Other epidemiological studies show a

relationship that’s tenuous at best between fructose and metabolic syndrome.

The Women’s Health Study found that risk of diabetes was no different in women

who consumed the lowest amount of sucrose (about 6 1/2 teaspoons) versus those

who consumed the most (about 14 teaspoons); the amount of fructose made no

difference either. A 2010 scientific paper that reviewed all the

epidemiological studies that have been published on the topic stated it like

this: “epidemiological studies, at this stage, provide an incomplete, sometimes

discordant appraisal of the relationship between fructose or sugar intake and

metabolic/cardiovascular diseases.” In addition, short-term lab studies

conducted in people in which they are plucked from their daily lives and placed

in a lab for a period of time show that when we cat a very large percentage of

our calories from pure fructose, we do have more triglycerides in our blood and

more fat deposits in our liver and muscle, but our blood pressure and body

weight don’t rise compared to people who eat the same percentage of their

calories from another carbohydrate. Though the trials are small (a dozen or two

participants), they are the best we have right now.

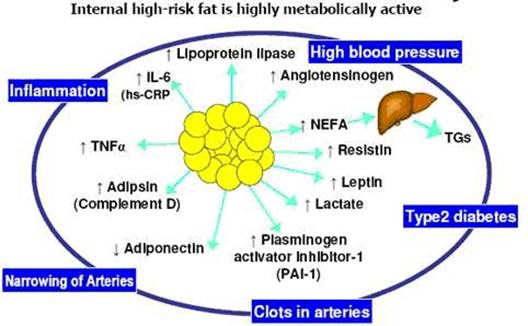

Type

2 Diabetes is not just about high sugar (glucose) but more about

hyperinsulinemia, inflammation and adipocyte dysfunction

In other words, these studies provide no

clear answer yet to the question of whether fructose in added sugar is giving

us metabolic syndrome.

Are We Overdosing?

Luckily for Lustig, Kimber Stanhope, Ph.D.,

and Peter Havel, D.V.M, Ph.D., have been busily conducting trials in their labs

at the University of California, Davis. In one of their studies, overweight or

obese people who spent 10 weeks drinking 25 percent of their calories from

fructose drinks (versus a group drinking glucose) increased their post-meal

triglycerides (a risk factor for heart disease) and decreased insulin

sensitivity (a risk factor for type 2 diabetes).

Interestingly, they also found that

drinking fructose caused the subjects to gain visceral fat, the kind of fat in

the belly that’s associated with metabolic syndrome; drinking glucose added

fat, too, but here the fat was subcutaneous, the “safe” kind that has no

established relationship with disease. Drinking fructose also enhanced the

body’s ability to convert carbohydrate into fat in the liver, which causes

insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes.

Stanhope is in the middle of another big

new trial in which, instead of giving subjects pure fructose (something no one

drinks in the real world) as she has in earlier studies, she is giving folks

what they can buy from convenience stores and vending machines: HFCS-sweetened

drinks. She’s also studying young, healthy people instead of obese people. The

trial’s first results (there’s more to come) were just published and they, too,

seem to support Lustig’s theory: triglycerides and “bad” LDL cholesterol

increased only in subjects who drank the fructose or HFCS, not glucose.

What's

good? What's bad? How much sugar is too much?

Still, the fructose doses used in most of

Stanhope’s studies are higher than most humans would normally consume. There’s

“no unequivocal evidence that fructose intake at moderate doses is directly related

with adverse metabolic effects,” said Luc Tappy, M.D., professor of physiology

at the University of Lausanne and one of the world’s premier fructose

researchers, in a review. But Lustig thinks the higher doses in many of these

trials just speeds up the inevitable. “It’s completely dosage dependent. A

little is fine. A lot is not. And that’s true of every poison,” says Lustig.

Many scientists, however, think that

focusing public health on one vilified nutrient is the wrong tack to take. Such

a strategy has backfired before: for example, doctors once told us all fat is

bad, so manufacturers took it out of processed foods (and, interestingly,

replaced it with sugar). Today, its recommended we eat 20 to 35 percent of

calories from fat most of which should be the healthy, unsaturated kind.

“We certainly agree we should eat less

sugar, but I think he’s making a huge mistake from apublic health perspective,”

says Katz. “We spent the last three decades doing exactly this: we thought just

oat bran is good for us, so we put it in everything. Then we just needed to cut

fat. Then it was carbs. So I can imagine we’ll soon have a vast proliferation

of sugar- or fructose-reduced junk food filled with some unhealthy

substitute... I can’t help but roll my eyes and ask, how many times do we have

to get this wrong before we get it?”

And Tappy is concerned Lustig’s public

message is leaping ahead of the science: “So far, except for triglycerides, the

data in the literature linking metabolic syndrome to fructose is pretty weak.”

But Lustig counters that, with the U.S.

losing $65 billion in worker productivity and spending $150 billion on medical

care for health problems associated with metabolic syndrome each year, “Do we

have to wait for those studies to be finished in humans before we can do

anything about it? I would suggest that that would be way too late.”

with

the U.S. losing $65 billion in worker productivity and spending $150 billion on

medical care for health problems associated with metabolic syndrome each year

At the end of his YouTube lecture that

sparked the sugar firestorm, the camera switches from generic blue PowerPoint

slides to a gray-haired, gray-suited Robert Lustig. After 90 minutes of

science, Lustig gives the audience some advice: drink only water or milk;

exercise; eat your carbs with fiber (fruit’s fiber slows the absorption of

fructose so it never overwhelms your liver: “When God made the poison he

packaged it with the antidote,” says Lustig); wait 20 minutes before your

second portion; use computers and TV for only as long as you exercise each day.

It’s all we need to avoid a deadly fructose fate, he says.

At the very end of his lecture, Lustig

peers at his captive audience. He pauses a moment, and makes his final appeal.

“I’m standing here today to recruit you in the war against bad food,” he says.

“And this [added sugar] is what’s bad.”

The storyteller closes his book. It’s up to

us to write the final chapter.