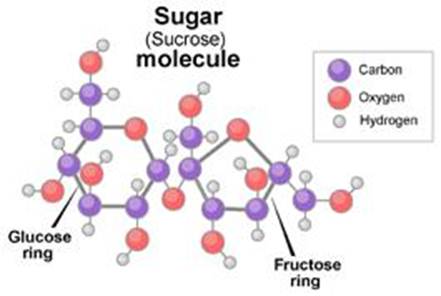

“High-fructose” corn syrup (HFCS), despite its name, and table sugar (sucrose)

are both composed of two smaller sugar molecules, glucose and fructose, in

roughly equal proportions. (HFCS and sucrose arc virtually chemically

equivalent, say most scientists and doctors.) The glucose part is fine, says

Lustig; it’s the body’s preferred fuel, the type that smoothly runs the billions

of cells in our body. But the fructose part “is a chronic poison,” he says. “It

doesn’t kill you after one fructose meal, it kills you after 10,000. The

problem is, every meal now is a fructose meal.” HFCS is being added

surreptitiously to processed foods. It has found its way into everything from

pretzels to ketchup.

Lustig says this mega-shot of fructose from

added sugar uniquely gums up our inner workings and causes in fact, is the

primary cause of metabolic syndrome, the constellation of disorders, including

type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and fatty liver disease, that are

devastating our country. All of this happens, Lustig says, when we’re consuming

too many calories and most Americans are eating 200 to 300 extra calories a

day. He is quick to point out that he only means the fructose found in added

sugar, the super-high levels of sucrose and HFCS we eat in processed foods and

drinks (including fruit juices), not the lower levels found in fiber-rich whole

fruit nor the sugars (lactose) found naturally in milk.

Lustig laid out his hypothesis in a 2009

lecture for the general public called “Sugar: The Bitter Truth” at UC, San

Francisco. The university filmed the charismatic lecturer. The video was posted

on YouTube; it went viral. In 2011, The New York Times Magazine published a

piece by Gary Taubes admiring Lustig’s theory. In 2012, 60 Minutes ran a

segment on toxic sugar featuring Lustig. In December, Lustig will publish a

book on nutrition, Fat Chance (Hudson Street Press), which includes his views

on fructose.

Lustig presents a tempting, epic story of

good versus evil, concluding in both his video and a recent commentary in the

journal Nature that the government should regulate added sugar as it regulates

alcohol. “Fructose is ethanol without the buzz,” he says. And we are riveted:

as of summer 2012, over 2.5 million people had sat down in front of their

computers and watched Lustig’s 90-minute lecture on fructose biochemistry,

which he begins with a sort of arm-around-the-shoulder, conspiratorial tone:

“I’m gonna tell you, tonight, a story.” We crave a good narrative with real

answers almost as much as we love sugar. But does the science actually support

Lustig’s theory?

The Science of Sugar

Tens of thousands of years ago, before

two-liter sodas and oversized candy bars, our tongues rarely tasted sweetness.

Sugar was extremely hard to come by. Honey had it (but it was protected by

bees) and fruit contained it, enveloped in a fiber cage, but otherwise

sweetness was a sensation few people experienced, and only in certain months of

the year.

But because sugar provides safe calories

(almost no plant that tastes sweet is poisonous), we evolved to crave it. Our

brains are hard-wired to release a big shot of joy whenever we taste sweetness,

by unleashing a chemical called dopamine that sparks our brain’s pleasure

center, a region called the nucleus accumbens. We also have a second way to

make sure we are constantly on the lookout for this valuable energy: Even the

thought of sugar makes us happy. The brain releases dopamine before we cat

sugar, while we’re seeking it out and as we anticipate placing it in our

mouths. We have an ancient, always-on, deep-brain need to fill our stomachs

with sweet calories.

Now, rubbing the magic lamp, we’ve finally

gotten our genes’ greatest wish: an endless supply of sugar. In the U.S.,

sucrose can be found all over the supermarket, but, more insidiously,

ubiquitous HFCS is a cheap source of sweetness, a result of subsidies to corn

farmers. “High-fructose corn syrup is evil, but it’s not evil because it’s

metabolically evil; it’s evil because it’s economically evil,” Lustig says in

his YouTube video. Because it’s so cheap it has found its way into nearly every

processed food, including crackers, yogurt, tomato sauce, as well as cookies

and sweetened beverages like sports drinks, juices, sodas.

But, Lustig says, the genie played a trick

on us. Lustig explains the problem with fructose by explaining what happens

when you put one of these processed goodies say, a cracker into your mouth (the

details of this theory were mostly formulated through studies in animals):

First, a bite. Then another bite. Sprinkles of cracker descend into your

stomach and then to your small intestine, where enzymes dissect sucrose

molecules into their constituent parts: glucose and fructose. (HFCS molecules

are not bonded, thus the glucose and sucrose are already free.) Remember,

glucose is the fuel of choice for our bodies; our cells use it or store it

easily even when we cat it in high doses in processed food. Fructose, on the

other hand, cannot by its very nature slip into our body’s cells to make

energy, so almost all of it slides down the portal vein into the liver, the

toxin-processing organ, where it’s dumped (and dumped again, as we eat more

sweetened food).

High

Fructose Corn Syrup (HFCS) = Corn Sugar

What does our liver do with all this second

rate fructose fuel? It can’t store it, so it tries to break it down into

energy. But the cells’ normal energy generating cycle cannot possibly spin fast

enough to process this mountain of fructose, so most of it meanders off into

the liver in the form of citrate.

Too much citrate can hurt us. Citrate is

the raw material for fat molecules called triglycerides. Excess triglycerides

in the blood trigger cardiovascular disease, says Lustig. Some of the citrate

also stays as fat droplets in the liver; a fatty liver triggers insulin

resistance, which causes type 2 diabetes.

But it’s not just the citrate. Lustig says

that eating too much fructose can also spark inflammation in the liver, as well

as increase blood-pressure-raising byproducts like uric acid.

Overall, eating too much fructose from

added sugar is like using unleaded gasoline in a diesel engine: it makes bodies

sputter and cough till they seize in a puff of smoke.