It’s Father’s Day this month, but what does it feel like when

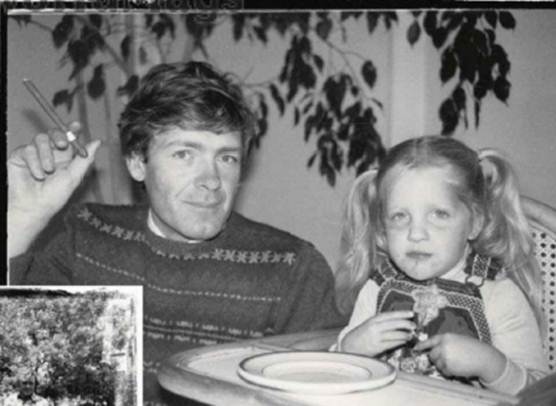

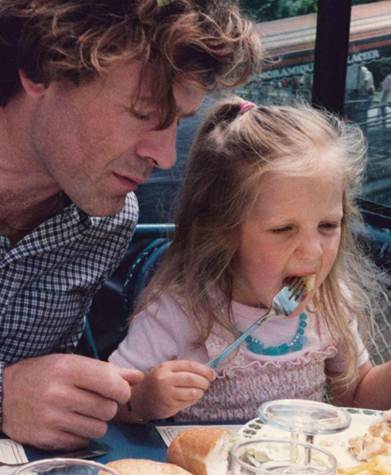

you don’t have one? Rachel Sullivan (below) reflects on how the loss of hers

has echoed throughout her life

One bright September morning over breakfast, my father told

me a joke I would remember for the rest of my life. I was nine years old, my

brother was ten, and nothing seemed to mark that days out as unusual or

different from any other. My mother, a teacher, was finding socks for my

brother’s PE kit, while my father sat at the Formica kitchen table, cutting

pictures of ice skaters out of magazines for my craft project. “Okay”, he said.

“I bet you 20p that you can’t work out the answer to this. What’s the only

thing worse than biting into an apple and finding a worm?” Matthew and I

started silently at each other for a minute or two before admitting defeat.

“Biting into an apple and finding half a worm”. “Grosssss!” we shrieked

in unison, before rushing out into the daylight to catch the bus that would

take us to school, friends, lessons, life.

Rachel Sullivan

And that was the last time I saw my father. Because later

that day, at the age of 36 – a year younger than I am now – he went up to the

loft of our three- bedroom Victorian house in a nice part of Surrey, and hanged

himself from a beam in the roof. This June will mark the 28th Father’s Day I

have lived through since then – every one spent avoiding greeting cards shops

and trying not to imagine a different version of my own life – and by now, I’ve

got pretty accustomed to being a celebration in which I will always be an

outsider.

Rachel Sullivan

and her father

That day, as my brother walked and I skipped home down the

road from the bus stop after school, we realised something was wrong. There was

an ambulance outside our house, sirens blazing, neighbours peering out of

windows. And there was our mother, ducking under the yellow tape around our

gate, behaving strangely, not like herself at all, telling us in an odd voice

to go round to a friend’s house and that she would pick us up – later.

Part of me still wishes time could have frozen in that

moment; before Later, before the conversation where she told us that Daddy

loved us, but he couldn’t tell us so himself because he was in heaven; because

Daddy was dead. And that even though he had really loved us, he had done it to

himself, by putting something around his neck, that stopped him breathing, but

it didn’t mean he didn’t love us, and we must always remember that.

Why he did it, I still don’t understand. He had recently

quit his job as a middle-school teacher and my mother said afterwards that she

had known for months that something was deeply wrong: he hadn’t been sleeping,

was saying strange things, became manically fixated on his Catholic faith. She

took him to see the priest, the family doctor; both said he was fine. He

probably just needed a holiday. But he wasn’t fine – he was suffering from some

undiagnosed form of depression, or anxiety, or both; no one really knows. These

days, we are all very well versed in the language of mental illness: there’s no

shame in shrinks, self-help books, Prozac. But for my father, all this came too

late.

I see that now, but as a nine-year-old, I wasn’t capable of

making sense of long division, let alone making sense of what he did that

afternoon. No one wants to watch a child grieve – surely, there couldn’t be

anything more heartbreaking for an adult – and no one truly encouraged me to

express how I felt. Instead, there were endless question. Do you want a bar of

chocolate? Do you want to go and watch the penguins at the zoo? Do you want to

see Daddy’s body before they bury him? That was an easy one to answer,

at least. I couldn’t think of anything worse. Still can’t.

We went to the

grave a lot to start with, but I always hated it. Because, especially to a

child, a cemetery is a cold, frightening place, full of grief and tragedy

Not long after that, I remember simply shutting down;

stopping feeling anything. At my father’s funeral, packed full of confused

children and weeping grown-ups, I started to cry, too. “Don’t cry here, in

front of everyone,” my mother said to me, gripping my hand so hard I thought

the bones might break. “We’ll all cry together when we get home – just the

three of us.” But of course, we never did. Instead, we did what we were quickly

learning would hurt the least and discussed something practical: what we should

write on Daddy’s headstone. What flowers we should plant. I never did ask my

mother why she told me not to cry that day. My best guess is that she was only

just holding it together and feared that this might have sent her over the

edge.

We went to the grave a lot to start with, but I always hated

it. Because, especially to a child, a cemetery is a cold, frightening place,

full of grief and tragedy. It doesn’t matter how much you sit there and talk to

that uneven mound of earth, or cry, or strike bargains with God; even if you

manage to feel, just for a second, like that person is with you, the truth is,

they’re not. Sooner or later, the sun goes down or your parking runs out or

you’re going to be late for dinner – you have to leave them behind.

Because they are dead and you are not, and you have to find

a way of going on living. And, gradually you do – you think about them less and

less, and sometimes not at all, and you become interested in boys, and watching

gymnastics, and books by Evelyn Waugh, and a million easier distractions. And

that’s when you really leave them behind: that gravestone starts to feel

like a measurement of the dying away of your grief. Your weekly trips to the

cemetery happen less and less often, until they become just a twice-yearly

pilgrimage of guilt where you clear away a bunch of dead flowers you’ve never

seen before and you wonder who else, after all this time, could still be coming

to see your father? And then you check your watch, even though you

haven’t really got anywhere else to be, and you shiver, wrap your coat more

tightly around yourself, and head for home, headphones in, music turned up

full. And even though it makes you feel desperately empty, you know this is

progress.

Many coping strategies got me through that time, most of

which won’t surprise anyone who’s on first-name terms with grief. Fantasising

was my chief drug of choice. I was constantly lost in elaborate scenarios based

around one thing: that my father was actually alive and the whole silly

business of pretending he was dead had been necessary for some perfectly

explicable reason. My favourite: that he was a member of the IRA (in my

defence, I didn’t really understand who they were) who was on the run from some

faceless villain – and all this, the police, the funeral, everything, had been

the only way of ensuring his safety. There were a thousand other variations on

this story, but I’m sure you can imagine how they all ended: the tears

streaming down my father’s face, my mother rushing towards him with open arms,

him enveloping me in a hug so big, it would make all the bad things go away.

I was constantly

lost in elaborate scenarios based around one thing: that my father was actually

alive and the whole silly business of pretending he was dead had been necessary

for some perfectly explicable reason.

The other coping strategy I found useful was lying. It was

almost impossible to speak the sentence, “Daddy committed suicide,” so I just –

stopped. Instead, I’d make something up, a heart attack, a bicycle accident,

maybe even a weird cancer – anything that seemed a little less shocking, a

little more palatable, less likely to offend. Kids can be brutal, and they spot

someone ‘different’ a mile off – with the dead father and the habit of starting

vacantly into the distance for long periods of time, I was at risk of sticking

out like a sore thumb. And I didn’t like that very much, so I started

pretending to be just like everyone else. I’d read the books they read and

laugh at the things they seemed to find funny. I never talked about my father

and I certainly never talking about my feelings.

What do you lose

when you lose your father?

So, what do you lose when you lose your father? First of

all, there are the practical things: someone who shows you how to change the

oil in your car, or helps you put up shelves in your first flat. And that’s a

surprisingly huge loss, which echoes throughout your life. But the emotional

stuff is harder to define. It’s difficult to analyse something you’ve never

really had, but I did sometimes look at my friends’ relationships with their

fathers and wonder what might have been. Mothers and daughters have close,

complex, occasionally competitive relationships, but what a daughter seems to

get from her father – which I guess I missed out on – is a kind of

unquestioning, uncomplicated adoration. My father used to tell me stupid jokes

and silly stories and I remember missing that very much. He would sometimes

swear at other drivers and make my brother and me giggle uncontrollably in the

back of the car, and I missed that, too. And when I had a nightmare, he would

come and sit with me, sometimes for hours, until I went back to sleep. When one

parent is gone, as a child, you feel terribly exposed. I used to worry for

hours about what would happen if my mother died, too, where Matthew and I would

live, and whether I would still be able to have my rabbit there.

“You carry that

frightened, betrayed and confused nine-year-old around with you forever”

I do know what it is to have a parent die in the normal run

of things, because I was unlucky enough to lose my mother to cancer when I was

32. And that was incredibly tough, and involved grieving, and I thought I’d

never feel like myself again, and then I did. But to lose a parent when you are

so young – so unable to react and process it – that’s another thing altogether.

Because if that happens, you carry that frightened, betrayed, confused,

disorientated nine-year-old around with you forever. She’s there when you can’t

sleep away from home because, for some reason, you feel scared; she’s there

when people ask how you are, and you say you’re fine, even though you’re

anything but; and she’s there when you fall in love repeatedly with men who you

know will let you down, just like he did.

And I did do all those things for a while. But not any more.

After my mother died, I found a great counsellor. It took time, and many tears,

and a lot of talking about things I’d tried hard to forget, but it really

helped. I think my story, in the end, is a positive one. When something like

this happens to you as a child, you have to fight hard to get back to where you

should have been, but I’m the living proof that it is possible. I’m getting

married this month to a man who loves me unconditionally. I struggle with the

notion of Happy Ever After – it’s been my experience that mean old life has a

callous habit of getting in the way of such a nice idea – but I’m Happy Right

Now, and that’s good enough. I have a career that fulfills me, a home, great

friends and a small, ridiculous dog who makes me laugh every day. Yes, loss

could still haunt my life, if I chose to let it, but most days – most days

– I manage to choose not to. I have friends who’ve also lost their fathers and

say they couldn’t bear the thought of a wedding: walking down the aisle without

the arm of the person they always imagined would be there. I understand that,

but I also don’t see why I should add to my life’s losses by not having the

big, warm, friend-filled, love-filled wedding I have always wanted. And the

hand I’ll be holding as I walk into my future will be that of the person who

shared that dreadful day back in 1983 with me – my brother. What happened to my

father, and therefore to us, was sad and tragic and difficult. But I can think

of something worse: for me to look back one day and realise I only lived half

the life I was meant to live.